Implementing SDGs in a Pre-sessional English Classroom

Rachel Hall Buck1, Jenifah Abu-Hassan2, Michelle Jimenez3 and Saif AlDarwish4

1 Rincon Research, Tucson, Arizona

2 Achievement Academy Bridge Program, American University of Sharjah, Sharjah, UAE

3 Instructional Designer, School of Business Administration, American University of Sharjah

4 Undergraduate Engineering Student, American University of Sharjah

Corresponding Author:

Jenifah Abu-Hassan, American University of Sharjah, Sharjah, UAE

Email: jhassan@aus.edu

The American University of Sharjah (AUS) presents an innovative case study in English language instruction that embeds the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in a pre-sessional English course, known as the Bridge program. The interdisciplinary initiative of implementing the SDGs was to equip students with linguistic competencies whilst also fostering global citizenship, irrespective of their future chosen career. The design includes active learning strategies, such as gamification and social media and engages students in problem solving tasks. The four-member design team comprised faculty with English as a second language and academic writing experience, an instructional designer, and a student representative who used their respective areas of expertise to develop the course. Assessment strategies cover both summative and formative evaluations to measure linguistic and sustainability competencies, aiming for transformative outcomes that extend beyond linguistic skills to include social responsibility and global awareness.

Keywords

education for sustainable development, learning design, English language learning, engineering education

Resumen

La Universidad Americana de Sharjah (AUS) presenta un innovador estudio de caso en la enseñanza del idioma inglés que incorpora los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible (ODS) de las Naciones Unidas en un curso de inglés pre-sesión, conocido como el programa Bridge. La iniciativa interdisciplinaria de implementar los ODS tenía como objetivo dotar a los estudiantes de competencias lingüísticas mientras fomentaba la ciudadanía global, independientemente de su futura carrera elegida. El diseño incluye estrategias de aprendizaje activo, como la gamificación y las redes sociales, y involucra a los estudiantes en tareas de resolución de problemas. El equipo de diseño, compuesto por cuatro miembros, estaba formado por profesores con el inglés como segundo idioma y experiencia en escritura académica, un diseñador instruccional y un representante estudiantil, quienes utilizaron sus respectivas áreas de experiencia para desarrollar el curso. Las estrategias de evaluación abarcan tanto evaluaciones sumativas como formativas para medir las competencias lingüísticas y de sostenibilidad, con el objetivo de lograr resultados transformadores que vayan más allá de las habilidades lingüísticas e incluyan la responsabilidad social y la conciencia global.

Palabras clave

educación para el desarrollo sostenible, diseño de aprendizaje, aprendizaje en inglés, educación de ingeniería

Part 1. The learning design

This case study is of a pre-sessional English course, known as the Bridge Program, at the American University of Sharjah (AUS). Students enrolled in the Achievement Academy Bridge Program courses are those whose English skills are not yet at the level of proficiency to be able to enroll on a university level course (e.g. as measured by IELTS or TOEFL scores).

Description and context

The students at AUS come from diverse international backgrounds and at a varied level of English language proficiency. In order to improve their English language skills, many enroll in the university’s pre-sessional English course called the Bridge Program. Pre-sessional English courses are common with international students in British higher education institutions as well as at international locations (Thorpe et al., 2017). The pre-sessional English course at AUS prepares students for their English for General Academic Purposes (EGAP) and English for Specific Purposes (ESP) courses that are required in later years.

Our aim was to embed SDGs in our pre-sessional English course in a way that would be relevant for all students irrespective of the degree subject they choose to follow afterwards. This also matched the strategic vision of AUS. Although we will focus here on engineering, despite the difference in intended career trajectories, every student should be thinking about their participation in the global community. Embedding education for sustainable development can also help our students develop ways to problem solve and be better equipped to enter global conversations with the necessary English language skills necessary to do so. Hence, we will focus on the interdisciplinary nature of engineering and provide a scenario where intercultural competence is needed.

