Identities of a post-graduate research student

Abbie Cairns1

Norwich University of the Arts, Norwich, UK

Abstract

This paper explores the multiple identities held and embodied by a post-graduate research (PGR) student and helps to produce new knowledge about the identity of PGR students. This could have wider implications for the sector by helping to facilitate an understanding of those studying within it.

The results are contextualised with literature from the field of art (Daichendt, 2010; Thornton, 2013), and the identities of the researcher are visualised on networks of enterprises. Networks of enterprises are visual tools for tracking and charting the different enterprises of creative people at work overtime (Wallace & Gruber, 1989).

The paper is a reflective piece, with the results written autoethnographically by an artist-teacher-researcher-student. Autoethnographic research can be shared as stories, poems, or performances (Bochner & Ellis, 2016; Pace, 2012). This paper includes autoethnographic vignettes written in a first-person voice. The data were collected through the lived experience of the multifaceted identity. In writing about these experiences, the researcher can explore and gain an understanding of the phenomena of identity as a post-graduate research student.

The vignettes are analysed with the published literature and data collected from 17 artist-teachers in Adult Community Learning, to see how their experiences compared to my own. This allows for commonalities and divergences to be identified, and to see if the autoethnographic vignettes are generalisable.

Keywords

artist-teacher-researcher-student, identity, identity model,

higher education, PGR, autoethnography

Introduction

Written from my position as an artist-teacher who is also a researcher and student in post-graduate education, this paper provides an account of how post-graduate research (PGR) students hold multifaceted identities. The paper uses reflective accounts to comment on learner experiences within higher education (HE). The use of autoethnography is intended to give the learner a voice in research into HE.

The paper shows how identities inform each other and change over time. Within the work, I reflect on the fleeting nature of the PGR student identity through a series of autoethnographic vignettes. The vignettes help us understand how identities ebb and flow and inform each other over time. Additionally, they start to demonstrate how identities are often formed in specific locations. The data from the vignettes are then compared to the experiences of 17 artist-teachers in Adult Community Learning (ACL) to see if they are generalisable to others with similar identities to me.

Within my role as an artist-teacher, I work within ACL: an education sector that delivers community-based learning in “local authorities and general further education colleges” (Department for Education, 2019, para 1), typically to adults ages 19+. This positionality becomes important when considering multifaceted identities and the capacity one has for them in terms of time, as artist-teachers in ACL tend to experience precarious working hours (Westminster Hall, 2021). Artist-teachers in ACL are “professional artists and teachers who are dedicated to both and have the competencies needed to work in and through art and adult community learning” (Cairns, 2022a:528). This definition was co-created with other artist-teachers (n=10) working in the sector over two focus group sessions. The artist-teachers were from eight local authority ran ACL centres, across five English regions (East of England, Greater London, South East, South West, and Yorkshire and the Humber).

This paper is written autoethnographically, as I use writing as a method of inquiry and meaning-making (Adams et al., 2014; Bochner & Ellis, 2016). Within this inquiry, I am discovering what it means to inhabit the identities of artist, teacher, researcher, and student. Through the thick description of the four identities that I am embedded in and writing about, I can provide an understanding of them to others (Ellis et al, 2011) by sharing my emotions, intentions, and meanings experienced (Ellis, 1993). The intention is to create writings that will resonate with those similar to myself.

This paper will first outline the materials and methods used in more depth. The four identities; artist, teacher, researcher, and student, will then be delineated in a series of vignettes, presented roughly in chronological order. Though it must be stated that some time frames overlap and criss-cross, this is not always explicit within the writing. To avoid detracting from the stories, the analysis will take place within the discussion section of this paper (Bochner & Ellis, 2016). The four identities will then be discussed with published literature on multifaceted identities from an art and education perspective (Daichendt, 2010; Reardon, 2008; Thornton, 2013; Vella, 2016). Additionally, the vignettes will be analysed with artist-teacher in ACL participant data (n=17). The discussion will then introduce visual models of exploring multifaceted identities; the tetrad identity model and the network of enterprises.

Materials and methods

This paper uses mixed QUAL-qual methods. The research employs autoethnography as the core qualitative component and draws on interview data as a supplementary qualitative component (Morse, 2009).

Autoethnography

The vignettes draw on evocative autoethnography by using a first-person voice (Bochner & Ellis, 2016). They have been kept “short and lively” to show snapshots of my lived life (2016, p. 26), rather than being a narrative story that follows linear time with a beginning, middle, and end (2016). They are episodic (2016,) and aim to “immerse readers in an experience as a means of understanding it” (Adams et al, 2014, p. 86).

