Evaluation for all? Why evaluation within and beyond higher education should be universal and accessible

Liz Austen1 and Stella Jones-Devitt2

1 Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield, UK

2 Staffordshire University, Stoke-on-Trent, UK

Abstract

This article discusses some of the challenges of current evaluation work in higher education (HE). Despite years of interest in this space, the sector is still struggling to capture what is working to enhance student outcomes. Our own recent work as evaluators for QAA Scotland’s Enhancement Themes seeks to address this impasse. This article will provide an overview of the Enhancement Themes work in Scotland and how evaluation is being re-positioned as the crux of activity within higher education institutions wishing to demonstrate effectiveness. A case study will be presented which illustrates how this could be achieved by describing the ongoing creation and piloting of a ‘Universal Evaluation Framework’ which aims to liberate colleagues from their fears around evaluation capabilities. The intended outcomes of use include the development of evaluation capabilities, increased confidence in evaluating change in HE spaces, and an evidence base for decision making regarding student outcomes. The interactive tool will enable colleagues to plan, design, implement and learn from their evaluations and record their reflections. Digital records extend this learning into publication, possible scholarship and, more tellingly, as evidence.

This case study outlines a potentially game changing tool which aims to engage colleagues and capture evidence of what works in an accessible and transparent way. In contrast to other approaches to evaluation capacity building in UK HE, this tool aims to support all, regardless of levels of evaluation experience, role, and starting points. Our framework will be universal and accessible, and intuitively and inclusively designed.

Keywords

evaluation, enhancement, impact, capacity building

Introduction

This article discusses some of the challenges of current evaluation work in higher education (HE) and how we, as responsible evaluators, have responded to them. Despite over 20 years of interest in this space, the sector is still struggling to measure, understand and untangle the evidence of what might be working to enhance student outcomes (Blake, 2022; Harrison & McCaig, 2017). Our own recent work as evaluators for Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) Scotland’s Enhancement Themes, a national programme of funded enhancement activity across Scotland’s higher education providers (HEPs), is used in this article as a case study to illustrate this point. This article will begin with an overview of the Enhancement Themes work in Scotland and will discuss how evaluation is being re-positioned as the crux of activity within Scottish higher education institutions (HEIs).

As evaluators, we are in the process of creating a digital ‘Universal Evaluation Framework’ (UEF) which aims to liberate colleagues from their fears around evaluation capabilities. The framework we propose creates a potentially game changing tool to engage colleagues and gather evidence of what works in an accessible way. In contrast to other approaches to evaluation capacity building in UK HE, we are designing a tool which aims to support all, regardless of levels of evaluation experience, role, and starting points. Our framework will be intuitively and inclusively designed.

The intended outcomes of use include the development of evaluation capabilities, increased confidence in evaluating change in HE spaces, and an evidence base for decision making regarding student outcomes. The interactive tool will enable colleagues to plan, design, implement, and learn from their evaluations, regardless of scale. In addition, the tool will capture personalised records of the phases of evaluation, which helps to extend this learning into publication and, more tellingly, as evidence. This is particularly important for the transparency of what is working, and what might not be working. We discuss our approach to design and implementation of the UEF below.

This article, and the tool it describes, encourages the publication of evaluation approaches and findings which would contribute to sector knowledge within the scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL) and beyond. SoTL has been specifically criticised for fostering reporting and publication bias, with a reliance on positive impact and success stories at the expense of lessons learnt or failures (Austen et al., 2021; Dawson & Dawson, 2018). The authors seek to champion a more transparent approach and draw on their work in Scotland as a specific case study which responds to, and challenges, these criticisms. The following discussion begins with an overview of the evaluation landscape in UK HE before presenting a case study of evaluation in Scotland and within the work of the QAA Enhancement Themes. An overview of the UEF will be provided alongside a rationale for its design and intended impact.

The evaluation landscape in UK higher education

For many years, the discourse of evaluation in UK HE has been dominated by debates around student feedback in course evaluation/the evaluation of teaching, and institutional metrics/performance, alongside reputational positioning. There were some evaluations of process and impact reported within the SoTL field (e.g., pedagogic action research) and more recently by academics evaluating in a widening participation (WP) context (e.g., widening participation and lifelong learning – Boliver et al., 2021; Foster & Francis, 2020; Jones & Masika, 2021). A more contemporary discussion of evaluation (in the last 10 years or less) has focused on programme evaluation – notably the formative and summative evaluation of process and the causal impact of implementing a specific intervention or programme against associated outcomes (Hanson et al., 2022).

Why is evaluation important?