Our Team

Each member of our team at AUS in the United Arab Emirates had specific expertise that contributed to implementing the UN’s SDGs and vision within a beginning language course. Jenifah Abu-Hassan had been teaching at the university’s Bridge Program for nearly 20 years and brought years of experience teaching English as a Second Language, including content relating to the different SDGs, long before the UNESCO published these. Dr. Rachel Hall Buck teaches academic writing and ESP courses in the English Department and offered expertise relating to language learning theories. Michelle Jimenez is an Instructional Design Assistant for the Center of Innovation in Teaching and Learning (CITL) with 16 years of experience in instructional design and e-learning. She inspires teachers at AUS to incorporate technological innovation, instructional pedagogies and best practices to enhance course delivery and instruction. Our team was completed with our undergraduate student Saif Abdulrahman AlDarwish, a first-year computer science major who offered valuable insights from a student perspective. Saif successfully had completed a pilot course implementing the SDGs in the Bridge Program and contributed his ideas about ways of assessing the learning outcomes and the modular design.

Student Learning Outcomes

Our team was excited about learning with the Learning Design and ESD Bootcamp (ALDESD, 2023; UNESCO IESALC, 2022; Toro-Troconis, Inzolia, & Ahmad, under review) experts, and hoped to learn more about developing and integrating learning outcomes with English language course outcomes. This meant that in our pre-sessional English course, we integrated ESD within the Student Learning Outcomes (SLOs); students will be able to:

· Complete a well-developed, organized and grammatically accurate written assignment.

· Conduct thoughtful analytical projects or presentations.

The rationale for this design is provided in the next section.

Rationale for the learning design

As foreign language teachers, we recognized the importance of using the SDGs in the classroom as a way “to elevate students’ environmental values, beliefs and norms through the use of Educational Sustainable Development (ESD) integration. Essentially, language support and meaningful content build on their existing values and knowledge when students enter a course” (Jodoin, 2020, p. 796). One example of such integration is a recent study of English language learners at Turkish and Russian higher education institutions where students were “interested in studying such topics as economic growth, full employment and decent work, access to justice for all, quality education and lifelong learning opportunities for all, ending poverty in all its forms, responsible consumption and production, climate change and its impacts” (Gunina et al., 2021, p. 10).

Beyond student engagement and interest, implementing SDGs in the foreign language classroom allows for the integration of cultural issues, specific vocabulary knowledge, and social practices with critical thinking and problem-solving tasks (de la Fuente, 2019; Jodoin, 2019; ter Horst & Pearce, 2010). Furthermore, “sustainability content provides opportunities for much needed, complex language production to reach advanced levels of proficiency” (de la Fuente, 2019, p. 134).

Using the UN’s SDGs also combined well with the Student Learning Outcomes related to language learning. The SDGs were used in conjunction with the AUS Student Learning Outcomes listed in the syllabus of “providing an engaging context to develop their English (reading, writing, listening, and speaking) skills. Students will be able to explore ways to develop grammar and vocabulary while learning about this specific interest area. They will be introduced to content-related materials through authentic experiences.”

Another design goal was to consider how ESD can transform the ways students communicate and speak. This can fall under the Social and Emotional Pillar of ESD, which “includes the social skills that enable students to collaborate, negotiate and communicate in order to promote the SDGs, as well as the skills, values, attitudes and incentives for self-reflection that allows them to develop” (CoDesigns ESD, 2021).

Further, integrating environmental goals with the language classroom can improve environmental literacy, promote “transformative and deeper learning” and support the transformation educational imperative of “care and conserve” rather than “compete and consume” (Sterling, 2015, p. 269). We agree with this statement, but also felt that assessing these goals can be a complicated endeavor, hence deciding to incorporate SDGs within the Student Learning Outcomes as described above.

Learning activities: achieving the specific learning outcomes

Supported by the expertise of our Instructional Designer, the learning outcomes were achieved through active learning techniques and incorporating technology such as the following:

- Use of interactive learning resources: The course utilized educational technology tools such as Nearpod which is an interactive platform that allows students to engage with course content in real-time. This platform allowed the instructional designer and the faculty teaching this course to create engaging presentations, quizzes, and other multimedia content, which help students stay engaged and focused during class.