The use of autoethnographic writing is intended to make transparent my positionality and lived experience and to “advance theory” around multifaceted identities (Adams et al., 2014, p. 38; Bochner & Ellis, 2016, p. 185). To do this, the vignettes draw upon memory work (Bochner, 2012; Bochner & Ellis, 2016), in which I recall past events, in a process of introspection “as it happened then and as I re-experience it now” (Adams et al., 2014, p. 66), to make sense of the situation. The stories are not “deliberately fabricated” (Ellis, 1993, p. 726) as they can only be recalled as I remembered them. As an autoethnographer, I cannot “reconstruct the past exactly” (Bochner & Ellis, 2016, p. 241). This is unproblematic as autoethnography is unconcerned with truth. Instead, I try “to create a sense of verisimilitude” the appearance of truth, which comes from describing and understanding experiences (Adams et al, 2014, p. 85). Instead, the “theoretical plausibility of a given story” (2014, pp. 82-3) is more important. To test this, readers should be able to answer ‘yes’ to the following: “could the story have happened in the way that narrator and characters describe?” (2014, p. 95) and have a “likeness to life” (Ellis, 2004, pp. 194-5; Bochner & Ellis, 2016, pp. 241-3).

In line with Ellis, my use of episodic short stories does not include "literature reviews, methods section, or theoretical frames” (Bochner & Ellis, 2016, p. 195). Instead, the purpose of the vignettes is to get the reader to think 'with', rather than 'about' the story (2016), to help the reader consider how the story relates to their life. Autoethnography is concerned with the generalisability of a story, the aim of my vignettes is for them to resonate with the reader and make sense in their lives (Adams et al., 2014; Bochner & Ellis, 2016; Ellis, 2004), and identities, multifaceted or singular. The stories must be reliable, as the perceived success is based upon whether the story “speaks to” readers about their own lives (Pace, 2012, p. 3). It is anticipated that the findings from this research will be generalisable to other PGR students and should prompt them to consider which story they resonate most with (Bochner & Ellis, 2016).

Interviews

Additional materials used in the discussion of the vignettes come from artist-teacher participants (n=17). These data show the phenomenon of other artist-teachers also holding multiple identities.

The sampling concentrated on selecting specific groups “that it might be reasonably expected to provide relevant information” (Denscombe, 2021, p. 109). Within this research, this was deemed to be artist-teachers, managers, and learners from an ACL context. However, this paper focuses on artist-teacher data. Morse et al. (2021) state that the data should meet the analytical needs of the research (2021), and it was the artist-teachers’ insider knowledge that was sought.

Interviews took place between August and December 2021, and two additional interviews took place between January and March 2022. All interviews took place online due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and the geographical location of the participants.

Seventeen artist-teachers working in ACL have been interviewed. Twelve participants were sampled through multi-stage sampling, selected from a previous online survey sample (Denscombe, 2021), and a further five were recruited from snowball sampling, where participants suggest other potential participants (2021). The demographic data of artist-teachers surveyed are as followed; 89% (n=8) identified as female and 11% (n=1) as male. No participants identified in any other way. The age range of participants was 30-70. Artist-teachers have been identified to be from 14 different settings (ACL centres). Additionally, one participant was identified as self-employed. Interviews were held with participants in providers across seven of the nine English regions, plus Wales; this participant was sampled through snowball sampling. Most of the responses came from the East of England (n=6), followed by the South West (n=3).

Ethics

This research has been approved through Norwich University of the Arts and University of the Arts London University Research Ethics procedures. Participant consent was obtained before interviews were conducted. Participants and their settings are anonymised to ensure that they are not identifiable in the results. This allows the potential for participants to be more open and possibly critical in their responses, whilst being protected. Similarly, my own ACL setting is also anonymised.

Within this research, I drew upon ethical considerations of autoethnography. I engaged in friendship-as-method, positioning the participants as humans with feelings rather than as objects to gather data from (Ellis et al, 2014). Participant well-being was paramount (Charmaz, 2003). However, once the interviews had been conducted analysis of the data took precedence (Charmaz, 2003).

Results

Early art memories

My earliest memory, aged three, at the university day-care centre, a nursery that my Nan worked in - the only reason I was here, rather than at the village nursery held in the village hall, a place I had refused to return to after having a plastic red teacup with large yellow flowers thrown at me.

An early start and drive by car, arriving with the workers early, rather than with the other children half an hour later. An opportunity that meant I got to unlock the door, press the combination of numbers, and turn the lock.

A large building with long corridors, bright lights, and a distinct smell of artificially scented orange disinfectant. Sitting at an easel painting a picture with Mary – it later transpired she was called Laura, positioned as close to the nursery room door as possible for a quick getaway - I did not enjoy education at this young age.