The days of doing something merely because it might be a good idea, which arguably prevailed until the 21st century, have been replaced with notions of effectiveness, value and outcomes. The long-term economic squeeze, introduction of a privatised and monetised HE sector, shift to meeting skills-gaps, along with students now experiencing loans at the point of contact, has resulted in a shift towards an increasing commodification of the HE experience with a concomitant swing to student-as-customer, rather than student-as-learner. Moreover, funding bodies now wish to see clear and measurable outcomes from providers. The Scottish Funding Council (SFC, n.d.-a) presently invests around £1.9 billion a year in Scotland's 19 universities and 26 colleges. Each provider has to set out in its outcome agreement (SFC, n.d.-b) what it plans to deliver within the funding round in return for funding. This is also aligned with Ministerial priorities and the SFC’s (n.d.-c) strategic framework. Likewise, the Office for Students (OfS, 2022b) is distributing £1.4 billion in non-capital grants to universities and colleges, with funding targeted to support high-cost subjects, student access and success, along with the growth and development of Level 6 degree apprenticeships, and incentives to encourage greater provision of Level 4 and 5 sub-degree qualifications. At the heart of this funding is a drive to evaluate effective and measurable learning. Regulatory expectations for reporting against measures of impact are also increasing across various domains – see teaching and learning and learning gain – Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF), quality and standards – B3 Conditions of Registration, and equality of opportunity Access and Participation Plans (APP). In a recent blog, John Blake (2022) the newly-appointed Director for Fair Access and Participation at OfS, highlights this approach:

At the OfS, we will continue championing evidence-based practice, for our own work, the work we fund, and the work we regulate. As we reform our approach to access and participation, we want to see more higher education providers developing and sharing high-quality evidence, and more practitioners plugged directly into useful and practical research to enhance their effectiveness. This will help ensure all those considering higher education get the best possible support, advice and intervention to achieve their aspirations.

There is a compelling rationale espoused concerning the moral imperative to bring social justice to the forefront of HE. Very few would disagree with notions of increased accessibility, more heterogeneous student populations and better life chances for an increasing array of graduates entering a competitive jobs market. Yet, the direction of travel for highly decontextualised student outcomes data, as recently advocated by OfS (2022a) in its recent consultation about student outcomes does the exact opposite. By providing a one-size-fits all mandate for closing what are being called ‘lower value courses’, due to non-achievement of such unsophisticated outcomes, many doors will be closed upon students from disadvantaged backgrounds. Criticisms of these ideas have come from the most surprising commentators:

Those voices who say that “lesser” universities don’t deserve to survive Covid are ignorant of the existential importance of these very universities to the often disadvantaged communities in which they are rooted. It would be like saying we should close down schools in the bottom third of the league tables. Yet it is those schools, again disproportionately in the most deprived areas, that are often adding the most value to their students, even if their terminal results are not stellar. (Anthony Seldon, outgoing VC of the private University of Buckinghamshire, 2020)

This demonstrates why the vast majority of respondents were not in favour of an approach that sets numerical baselines and assesses absolute performance as a way of achieving the OfS policy aims as reported by OfS (2022) in their analysis of responses to the consultation about regulating student outcomes. Hence, there has never been a more urgent need to develop assured mechanisms which evaluate the real effectiveness of provision in the sector as it comes under increased scrutiny of success offset against a neo-liberal value for money agenda. The recently launched evaluation manifesto assembled by the Evaluation Collective (2022) provides a riposte to this overly simplistic, and often punitive, mechanism which decouples context from outcomes. Its first principle defines evaluation as: “an approach which helps to understand and explore what works and doesn’t work in a given context and is of value to stakeholders. The aim of evaluation is actionable evidence-informed learning and continuous improvement of process and impact. We stand against the performative, task-focused, tick box evaluation machine, and define evaluation as a collective responsibility within organisations, focusing attention and effort on transformative educational outcomes” (Evaluation Collective, 2022). The work underpinning this UEF, and the accompanying pedagogic analysis, aligns with the latter approach in driving new ideas for evaluating effectiveness in HE.

There has been considerable learning from those who began evaluating in the access/outreach space (e.g., Crawford et. al., 2017), often through informal routes rather than publication. Evidence and evaluation of student success and progression interventions are increasing, propelled by a WP or Equality, Diversity and Inclusion agenda and high profile (high spend) initiatives, such as those funded to close the degree awarding gap and increase a sense of belonging (Mountford-Zimdars et al., 2015; Thomas, 2012). However, evaluation practices in this area do require more exploration and support. Austen (2021) and Austen et al. (2021) suggest that these evaluative practices which aim to enhance student success are often grounded in methods and data generation rather than evaluation and critical thinking, tend to be activity-led rather than outcome/theory-led, can be restricted by short time bound projects, are confused by competing agendas regulating quality processes and continuous improvement, tend to over report positive impact (as also seen in Dawson & Dawson, 2018) and are producing notable evidence gaps (for example, regarding progression).