2. Incorporation of gamification: Gamification was extensively incorporated in this course to make learning more engaging and fun for students. The instructional designer created quizzes, games, and other interactive activities that motivate students to participate and learn more. For example, the concept of “conformity” is a huge issue on social media that many young minds tend to follow blindly. According to Weismann (2022),

The digitally connected crowd, via social media, smart devices, and search engines, may greatly amplify this power of social conformity. Through the ever-increasing gaze of a pervasive audience online, we may become overly pressured, even coerced toward collective opinion, as social media’s mechanism of likes, dislikes, friends, and follows constantly subjects us to the crowd’s judgement along with that gaze. (p. 22)

By covering the topic of conformity, students learn to think critically rather than being mere followers of social media influencers being impacted by influencers sponsored ads, which are not always easily identifiable (Balaban, Mucundorfeanu, & Naderer, 2022). After watching short videos and reading articles on conformity, and after discussions, students are then engaged in Kahoot Quizzes where they are reminded about critical thinking (verify-verify-verify) and significant vocabulary words. Gamified quizzes are a fun way of helping students remember new English words and concepts they had discussed in class.

3. Use of social media: The instructional designer and faculty have also incorporated social media into the course design. Using platforms such as Twitter (now referred to as ‘X’) and Instagram, engage students and encourage them to participate in discussions related to the course content. This allows for increased collaboration and a deeper understanding of the material. For instance, the class watches a thought-provoking Instagram/YouTube/Twitter video (about 1 -2 minutes). After a short discussion (or no discussions at all), students focus on writing a response paragraph based on a few questions: e.g. How did the video make them feel? Do they agree/disagree with the points raised? What would they do differently? These videos could be about deforestation, mental health issues, women’s rights/opportunities, education, and other SDG topics.

- Creation of microlearning modules: The instructional designer created short, focused learning modules that were easy to digest and could be completed quickly. This helped students to learn on-the-go and allowed them to revisit specific topics when needed. At the beginning of the semester, students interviewed and photographed each other in an ice-breaker activity and then wrote a short blurb/caption about their new friend in an Instagram post (these posts are kept private for class viewing only). Later, they revisited this post in order to add which SDGs (a minimum of 3) their classmates would like to be active in at present and in the future.

5. Development of videos and other multimedia learning resources: The instructional designer developed instructional videos to capture students' attention and interest. These videos were visually stimulating, making it easier for students to understand and retain information. Videos also helped to break up the monotony of reading and writing, making learning a more dynamic and interactive experience. Students watched short movies on YouTube, for instance The Bitter Bond, an award-winning short film (2 minutes) about wild animals that are raised to only serve the needs of Big Game Hunters. With such videos, students learn empathy and to care for animals which is exactly what SDG Goal 15: Life On Land is all about.

- Integration of Technology: The instructional designer incorporated various technologies such as virtual reality, augmented reality, and video conferencing to make learning more interactive and immersive for the students. These technologies help to create a more dynamic and engaging learning experience for students.

Overall, the instructional designer implemented the use of innovative and creative instructional strategies which helped to create a more engaging and effective learning experience for the students. This in turn helped students more effectively engage in their language learning development and complete the assessments tasks.

Assessment of the specific learning outcomes

According to Gunina et al. (2021):

The aim of any course is to develop a set of competencies that will be useful for the learners when solving both professional and everyday problems. By integrating sustainability issues into the English language course teachers can help their students to acquire a number of competencies, such as anticipatory competency, collaboration competency, systems thinking competency, strategic competency, critical thinking competency, and self-awareness competency. (p. 8)

Throughout this case study, students were evaluated via formative assessments such as vocabulary tests, and summative assessments such as reflections at the end of units and at the end of the course. One of the challenges moving forward with this project is determining an effective way of assessing both the sustainability competences along with the learning outcomes of language development.