Three boys, Matthew, Jacob, and Niesen, on a large blue bean bag, sat across from us, as we squeezed onto one chair and wondered who would get to take home our collaborative masterpiece at the end of the day.

Four pots of thick ready mixed paint that smelt of chalk and chemicals, large clunkily wooden paint brushes – one for each plastic pot with a safety lid, no water. Pastel-coloured A3 sheets of sugar paper waiting for a brush stroke. Names are neatly written in the left corner with a black marker pen. The work was taken and hung from the ceiling to dry.

Avoiding worksheets and outdoor play, this is where I stayed until my Nan appeared at the door at lunchtime. Over to the onsite Chinese restaurant for overcooked rice and packets of tomato ketchup in a beige polystyrene take-away carton with a white plastic fork, regaling my tales of painting – was I an artist then?

First exhibition

The question becomes ‘when did I become a professional artist?’, rather than ‘when did I become an artist?' As I think that I have always been one.

The first time I recall feeling like a professional artist was on the occasion that I saw my artwork hanging in the gallery. It was April, going into May 2013, during my Art and Design Foundation. In the art studio, I see a poster pinned to the otherwise empty notice board. An open call for student art. Open for just two weeks. But open nonetheless to the public. My first real* exhibition.

*Here I am discounting educational organized exhibitions

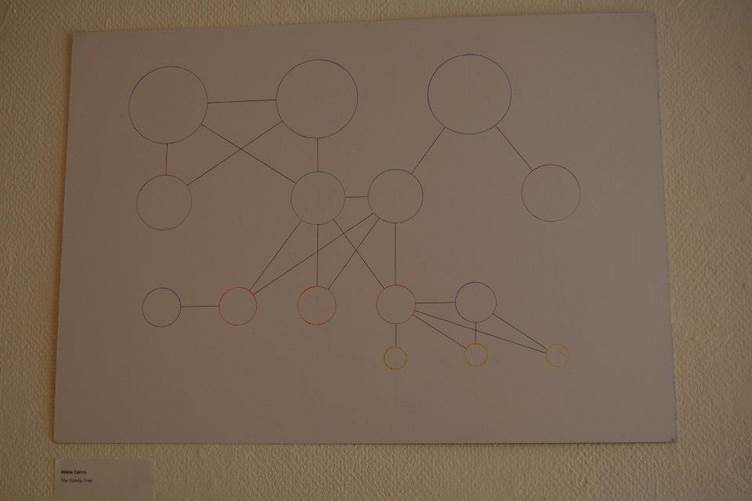

Artwork accepted. An A3 mount board - thick cardboard black on one side, white on the other - adorned with an array of differently size circles and lines, the description reads ‘the family tree’, each circle colour coded. Organized and minimalist. Some content was redacted for ease and symmetry.

Created on my bedroom floor – pointedly outside of education – with a pencil, compass, ruler, and five coloured fine liners; blue, green, red, purple, and yellow. The pens were not touched until the pencil lines were exacting.

Private view unattended, or perhaps un-hosted, I arrive at the gallery with my Mum and grandparents a week into the exhibition. My grandad takes a picture of the outside of the gallery and then of my work. I feel proud.

A moment of feeling that I've made it, or at least that I have made artwork that now hangs in a gallery. I have made it of my own accord and in my own time and with my own resources. I feel as though I own the work that hangs on the white gallery wall, unframed, another of my decisions. One that I have stuck to ever since.

In hindsight, this may not have been the feat that this young artist saw it to be, the exhibition accepted all work put forward. The exhibition is undocumented on their website.

Figure 1. Authors own work, 2013, Family Tree, Pen on Mountboard

From art student to student teacher

The time sequence of events is unclear in my memory. It is 2016, and I have just graduated from Norwich University of the Arts with a BA in Fine Art. It is mid-June, and I find myself at a post-graduate open day at a local university. The initial plan upon graduating was to undertake an MA in ‘Art, Design and the Book’ at the same institution. However, due to cuts, the course, hosted at an art gallery, is no longer running. I needed a plan B and found myself back in the place where three years prior I spent a year completing my Art and Design Foundation, albeit in the adjacent one-storied further education (FE) art block. Now my destination is the second of three floors in the specially built higher education (HE) building, an outer wall adorned with a large logo. A building I had not been able to enter before, with the swipe card-only access and photocopiers on every landing.

However, recently heavily advertised on the radio, here I am.

Up the two flights of stairs, each split into two with a small balcony overlooking the car park. Stack of stock, piled high underneath, covered in blue tarpaulin, ready and waiting on crates.

Second floor, along the brightly lit corridor, sparse of other people. An office, door ajar. Walking onward towards an open door to a classroom. Door open. A tutor waiting. Mature, female, friendly, and piles of application forms. Explaining I've just graduated with my degree and want to get into teaching. I want to teach foundation. I don’t want to teach teenagers.