One of the explanations for these evidence, capability and skills gaps is that the increased capacity building opportunities have not increased in line with the increases in expectations for evaluation; see Blake, 2022, above. The evaluation ‘ask’ is widening yet it is often a hidden resource. There is a variety of capacity building resources available to colleagues working across the student lifecycle in the UK. In Scotland, the Scottish Framework for Fair Access (n.d.) have an online toolkit and a community of practice (Scotland’s Community of Access and Participation Practitioners, SCAPP) which aims to present evidence of effective interventions and provide an evaluation guide to support evaluation practice. Following a similar format; in England, the Transforming Access and Student Outcomes (TASO, n.d.) What Works Centre provides online resources, training and funded support for HE evaluations which aim to produce causal evidence concerning the elimination of equality gaps in HE. Evaluation training that is not specific to HE is also available - Social Research Association (n.d), UK Evaluation Society (n.d), BetterEvaluation (n.d) – and some HE institutions share their approaches via open access (e.g., Sheffield Hallam University Student Engagement, Evaluation & Research, n.d). The accessibility, relevance and inclusive nature of these resources varies and leaves those who seek to evaluate to navigate a complex web of outputs; where should they start?

A finished and polished study of an approach to evaluation and evaluation capacity building will not be presented here; indeed, this is antithetical to our approach. Rather, this paper presents a case study of evaluation in Scotland and within the work of the QAA Enhancement Themes. This case study has been constructed mid-way through a funded contract and intends to provide formative reflections on what has been achieved, what has been learned thus far about our own practice as evaluators, and what is still to come. The discussion of the remaining work focuses on the piloting and testing of the digital UEF.

Case Study “Evaluation for all: The Scottish Enhancement Themes”

Evaluation brief, aims and outcomes

An enhancement-led approach is integral to the work of QAA Scotland. The national programme of Enhancement Themes “encourage institutions, staff and students to work together to develop new ideas and models for innovation in learning and teaching. Each Theme also allows the sector to share and learn from current and innovative national and international practice” (QAA Scotland, n.d.). The first Theme – ‘Assessment’ - began in 2003. The current Theme is ‘Resilient Learning Communities’ and runs from 2020-2023. From 2014, QAA Scotland included resourcing for independent evaluation of the impact of the Enhancement Themes. QAA Scotland formally contracts with each Scottish institution to deliver on a plan of work, and funding is released at key points during the year to support the delivery of these plans. As noted, a significant amount is invested across the sector, with £1.9bn being provided this year by the SFC.

The evaluation brief set by QAA Scotland in December 2020 was to evaluate the impact of the current Enhancement Theme (Resilient Learning Communities), alongside the impact of 20 years of the Enhancement Themes in Scotland. The co-evaluators proposed to intertwine these evaluations for maximum effect. The longitudinal nature of this evaluation is part retrospective (e.g., going back to early Enhancement Theme work from 2003-4 onwards which had minimal overt evaluation) alongside evaluating the present-day theme (Resilient Learning Communities) whilst also considering its’ future-proofing, too (juxtaposed with other themes emergent from the two decades of enhancement work). The sector-wide work within the Resilient Learning Communities theme is primarily focused on student learning experiences, success and long-term outcomes of student retention and attainment and the institutional cultures in which student success is mobilised.

The aim of this evaluation work is to:

· identify the impact of the theme activity on the student experience so that, at the end of the theme, it is possible to identify the ways in which the student experience has been improved, as well as the enhancements to policy and practice.

The objectives of this work are to:

· develop or adapt a framework/approach/model, in consultation with the sector, that will measure the impact of the current and previous themes on the student experience, and which is capable of capturing activity within institutions as well as at sector level;

· use the framework to measure and report on the impact of the theme and related activity;

· use the framework to measure impact on a longitudinal basis so that learning from activities can be shared on an ongoing basis; and

· identify how the framework could be used or modified to measure the impact of future Enhancement Themes.

To meet these aims and objectives, the evaluation consists of four phases. Phase 1, crucially, focused on building relationships, immersion into the Enhancement Theme context and providing advice, guidance, and skills development through capacity building. Whilst there was some front loading of this component, it continues through all phases of the evaluation to maintain currency, authenticity and buy in. Phase 2 concerned data gathering, Phase 3 testing and refining of key themes and Phase 4 reporting and piloting of outputs, including the UEF. Several of these phases have not been realised in a linear fashion but exist simultaneously as aspects of the evaluators work. With relevance to this article, this evaluation intends to present both successes and lessons learnt of the Enhancement Themes activity and encourages colleagues in Scottish institutions to do the same through capacity building and the creation of a tool for recording evaluative decisions. Each phase of this work will now be outlined in the methodology before discussing the relevant outputs, emerging findings, and next steps.