How the SDGs have been included

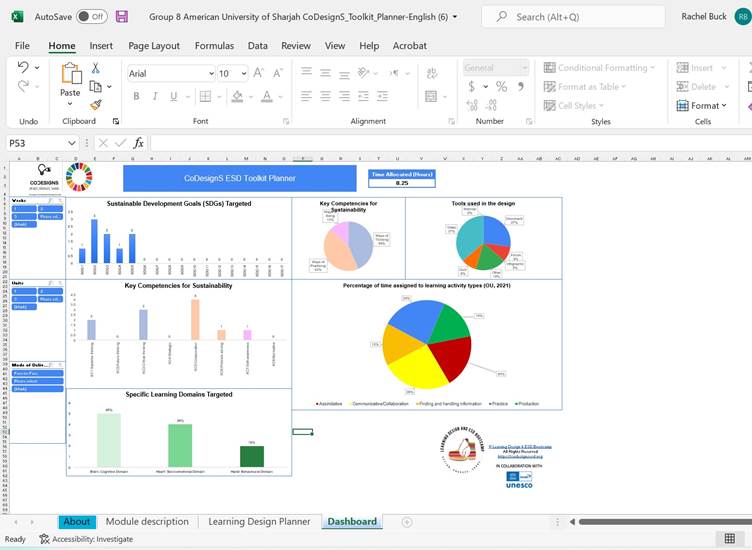

Using the CoDesignS ESD Toolkit (CoDesignS ESD, 2021; Ahmad et al., 2023) was admittedly a time-consuming process for us, but did allow us to see a larger picture of how the SDGs were incorporated into the pre-sessional English course. Figure 1 below shows the ESD Toolkit Dashboard, including percentages of each of the SDGs and the learning activities, the learning activity types and the tools used. The Co-DesignS ESD Toolkit allowed us to visually see the percentages of mapped hours. We mapped 8.25 learning hours via the Toolkit using the learning development resources discussed in Part 1 above.

Figure 1. Percentage of SDGs with learning activity types and tools used (CoDesigns ESD Toolkit, 2021)

Part 2. The process we used to arrive at the design

What worked well?

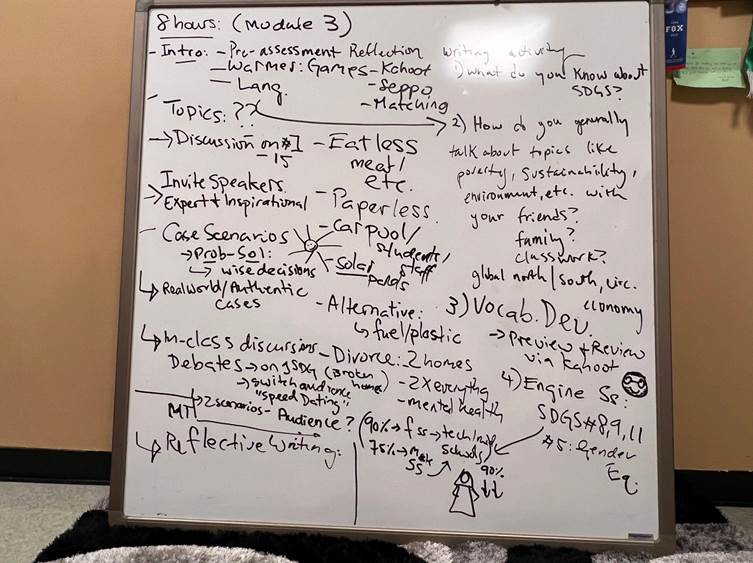

Meeting to brainstorm ideas was the most rewarding part of our design experience (see Figure 2). We discussed sustainability problems, including environmental, social, and political. Then we discussed how the SDGs could help combat those problems, and how incorporating the goals in the classroom could help students become problem-solvers. Combining the years of teaching experience that Jenifah and Rachel had along with the technological expertise that Michelle contributed together with Saif’s student viewpoint all helped us reach new ways of implementing the SDGs throughout the entire course.

Figure 2. Brainstorming session for sustainability topics from May 14, 2022.

We enjoyed learning about transformative pedagogical approaches during the Learning Design Bootcamp, which we could then contextualise for our AUS students. We came up with hypothetical situations based on what we imagined our students would need to know in the future (as engineers and other majors).

What were the challenges?

Using the Toolkit allowed us to think about how much technical knowledge or expertise undergraduate students needed in order to better understand the SDGs. Having recognized that embedding SDGs required a great deal of background knowledge on students’ part, we arrived at pedagogical approaches that were based on students’ language ability and their proficiency in disciplinary knowledge.