I laugh at something; my sunglasses fall off my head onto the floor. I pick them up.

“To apply fill out this form and return it” words now fading, but something to that effect. It all seemed so easy, fill out this form, and you’ll be a teacher before you know it.

Sometime later hours or days, the form is completed and returned, along with student finance – without a hitch. Superstitiously I think is a good sign. Usually, with things like this, I think, something always goes wrong. Recalling the student finance dance each year of my BA as less than smooth sailing.

Accepted. The news comes by letter. Start date printed in bold black ink.

Am I a teacher now? A student? Am I still an artist?

The new girl

Day one of teaching adults came months after being offered the job, covering for a veteran tutor, who had by all accounts been teaching this class at ACL since before I was born. No pressure.

I arrived early, though not as early as some students. I looked at them. They looked at me. The penny dropping, I was not their usual tutor. Blindsided by my arrival. As had I, having been reassured they would be pre-warned.

Each greeted me with a handshake and a few confirmations that I definitely was not their usual tutor. While it was a new class, I was definitely the only new girl. Everyone else had been here before.

They welcomed me into their community. We draw with our eyes closed and then with our non-dominant hands. By the end of the session, I am definitely their tutor.

I am no longer a student

I am going to finish my MA in Fine Art imminently. I sit in the university café, which is attached to the gallery space I and four others are exhibiting in for our end-of-year show.

Two white walls, a large window, and the fourth wall is a void, where the café and gallery meet. The floor is dark grey rubber and adorned with the words, with my words, ‘we are here’.

Large, white, shiny vinyl. Justified to the right-hand side of the gallery opening. The words are stacked like stairs.

we

are

here

I sit back on the worn brown leather sofa, warn in a way only a café sofa can be, overused and faded. Springs gone. We are here, but we will not be for much longer. ‘Then what?’ I ponder.

I eat my cake. I will miss the gluten-free coffee cake. The cups of tea, lunches with friends, and the view of the waterfront.

It dawns on me that, more so I will miss being a student. In a few weeks, I will graduate and no longer be a student, for the first time since I was four, abandoned at nursery. I conceded that I have done well to avoid not being a student for this long.

Another gown. Another hat. Another ceremony. How I wish I had kept the hats. The three mounted next to each other, I think, would make a great piece of wall art. Oh well. Just like that, it is over. I am no longer a student.

The MA show is removed. The vinyl lettering brings with it years of dirt. The words

we

are

here

remain on the floor, where the dirt has been pulled up. A ghost of a message. A piece of evidence that it had happened.

The letters themselves come up in strips. Tearing and sticking to each other. Holding on. They do not come easily. One large sticky ball of white vinyl, and some dirt. Now not so shiny goes into the bin.

im

not

here

The MA changed me, and I changed the fabric of the place.

Figure 2. Authors own image, 2018, we are here (removed)

Upper case R, lower case r

I am a researcher. I guess that I am one at least. I research things. I sit at my laptop or with a book open. Sometimes both at the same time and research.

I’ve been researching for years throughout every stage of education and in the art studio.

In 2020 at the start of the PhD., I became a Researcher with a capital R. However, back then I was just a researcher. Lowercase r.

Tuesday Mornings

Turn the laptop on. Turn on the plug. Plug in the power cables. Navigate the online learning environment. Untangle the microphone. Locate the light. Find the USB ports. Log into the online portal. Connect to video and audio. Allow permissions.

“You are currently the only person in this conference.”

Wait for learners. Log in to emails. Verify password. Wait for the Microsoft verification call. Answer phone. Press the hash key.

“Your login verification has been successful.”

Check emails.

9.20am. Learners entre the virtual classroom. One-by-one. “How are you?” on repeat. “We’ve still got ten minutes if you want to grab a cup of tea.”

Don’t make me leave

Being a student is one of my favourite things to be. Not for the student discount, or student nights, but for the learning and structure. Each time I complete a course I find myself applying for another. This desire to be within education is part of the reason I ended up teaching. I figured that if I was teaching, I'd never have to leave.

Turns out teaching in education and being a student are two very different things.

To be a student gives me purpose and drive, not to mention deadlines. It is an identity that I am very comfortable being in.

This is who I am

“When are you available to teach next year?”

The question that comes around every spring. Every year, for the past five years I have kept Tuesdays free for ACL.

Working hours are not guaranteed. But Tuesdays are always kept free.

Why. Because I am an artist-teacher in ACL and to be an artist-teacher in ACL. I need to be teaching art in ACL. Without that the identity fails.

It is who I am. It is what I do.