Methodology

Phase 1: Building relationships and designing success is crucial

Our evaluation work is underpinned by a collaborative ethos. This is the way we work and – most importantly – it has been seen to work effectively, characterised by an inclusive, heterogenous approach, as reflected our previous collaborative approaches. Ownership is crucial, including developing appropriate capacity-building and designing inclusive evidence-gathering from the outset. Proportionality is important, too, involving designing evaluation processes that work effectively using available resources in a realistic manner. It is also about discussing possible counterfactual impacts of the work (i.e., has the series of themes made any difference, or would impact have occurred, regardless?). As relatively impartial evaluators, we began to facilitate those critical conversations from January 2021.

The absolute necessity for engagement of sector participants in this work has been paramount and during inception an Expert Reference Group was constructed for this project. The co-evaluators had already built some excellent working relationships in the Scottish sector due to work done in developing the recent Guides to Using Evidence, (Austen & Jones-Devitt, 2019, 2020) and this engagement was extended to key Enhancement Theme stakeholders, including the SFC and international colleagues with an interest in evaluation. The use of an Expert Reference Group applies an integrative review methodology (see Jones-Devitt et al., 2017) as a key engagement process. This process recognises that, whilst synthesised evidence can be classed as ‘real’ (in this case, evidence of ‘what works’ in evaluation research), the collation of expert opinion as evidence, per se, is vital in developing understanding of emerging concepts which can then be explored and further tested. Using an Expert Reference Group can also build ownership and reach to enable sector wide utilisation of the evidence base and the promotion and use of any outputs. We will also use the international expert group to help us sense-check proportionality throughout the process.

Phase 2 Gathering evidence

Documentary analysis provided an interesting starting point. End of theme reports and resources, project briefs, and institutional reports were analysed to identify emerging lines of inquiry. Attendance at key stakeholder meetings (Theme Leaders Group) became part of the evidence base aligned with the Integrative Review element. Gap-mapping, a method used to illustrate a visual overview of evaluation, was presented, graphically depicting types of interventions evaluated and outcomes reported.

A retrospective Theory of Change was also developed during this phase, co-designed by the evaluators using knowledge from documentary analysis and stakeholder meetings with theme leaders. This exploration of how enhancement changes were occurring provides the foundation for assessing the strength and contribution of impact claims. Phase 2 of the evaluation was completed in September 2022.

Phase 3: Emerging themes, testing, and steering

Phase 3 concerns gathering more evidence emerging from the current theme, aligned with findings of prior themes. Further evidence will be gleaned from Contribution Analysis (TASO, n.d.) which will pursue gaps already identified from the earlier mapping. and collate evidence to make inference regarding causality. This process helps to attribute a reasoned level of impact resulting from identified activities, especially where an evaluation might be incomplete, but the work has already finished. As an example, this analysis will explore the logical connection between sharing sector wide resources via Enhancement Theme activity and any associated impact on student experience and outcomes across the Scottish HE sector.

Phase 4: Framework piloting, people development, reporting, and sharing

During all previous phases of this evaluation of the QAA Enhancement Themes, the UEF is being continually developed. Data gathering assists further construction and testing of the UEF, and emerging insights are identified which will contribute to interim reporting. By phase 4, prototyping of a UEF, via existing theme application, gathers momentum. This helps develop UEF in advancing its repertoire of guided decision-making options, concerning:

· Scale and phase of intervention

· Requisite skills

· Appropriateness of theory of change model

· Whether future-facing or retrospective

The UEF will be animated by evidence-informed case studies to create further capacity-building opportunities to maximise utility. The global expert group will help drive dissemination networking opportunities, especially pertinent for international take-up and in exploiting reach and reputation of the QAA brand.

Output (Universal Evaluation Framework)

The development of the UEF and evaluation of previous and current QAA Enhancement Themes have been intertwined for maximum effect. The aim of the UEF, as a digital tool, is that anyone looking to evaluate impact in HE can use it, regardless of starting point AND regardless of previous experience of evaluation research. Indeed, the overarching utility of the proposed evaluation framework development has to withstand past, present and future facing project evaluations. Effective operationalisation of the UEF through application of present theme evaluation is critical. This accessible, ‘evaluation for all’ approach welcomes pedagogic researchers alongside WP practitioners and strategic leaders, enabling them to reflect on their work using an evaluative lens. We aim to create a tool which is universal and accessible to all, such that colleagues within any HE context can use it, including continued use for the QAA Enhancement Theme projects.