When our team met to brainstorm possible active-learning and student-centered activities, we came up against the issue that students did not feel connected to SDGs, because they did not see how global issues affected them at local level. In our first 8 hours of planning, we tackled this issue by first introducing the SDGs via multiple platforms and venues that showcase global problems. We then created activities and lessons that helped students understand how the issues affected them locally here in the UAE, as well as globally.

In our design, we created activities that developed students’ language skills by communicating as much as possible in class with class discussion (both small group and large class), having guest speakers, but also developed their written communication skills by producing written work in the form of reflections, surveys, short paragraphs, and subtitles for their videos.

Instead of designing one unit or activity that incorporates an SDG, we wanted to embed the SDGs throughout the entire course and briefly introduce the first 15 goals during the semester (rather than focusing on 1 or 2). Many of the key competencies that we are seeking to develop are about ways of thinking including systems thinking and critical thinking (CoDesignS ESD, 2021), however, we also recognize that many of the activities we planned cross the boundaries between the key competencies. The active-learning techniques used in the language classroom often involve ways of thinking, ways of practicing, and ways of being in the same activity, as keeping the boundaries between these competencies can be counter-productive when developing student-centered activities.

We also ran into a similar philosophical discussion when trying to decide what learning design activity types to plan in our design (assimilative, communicative, finding & handling information, productive, and practice, and assessment (CoDesignS ESD, 2021)). Many of these activities can overlap and students can accomplish all of them, or multiple, within the same activity. We were unsure if trying to focus each part of an activity on the specific framework type was beneficial or necessary in our language teaching context. For example, we planned a scavenger hunt around AUS campus using the Seppo platform. Students were put in groups to work collaboratively. Each task asked them to find an item/event that is related to one of the 17 SDGs. In the Toolkit, we decided that this particular activity could all fit into any from the Assimilative, Communicative, Finding and Handling, and Practice the Learning Design Activity Types which made it harder to categorize the activity.

Students are all very different and react to different activities in different ways. This is to be expected within classrooms of diverse student populations. We think that each activity in the ToolKit will have split amounts of time across the types of activity framework and suggest that educators using the ToolKit not get too rigid when categorizing each activity.

Saif’s reflection from a student perspective

As instructors, Jenifah, Rachel, and Michelle enjoyed the process of working directly with our undergraduate student, Saif. We have included below Saif’s reflection, as we believe that student voices in the designing process are important and too often overlooked:

I never thought of the future in terms of so many goals other than my own before such as graduating, getting a good job, getting married). With this Bootcamp, I know that as a future Engineer I need to make sure my work incorporates the SDGs. I will try to keep these goals in mind as I study and work. In fact, when I look at the Senior Design projects of my older peers in the College of Engineering, I am now aware of the SDGs that I need and would like to embed in my senior year projects.

As a Bridge student, I spent 2 semesters here before entering my degree program, I know how important it is to be exposed to new vocabulary and language concepts. However, having worked with my team, I now know the importance of SDG vocabulary and language concepts. For example, I learnt the difference between equity & equality, or the meaning of poverty, consumption, and infrastructure, and language such as raising-awareness, green-washing, climate-action, and circular economy.

As I worked with my team, I have become aware that I am learning much much more than just the English language. For instance, we looked at “Sky Runner” in one of the textbook units. It is the story of a girl, Mira Rai, from Nepal who stopped schooling at 12 to help her family - she used to go up and down the mountains carrying water and wood. Later she literally ran into Trail Runners and was introduced to this sport, and very soon after, she excelled in Trail running and became a World-famous competitor. I learned that many girls around the world lack opportunities that were only given to their male counterparts, and that girls’ education can be cut short due to family commitments. Here in the UAE, I am used to seeing women in all my AUS classes. However, I am now aware that not all families or communities, and even countries, give girls and women the same educational opportunities as they do with their boys and men.

After that article, we worked on another Active Learning task. We watched a video on Katherine Switzer who became the first woman to run and finish the Boston Marathon in 1967. For 70 years, only men had been allowed to run. People had very archaic ideas that women who participated in sports would become masculine, but after many push backs and challenges Katherine became an advocate for women in sports. In fact, because of her, women were allowed to enter the Boston Marathon five years later in 1972, and she also contributed to Women’s Marathon being recognized as an event in the 1984 Olympics - 90 years after men’s. Having done these two tasks out of many with my team; reading about Mira Rai, and watching the video on Katherine Switzer, I developed a more critical understanding of the importance of SDG #4 (Quality Education) and #5 (Gender Equality).