Researcher: The first conference

Five outfits go into a small hard-shelled black carry-on suitcase. They come out again. They go back in again.

I am preparing for my first conference. Outfit choice probably should not be the biggest stress. However, the papers are written – they have been for a while, and the presentations are also prepared. Printed. Saved on a USB stick. Backed up on the cloud and emailed it to myself too. Just in case.

All that remains is to pick the outfits and check the trains, again, and perhaps work out which fork you are supposed to use first.

Discussion

In this discussion, the presented vignettes will be discussed and analysed with the published literature and artist-teacher in ACL participant data. These data show that the phenomenon of holding multifaceted identities is not unique to me. The discussion will then introduce visual models of identity, which help us to understand multifaceted identities and where each of these identities starts and ends. The PGR student identity is shown to be fleeting but impactful on future identities.

My artist, teacher, researcher, and student identities have been formed at different stages of my life. My artist identity started to form at age three but was solidified in further and higher education and professional practice. My teacher identity was formed in the classroom, with learners, where I enacted the role of the teacher until I became one. My student identity has ebbed and flowed. I have been a student for most of my life, but not continually, and as I write this, I am aware that shortly I will cease to be a student once more. My researcher identity is one I had not considered until becoming a PGR student. The very title of the role dictates this. I used the experience of writing these vignettes as a way of inquiring into my own identity and making sense of it. In this way, they are very much reflective pieces. In analysing these with the published literature it became clear that the phenomenon of holding multiple identities was not unique to me.

Alan Thornton (2013), a writer on artist-teacher identity, provides commentary on this dual identity but also comments on additional identities one might hold, including that of the researcher and student – echoing my lived experience and the findings shared within my autoethnographic writing. Thornton provides an overlapping concepts figure (2013) which shows how the artist-teacher is formed (Figure 3). The emphasis of this figure is the equal weighting it has on each role, a key point for Thornton.

Figure 3. A reproduction of Thornton’s overlapping concepts figure (2013)

However, his figure does not accurately describe the artist-teacher as equalling being made up of ‘artist’ and ‘teacher’, as the middle sector is not equally made up of the outer two and currently leaves much of the artist-teacher unrelated to both. Additionally, and possibly, more importantly, the figure neglects the researcher and student identities also outlined by Thornton. Thornton (2013) refers to the artist-teacher-student. He defines this as an identity that evolves as the individual “[r]eflect upon their practice to improve it... [artist-teachers] simultaneously engage in teaching and learning” (2013, p. 7). This is something he also comments on in earlier work, outlining the teacher-student as an individual, “no longer merely the-one-who-teaches, but one who…[is] taught in dialogue with the students” (2011, p. 32). Thornton suggests that the student identity can exist outside of formal educational contexts.

The student

However, my autoethnographic writing does not reflect this. Within my vignettes, the student identity is linked to being within an educational context. The student identity ebbs and flows; within my vignettes my student identity started in early childhood and continued into adulthood and higher education. My research with other artist-teachers in ACL found that at some point in their professional histories ten of 17 participants were simultaneously artists, teachers, and students in HE. Thirteen participants at some point had been HE students for art-based courses, while eight had been education students within HE at some point in their life histories. This shows the identity of the artist-teacher as strongly linked to the identity of the student.

The student identity is important, as it is an identity many embody before gaining the identities of artist and teacher. Thornton (2013) states that the student identity is important for the artist-teacher, as it is within art education – at the post-compulsory level – that art students realise that they can become art teachers (2013). Showing how vital the student identity is in the formation of the artist-teacher identity. My research revealed that all participants (n=17) had been students at some point in their education. From the perspective of my research, this is particularly noteworthy from an ACL context, as there are no legal requirements for qualifications within this sector, teaching or otherwise (Augar Review, 2019), unlike those going into teaching within compulsory education.

The researcher

Thornton (2013) goes on to suggest that the researcher's identity is “ever-present” from childhood (2013, p. 118). This was not something that I experienced. Within my vignette Upper case R, lower case r, I reflect on not feeling like a researcher until this role was in my PGR title, despite the research that I complete daily within art practice and teaching practice. Additionally, just one of my participants listed the researcher as one of their identities (Table 1).

...when I when I did my BA, I wasn't mature enough to actually be a proper researcher. Umm but I was definitely kind of a student and I was definitely creative. (Artist-Teacher A, Female, 50-54, North East)

For this participant, their researcher identity only came after the completion of her undergraduate education and had progressed into post-graduate education. However, as an undergraduate, she could identify as a student and creative, perhaps, showing this to be a more difficult role to embody or acknowledge than others, such as student. This contrasts my experience and that of Artist-Teacher A.