Therefore, the overarching aim of the co-evaluators is to construct an evaluation framework that is diagnostic from the outset to cover all eventualities. This means that any intervention, of any scale (and regardless of whether baseline evidence has been gathered) will be located on the framework and certain methods will be suggested as being the most effective way to capture evidence for that approach. There is an array of data collection tools (ranging from Random Control Trials, quasi and non-experimental through to qualitative), theories of change and predictive modelling approaches which need to be made available as part of an evaluation framework repertoire. Key factors in the success of any framework include being proportionate (see Parsons, 2017) so that the right amount of resource and effort is allocated for maximal impact; another factor relates to capacity-building so that practitioners can become more autonomous in making judicious choices and wise application.

UEF uses a set of diagnostic processes to guide:

· What evidence you need

· How to gather it

· How to analyse it

· How to do it proportionately with available resources

Creation of the UEF: Design, inception and proposed operationalisation

The UEF will be an interactive digital tool for those embarking on evaluation to learn, develop and record their decision making. As stated above, the UEF is designed to enable anyone, notwithstanding prior experience as an evaluator, to navigate, construct, and capture an appropriate evaluation process. This is regardless of starting point.

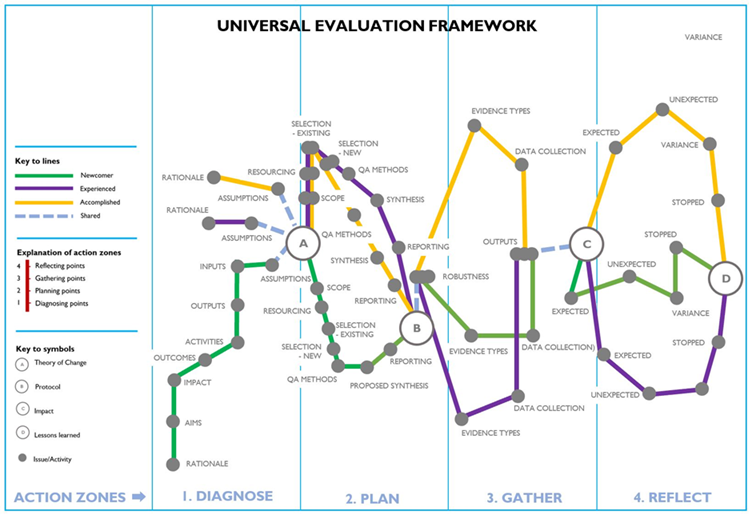

Design: The UEF prototype looks complex when all routes are shown but is really quite simple once the relevant level of experience is accessed by the end user. Figure 1 shows all users & all stages as a front-facing tool in its most complex form.

Figure 1. UEF map

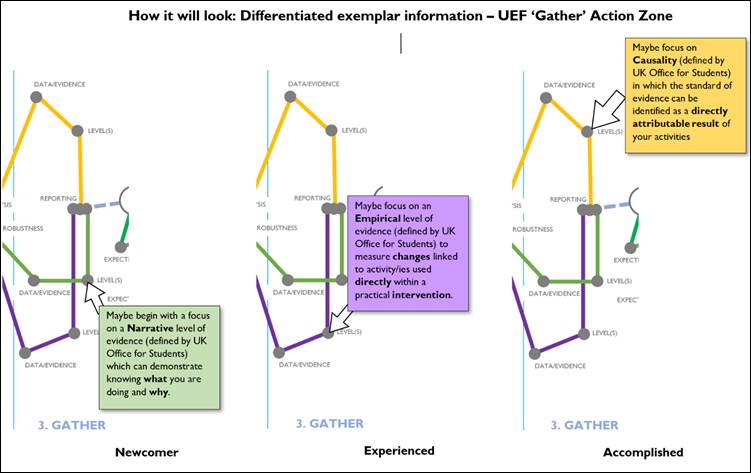

The UEF is designed so that a helpful descriptor is visible for each level of differentiated experience. Figure 2 highlights what occurs when each issue/activity point (small grey circle) is clicked in a relevant action zone. The exemplar below illustrates the difference for each route when clicking on level of evidence in the Gather Zone.