Conclusion

Working as a team helped us all better understand the importance of ESD, but also the challenges that come with implementing multiple goals into any classroom. As we continue to explore possibilities of ESD, we also keep in mind ways to formally and informally assess language learning goals along with SDGs in categories that reflect what happens in students’ minds and hearts.

In Saif’s words:

Working with my team has woken me up to all the possibilities and lack of possibilities in the world. I am the only male team member, and Dr. Rachel, Ms. Jen, and Ms, Michelle have shown me that women are intelligent, strong, tenacious, and funny! Every meeting we had was fun! I really hope that as I find my way through life and college that I can become an agent of positive change and inclusivity. I hope the tasks we work on will benefit Bridge and first year students.

For those wanting to incorporate the SDGs into the language learning curriculum, we encourage you to make the goal to increase students’ critical thinking, problem solving, and language learning skills via topics of conversations, lesson plans, and activities.

References

Ahmad, N., Toro-Troconis, M., Ibahrine, M., Armour, R., Tait, V., Reedy, K., Malevicius, R., Dale, V., Tasler, N., & Inzolia Y. (2023). CoDesignS Education for Sustainable Development: A Framework for Embedding Education for Sustainable Development in Curriculum Design. Sustainability, 15(23), 16460. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152316460

ALDESD (2023). Learning design and ESD bootcamp. https://aldesd.org/bootcamp-2023/

Balaban, D. C., Mucundorfeanu, M., & Naderer, B. (2022). The role of trustworthiness in social media influencer advertising: Investigating users’ appreciation of advertising transparency and its effects. Communications, 47(3), pp. 395-421. https://doi.org/10.1515/commun-2020-0053

CoDesignS ESD (2021). CoDesignS ESD framework and toolkit. https://codesignsesd.org/

de la Fuente, M. (2019). Stepping out of the language box: College Spanish and sustainability. In C. A. Melin (Ed.), Foreign language teaching and the environment: Theory, curricula, institutional structures (pp. 130–145). Modern Language Association.

Gunina, N., Mordovina, T., & Shelenkova, I. (2021). Integrating sustainability issues into English language courses at university. E3S Web of Conferences, 295. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202129505006

Jodoin, J. J. (2020). Promoting language education for sustainable development: A program effects case study in Japanese higher education. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 21(4), 779-798. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-09-2019-0258

Ter Horst, E. E., & Pearce, J. M. (2010). Foreign languages and sustainability: Addressing the connections, communities, and comparison standards in higher education. Instructional Approaches from Methods to Input, Output, Proficiency, and Standards, 43(3), 365-383. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2010.01088.x

Thorpe, A., Snell, M., Davey-Evans, S., & Talman, R. (2017). Improving the academic performance of non-native English-speaking students: The contributions of pre-sessional English language programmes. Higher Education Quarterly, 71(1), 5-32. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12109

Toro-Troconis, M., Inzolia, Y., & Ahmad, N. (2023), Exploring attitudes towards embedding Education for Sustainable Development in curriculum design. International Journal of Higher Education, 12(4), 42-54. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v12n4p42

UNESCO IESALC (2022, July 1). Bootcamp de Educación para el Desarrollo Sostenible formó a equipos de 21 universidades en pedagogías transformadoras para incluir ODS en los currículos. UNESCO IESALC Blog. https://www.iesalc.unesco.org/2022/07/01/bootcamp-de-educacion-para-el-desarrollo-sostenible-formo-a-equipos-de-21-universidades-en-pedagogias-transformadoras-para-incluir-ods-en-los-curriculos/

Vasseur, R., & Sepúlveda, Y. (2019). Beyond the language requirement: Implementing sustainability-based FL education in the Spanish foundations program. In de la Fuente, M. J. (Ed.), Language learning: Content-based instruction in college-level curricula (pp. 105-123). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003080183-9

Weismann, J. (2022). The crowdsourced Panopticon: Conformity and control on social media. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.