Thornton goes on to suggest that all teachers should be researchers, to some degree, regardless of whether they are a “generalist or specialist teacher” (2013, p. 117). However, this was not found to be true for my artist-teacher participants.

The artist-teacher

James Daichendt (2010), whose work addresses the philosophy of the artist-teacher, also comments on how individuals become artist-teachers. He suggests that individuals may decide to become an artist-teacher, due to their artist-teachers (2010). He states that this can happen in both positive and negative cases of educational experience, with the individual wanting to return to change the system or to emulate their artist-teacher, to gain similar status. Vella’s (2016) interviewees showed both in action, her interviewee Beverly Naidus had ‘dynamic teachers’ who were “great risk-takers and role models” (2016, p. 10), while Shady El Noshokaty found the education they received to be oppressive (2016). Walter Gropius’ (Daichendt, 2010) own art education was just as lacking. He was inspired to avoid the same pitfalls, which lead to his design of the Bauhaus building, which was “divided into three different wings…the workshops, studio spaces and the north wing all have particular spaces” (2010, p. 104). In contrast, Vanalyne Green (Reardon, 2008), an artist-teacher in HE reported that her relationship with her art tutors was so strong, that she compares the experience to a “duckling being imprinted” and credits them for the artist-teacher she is today (2008, p. 197). Daichendt uses Anni Albers as an example of this, as someone who followed in their teacher's footsteps and started to teach and share her passion, in the same way as they had (2010). Bickers (2010) adds that individuals can be further motivated to do this by others, with art schools inviting successful graduates to teach part-time (2010). This is unlikely to happen in ACL, as learners leave courses with a Level 2 qualification, or below (Local Government Association, 2020).

The artist-teacher-researcher-student

My autoethnographic writing and the four identities explored within Thornton's work; artists, teachers, researchers, and students, informed the development of the Tetrad Identity Overlapping Model (Figure 4) (Cairns, 2021).

Figure 4. Tetrad Identity Overlapping Model (Cairns, 2021)

The model highlights how the four identities come together, starting with individual identities and moving inwards towards a tetrad identity. While the model was developed based on the artist, teacher, researcher, and student identities, they can easily be changed to fit others’ identities – this is important as the intention is for a model with real-life applicability (Table 1).

Table 1. Participants with a multifaceted identity

|

Participant |

Identity #1 |

Identity #2 |

Identity #3 |

Identity #4 |

|

A |

Artist |

Teacher |

Researcher |

|

|

B |

Artist |

Teacher |

Designer |

Student |

|

C |

Artist |

Teacher |

Caterer |

Student |

|

E |

Artist |

Teacher |

Student |

|

|

F |

Artist |

Teacher |

Writer |

Student |

|

G |

Artist |

Teacher |

Physiotherapist |

Student |

|

H |

Artist |

Teacher |

Student |

|

|

I |

Artist |

Teacher |

Curriculum leader |

Student |

|

L |

Artist |

Teacher |

Other |

Student |

|

K |

Artist |

Teacher |

Student |

|

|

O |

Artist |

Teacher |

Student |

|

|

P |

Artist |

Teacher |

Church leader |

Student |

|

V |

Artist |

Teacher |

Student |

|

|

W |

Artist |

Teacher |

Curator |

Student |

|

X |

Artist |

Teacher |

Student |

|

|

Y |

Artist |

Teacher |

Student |

|

|

Z |

Artist |

Teacher |

Church leader |

Student |

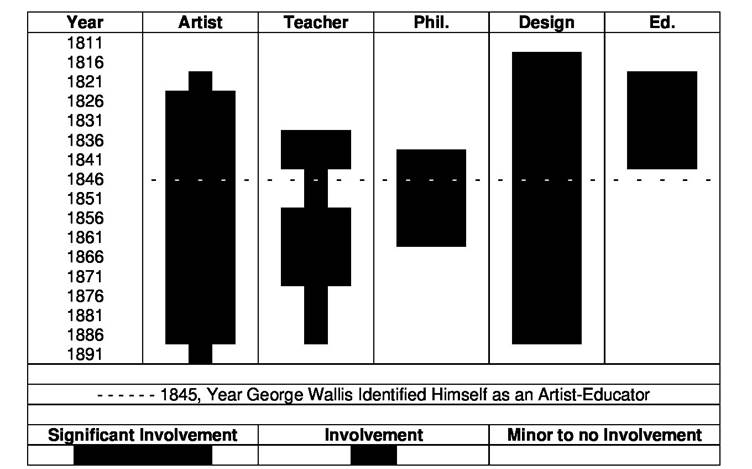

This work resonated with another aspect of Daichendt’s work, networks of enterprises. Daichendt used Wallace and Gruber’s (1989) networks of enterprises to record the career of the earliest recorded artist-educator, George Wallis. Networks of enterprises were first used with creative people at work (Wallace & Gruber, 1989). Wallace and Gruber outline network of enterprises as encompassing several related activities that allow the “creative person” to continue towards goals in different areas (1989, p. 11).