Figure 2. Visible information when activity/issue point is clicked

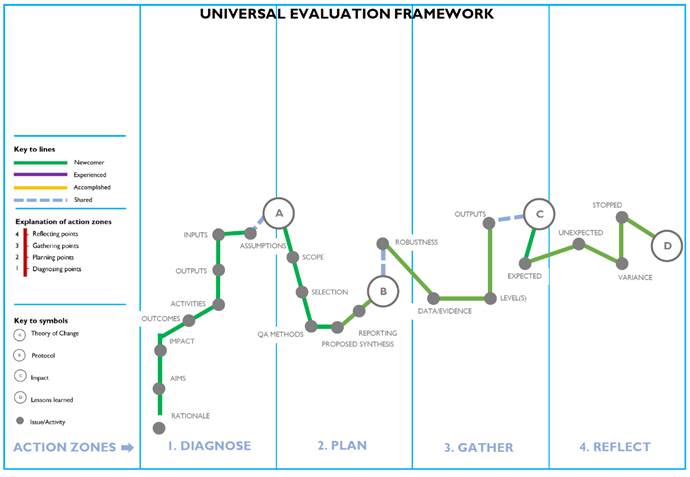

It is proposed that each level of experience can be made more visible by omitting other routes when in use. Figure 3 shows what the Newcomer route looks like, when accessed directly by the user.

Figure 3. Separated out ‘Newcomer’ UEF route exemplar

To succeed, the UEF will need to be easily accessed and intuitive for the end-user. It will also need to be easy to maintain and update when new evaluation ideas need to be added; hence, authoring should only need basic skills. The UEF will be able to store summary information provided by the end user, which will be done by inputting summary evidence at stages A) Theory of change, B) Protocol, C) Impact, and finally D) Lessons learned. It is imperative that this tool can create a summary that can be downloaded by the end user and shared with others in an accessible and stable format, such as a PDF. Moreover, the UEF is being designed so that it can link to wider resources which are not directly on the landing page, as this should be kept as a signposting/evidencing tool with simple, long shelf-life explanations of concepts at issue/activity points and Action Zone junctions so that it does not immediately date or be overly reliant upon continuous updating.

We believe that UEF can be a game-changer in the sector due to its open access nature and applicability to a wide range of staff and HE contexts. This tool will be sustainable, with the ability to be used successfully by all interested in designing effective evaluation processes AND supplemented by exemplar case studies. We envisage that the UEF will be in demand across the sector as something many can use confidently, regardless of initial skills. This framework aims to disrupt the boundaries of what we think we know constitutes a great student experience. Once confidence is built, the reporting of evaluative findings will increase, and will include, through supported collaboration and publication of evaluation planning, a transparency in what works, and what doesn’t work, in the enhancement space. The tendency to bias reporting in solely highlighting positive outcomes will be replaced by publication for learning; therefore, providing enhancement in its truest form.

Emerging evaluation findings

Although we cannot disclose the knowledge content of our emerging QAA Enhancement Theme evaluation findings at this stage, we can share that we will be reporting upon a plethora of outputs and knowledge, gleaned from evaluation of two decades of evidence from QAA Enhancement work. We hope that this longitudinal evaluation will demonstrate what works and why, conduits of success, and things deemed less effective. We are able to share some of our lines of enquiry, that we are reporting against and have been instrumental in shaping the design of the UEF. Through undertaking documentary analysis and gap mapping, alongside perusal of annual reporting of recent theme work concerning Developing Resilient Communities, five key areas emerged, comprising theme engagement and management, modelling of evidence and impact measures, methodological guidance, capacity-building of evaluative mindsets, and future-proofing. Information in these documents were analysed via a systematic evaluation extraction pro-forma after which the evaluators independently analysed the emerging lines and triangulated these ideas accordingly. These ideas have now been translated, by means of speculative but reasoned hypothesis, into workable lines of enquiry we are pursuing. To facilitate wider discussion, these lines have been turned into broad based questions with supplementary areas to explore.

Next steps

This case study has presented an overview of the work of evaluators to explore previous and current impact of the QAA Enhancement Themes. The detailed focus on outputs, specifically the UEF serves as a preview for the publication of findings in July 2023.

Emerging findings are driving the development of the UEF. The feedback from our Expert Reference Group and colleagues within QAA Scotland have been positive and supportive of this endeavour. As indicated above, we are building a UEF tool which will hopefully be used open access and evaluated accordingly. The early piloting will be accomplished by using and evaluating UEF scaled pilots throughout the QAA Scotland networks, with the hope of finalising the tool for wider sector uptake around six months thereafter. We are in the process of designing an accompanying staff development programme for UEF to scaffold the learning of those volunteer institutions. We envisage this will be light touch, as the front-loaded design phase of UEF will be developed to foster intuitive use premised on inclusive pedagogy. Findings from the longitudinal evaluation will be shared in summer 2023, alongside launch events for the UEF shortly thereafter. As responsible evaluators, we anticipate that the UEF will provide both a legacy and a pragmatic, utilitarian response to learning which has been captured throughout the process. The publication of this case study goes some way to achieving this.

Conclusion

The world of evaluation research often collides with, instead of complementing, pedagogic practice. We propose that pedagogic evaluation research should provide a space in which to co-exist effectively and constructively. The move to make evaluation even more specialist and ‘expert’ goes against notions of empowerment: surely, the people who are at the heart of great learning, including our students, know what effectiveness looks like? We just need to tease it out. Good evaluation processes, alongside confidence and capacity building, can assist the design and capture of such effectiveness. The Universal valuation ramework seeks to do precisely that; by demystifying evaluation into a set of signposted and reflexive processes (see Figures 1, 2, and 3) which all can use. In doing so, we facilitate the recognition of the ‘evaluative mindset’ in which all practitioners become thoughtful evaluators of their own practice, translating this into effective evidence-informed curriculum design processes alongside recognising the sovereignty of outcomes rather than activities. This paper and the systematic approach to capturing meaningful evidence described herein as fundamental to the UEF, provides a riposte to notions that capturing what works, what doesn’t and why can feel too onerous – or even meaningless – for those seeking to evaluate in this space.

This article aims to critically and intellectually engage with methodologies that support pedagogical evaluation. We hope that the work described thus far to underpin the process of longitudinal evaluation of the Scottish Enhancement Themes will give others the confidence to share their ideas about effective learning in HE. Furthermore, in the UEF, we have developed a highly pragmatic response to addressing some of the barriers occurring for bringing together evaluation and SoTL practice into one space: namely through what we call effective Pedagogic Evaluation Research. This work draws upon notions of SoTL, as defined by Potter and Kustra, 2011, concerning being systematically studious in developing insights and understanding to maximise learning, then shared with others for effective critique. When fused with effective evaluation, which is not only retrospective but future-facing, potential benefits for learners and the sector are accelerated. The work described here, and the emergence of the UEF as a productive and reusable outcome of such learning, is testament to the power of such fusion.

This article has provided an overview of the current evaluation landscape in UK HE and a case study example of the Enhancement Themes work in Scotland and how evaluation is being re-positioned as the crux of activity within HEIs. It uses this case study to highlight a commitment to evaluation and the benefits it can bring to the scholarship of teaching and learning and enhancing student outcomes. The driving principle of the authors is one of capacity building and empowerment. The design and creation of the UEF will serve as a legacy tool from this work described in this case study. This article aimed to provide a rationale for development whilst raising awareness and interest from the sector.

References

Austen, L., & Jones-Devitt, S. (2019). Student guide to using evidence in higher education. QAA Scotland Enhancement Themes. https://www.enhancementthemes.ac.uk/current-enhancement-theme/student-engagement-and-demographics/students-using-evidence

Austen, L., & Jones-Devitt, S. (2020). Staff guide to using evidence in higher education. QAA Scotland Enhancement Themes. https://www.enhancementthemes.ac.uk/evidence-for-enhancement/optimising-existing-evidence/staff-guide-to-using-evidence

Austen, L. (2021). Supporting the evaluation of academic practices: Reflections for institutional change and professional development. Journal of Perspectives in Applied Academic Practice, 9(2), 3-6. https://doi.org/10.14297/jpaap.v9i2.470

Austen, Liz, Hodgson, R., Heaton, C., Pickering N., & Dickinson, J. (2021) Access, retention, attainment, progression – an integrative literature review. AdvanceHE. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/news-and-views/access-retention-attainment-progression-integrative-literature-review

Austen, L. (2022, April 29) Working together on access and participation evaluation. Wonkhe. https://wonkhe.com/blogs/working-together-to-take-evaluation-seriously/

BetterEvaluation. (n.d). Welcome to BetterEvaluation. https://www.betterevaluation.org/

Blake, J. (2022, March 10) Evaluation, evaluation, evaluation. Office for Students. https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/news-blog-and-events/blog/evaluation-evaluation-evaluation/

Boliver, V., Gorard, S., & Siddiqui, S. (2021). Using contextual data to widen access to higher education. Perspectives: Policy and Practice in Higher Education, 25(1), 7-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603108.2019.1678076

Crawford, C., Dytham, S. & Naylor, R. (2017). The evaluation of the impact of outreach proposed standards of evaluation practice and associated guidance. Office for Fair Access. https://pure.northampton.ac.uk/en/publications/the-evaluation-of-the-impact-of-outreach-standards-of-evaluation-