Networks of enterprises are “a kind of visual CV and a tool for personal discovery” (Cairns, 2022b, para 4), which chart multiple enterprises over time, usually years. Each year the significance of each is charted from none to significant. Daichendt uses the network of enterprises to highlight how an individual is often engaged in several related activities throughout a lifetime and uses the network of enterprises to visualise this. He uses the network of enterprises to chart the life of Wallis, including the date Wallis first used the term artist-educator (2011) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. A reproduction of Daichendt’s network of enterprises for George Wallis (2011)

Within the networks or enterprises, the width of the columns indicates the level of involvement in each enterprise, from none to significant. This highlights the “trade-off” between different enterprises (Wallace and Gruber, 1989, p. 12). Daichendt (2011) outlines that networks of enterprises are tools to document the diverse aspects of one’s life, in the case of Wallis this tool “track[ed] the streams of thinking” that led him to identify as an artist-educator (2011, p. 71), one of which was his identity within education. Which incidentally was a negative experience (Daichendt, 2010), relating to Thornton’s notion of art school experiences informing future identity direction.

Wallis’ network of enterprises (Daichendt, 2011) (Figure 3) supports the need for the tetrad identity model, as in 1845, the year Wallis identified as an artist-educator, he was also a philosopher and designer, giving him the tetrad identity of artist-teacher-philosopher-designer. While the network of enterprises was originally intended for creative people, it can be used by anyone with a multifaced identity. This might be particularly pertinent for other post-graduate research students and their lecturers.

Figure 6. Abbie Cairns’ network of enterprises

My network of enterprises shows that I am also involved with diverse enterprises (Figure 6). Both show how identity can be made up of numerous components that change over time.

My autoethnographic writing suggests, that for me, my identities are linked to specific contexts or locations in Early Art Memories I am an artist at an easel, in The First Exhibition, I am an artist in a gallery, in From Art Student to Student Teacher, my identity changes as I move from an art university to a teacher training course, in I am No Longer a Student, I am graduating, in Tuesday Morning I am an artist-teacher in ACL, in an online classroom, in Researcher: The First Conference I am a researcher at an in-person conference for the first time.

The published literature also comments on this and the role that locations and communities of practice have on how we define ourselves. Adams (2007) suggests that this happens as identity can be defined socially (2007). As individuals enter dialogues with others in their new community of practice (CoP) a transformation takes place (Lave and Wenger, 1991; Thornton, 2013). This is illustrated by the works of a participant from my grounded theory research:

I was just surrounded by teachers instead of artist. So, I was working there three days a week and I suppose in that sense you know I was more in a teaching environment than an artist environment […] I wasn't surrounded by other artists. Which is, I think, a big part of artistic identity, being surrounded by peers that are doing what you're doing, you know [...] Whereas there [...] they didn't have the same art education, or interest that I had. So, conversations weren't about art or creative practice (Artist-Teacher F, Female, 35-39, East of England)

The extract highlights how she became a teacher before an artist-teacher in ACL, teaching outside of art in a school context. She found herself embedded in a teaching environment with other teachers led to the identification of teacher. An identity that Artist-Teacher F was not completely happy with. She found the experience of being surrounded by teachers negative. She was being enclosed and cut off from her artist self and unable to engage in legitimate peripheral participation (Wenger, 2000). The extract comments on the role time spent in certain locations and CoPs plays in identity. Artist-Teacher F felt like a teacher as she was spending most of her week in a teaching environment, suggesting that the amount of time spent in a professional location may impact identity.

Conclusion

Throughout this autoethnographic research, I have found that I group my identities, I am an artist-teacher, and I am – at least currently – a researcher-student. Before undertaking this work, it had not been clear to me that I had separated my post-graduate research student identity from my artist-teacher identity. Through reflecting on this within this paper, I have gained an awareness of the former being a fleeting identity. I am an artist-teacher-researcher-student but will not identify in this way forever. Instead, these identities will be part of my history and will contribute to my future identity, as was the case with Wallis (Daichendt, 2011). The network of enterprises helps us to document the ebbs and flows of identities as life changes.

My vignettes and the published literature showed the role that location and communities of practice play in identity (Adams, 2007; Lave and Wenger, 1991) and suggest that if you want to identify in a certain way, you must spend time in the spaces synonymous with that identity. The impact of the recommendation to embed yourself within locations associated with that identity may be beneficial to identity formation.

This work is not only important for PGR students, but also for those who teach them and those that teach within any other post-compulsory education (Thornton, 2013). This article goes some way to amplifying the voice of post-graduate students in research concerning the sector. It becomes clear that those who teach act as models for future identities. Perhaps the teacher needs to decide if they want to be emulated or condemned by their students in the future (Daichendt, 2010).

The use of the Tetrad Identity Overlapping Model (Cairns, 2021) and the network of enterprises (Daichendt, 2011; Wallace & Gruber 1989), helps us to acknowledge that each individual will have their own mix of identities, which are both unique, and common and which ebb and flow throughout life.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge my supervision team at Norwich University of the Arts for their support and guidance and my participants, who have given so much of themselves to this project, without which this research would not be possible.

Declaration of interest statement

As an active artist-teacher working in ACL I have a vested interest in the research into this role.

References

Adams, J. (2007). Artists becoming teachers: Expressions of identity transformation in a virtual forum. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 26(3), 264–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-8070.2007.00537.x

Adams, T. E., Jones, S. H., & Ellis, C. (2014) Autoethnography. Oxford University Press.

Augar Review. (2019). Independent panel report to the Review of Post-18 education and funding May 2019. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/805127/Review_of_post_18_education_and_funding.pdf

Bickers, P. (2010). Those who can, teach. Art Monthly, (336), 14. http://www.artmonthly.co.uk/magazine/site/issue/may-2010

Bochner, A. (2012). Bird on the wire: Freeing the father within me. Qualitative Inquiry, 18(2), 168-173. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800411429094

Bochner, P. A., & Ellis, C. (2016). Evocative autoethnography: Writing lives and telling stories. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315545417

Cairns, A. (2021). Artist-teacher identity (trans)formation: Understanding the identity of the artist-teacher with the use of an artist-teacher identity model. InSPIRE FE. 1(2). https://nua.repository.guildhe.ac.uk/id/eprint/17373/1/ACairns_Artist-Teacher%20Identity%20%28Trans%29formation.pdf

Cairns, A. (2022a). An interrogation into the need for a new definition for the artist-teacher in adult community learning. The International Journal of Art and Design Education, 41(4). https://doi.org/10.1111/jade.12436

Cairns, A. (2022b, November 1). Networks of enterprises. https://nexus-education.com/blog/networks-of-enterprises/

Daichendt, G. J. (2010). Artist-teacher: A philosophy for creating and teaching. Intellect. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv36xw1vs

Daichendt, G. J. (2011). The nineteenth-century artist-teacher: A case study of George Wallis and the creation of a new identity. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 30(1), 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-8070.2011.01673.x

Denscombe, M. (2021). The good research guide: For small-scale research projects (7th ed.). Open University Press.

Department for Education. (2019). Statistical data set: Community learning. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/fe-data-library-community-learning

Ellis, C. (1993). Surviving the loss of my brother. The Sociological Quarterly, 3(4). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.1993.tb00114.x

Ellis, C. (2004). The ethnographic I: A Methodological novel about autoethnography. AltaMira Press.

Ellis, C., Adams, T. E., & Bochner, A. P. (2011). Autoethnography: An overview. Historical Social Research (36)4, 138.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511815355

Local Government Association. (2020). Learning for life: The role of adult community education in developing thriving local communities. https://www.local.gov.uk/learning-life-role-adult-community-education-developing-thriving-local-communities-handbook#download-the-report-as-a-pdf

Morse, J. M. (2009). Mixed methods design: Principles and procedures. Routledge.

Morse, J. M., Bowers, B. J., Charmaz, K., Clarke, A. E., Corbin, J. M., Porr, C. J., & Stern, P. N. (2021). Developing grounded theory: The second generation revisited (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315169170

Pace, S. (2012). Writing the self into research: Using grounded theory analytic strategies in autoethnography. TEXT, 16(Special 13), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.52086/001c.31147

Reardon, J. (2008). Ch-ch-ch-changes: Artists talk about teaching. Ridinghouse.

Thornton, A. (2011). Being an artist teacher: A liberating identity? International Journal of Art & Design Education, 30(1), 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-8070.2011.01684.x

Thornton, A. (2013). Artist, researcher, teacher: A study of professional identity in art and education. University of Chicago Press.

Vella, R. (Ed.) (2016). Artist-teachers in context: International dialogues. Sense. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6300-633-0

Wallace, D. B., & Gruber, H. E. (1989). Creative people at work: Twelve cognitive case studies. Oxford University Press.

Westminster Hall. (2021). Westminster Hall debate: Third report of the Education Committee, a plan for an adult skills and lifelong learning revolution, HC 278. 15 April 2021. https://parliamentlive.tv/event/index/f3d210ee-0aab-4050-9fe5-e8b09e5f4ed2