Curtis, H. L., Gabriel, L. C., Sahakian, M., & Cattacin, S. (2021). Practice-based program evaluation in higher education for sustainability: A student participatory approach. Sustainability, 13(19), 10816. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131910816

Dawson, P., & Dawson, S. L. (2018). Sharing successes and hiding failures: ‘Reporting bias’ in learning and teaching research. Studies in Higher Education, 43(8), 1405-1416. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1258052

Evaluation Collective. (2022) The evaluation manifesto. https://evaluationcollective.wordpress.com/evaluation-manifesto/

Foster, C., & Francis, P. (2020). A systematic review on the deployment and effectiveness of data analytics in higher education to improve student outcomes. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(6), 822-841. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1696945

Hanson, J. Brown, G, & Crockford, J. (2022). Theory of change as model building: Unedifying contexts and mechanisms as our focus for evaluation. In S. Dent, A. Mountford-Zimdars, & C. Burke (Eds), Theory of change: Debates and applications to access and participation in higher education (pp 35-56). Emerald. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-80071-787-920221003

Jones-Devitt, S., Austen, L., & Parkin, H. J. (2017). Integrative reviewing for exploring complex phenomena. Social Research Update. https://sru.soc.surrey.ac.uk/SRU66.pdf

Jones, J., & Masika, R., (2021). Appreciative inquiry as a developmental research approach for higher education pedagogy: space for the shadow. Higher Education Research & Development, 40(2), 279-292. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1750571

Harrison, N., & McCaig, C. (2017). Examining the epistemology of impact and success of educational interventions using a reflective case study of university bursaries. British Educational Research Journal, 43(2), 290-309. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3263

Mountford-Zimdars, A., Sabri, D., Moore, J., Sanders, J., Jones, S., & Higham, L. (2015). Causes of differences in student outcomes. HEFCE. https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/23653/1/HEFCE2015_diffout.pdf

Office for Students (Ofs). (2022a). Analysis of responses in relation to regulating student outcomes and setting numerical baselines. Office for Students. https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/media/7fe4b4c7-e51c-4be6-87fe-d31f87012ddd/analysis-of-responses-in-relation-to-regulating-student-outcomes-and-setting-numerical-baselines-2.pdf

Office for Students (OfSb). (2022, June 8). OfS announces £1.4 billion funding for higher education. https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/news-blog-and-events/press-and-media/ofs-announces-14-billion-funding-for-higher-education/#:~:text=The%20OfS%20will%20distribute%20%C2%A3,Level%204%20and%205%20qualifications

Parsons, D. (2017). Demystifying evaluation: Practical approaches for researchers and users. Bristol University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1t89h20

Potter, M. K., & Kustra, E. D. H. (2011). The Relationship between scholarly teaching and SoTL: Models, distinctions, and clarifications. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching & Learning, 5(1), Article 23. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2011.050123

Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) Scotland. (n.d.). About Enhancement Themes. QAA Scotland. https://www.enhancementthemes.ac.uk/about-enhancement-themes

Scottish Funding Council. (SFC). (n.d.-a). Universities and higher education institutions we fund. https://www.sfc.ac.uk/funding/universities-we-fund.aspx

Scottish Funding Council. (n.d.-b). Outcome agreements. Scottish Funding Council. https://www.sfc.ac.uk/funding/outcome-agreements/outcome-agreements.aspx

Scottish Funding Council. (n.d.-c). SFC strategic plan. Scottish Funding Council. https://www.sfc.ac.uk/about-sfc/strategic-plan/strategic-plan.aspx

Scottish Framework for Fair Access. (n.d.). The toolkit. Scottish Framework for Fair Access. https://www.fairaccess.scot/the-toolkit/

Seldon (2020, July 3). My biggest failure was being a v-c, but I don’t regret it. Times Higher Blog. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/blog/my-biggest-failure-was-being-v-c-i-dont-regret-it

Sheffield Hallam University Student Engagement, Evaluation & Research (STEER). (n.d.). Welcome to STEER. https://blog.shu.ac.uk/steer/

Social Research Association. (n.d.). https://the-sra.org.uk/

Thomas, L. (2012). Building student engagement and belonging in Higher Education at a time of change. What works? Student retention and success programme. Paul Hamlyn Foundation. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/building-student-engagement-and-belonging-higher-education-time-change-final-report

Transforming Access and Student Outcomes in Higher Education. (2022). Contribution analysis. https://taso.org.uk/evidence/evaluation-guidance-resources/impact-evaluation-with-small-cohorts/getting-started-with-a-small-n-evaluation/contribution-analysis/

UK Evaluation Society. (n.d.). https://www.evaluation.org.uk/