The secret art of pedagogical alchemy: Creating joy, resistance and hope in neoliberal times

Craig Wood1

1Queensland Teachers' Union, Brisbane, Australia

Abstract

This paper reveals secrets. Like their Renaissance counterparts, pedagogical alchemists often work in secret networks as they struggle against dominant forces. Pedagogical alchemists seek to transform assemblages of neoliberal education policies, shifting enactments of such policies from replication of systemic hierarchies and oppressions towards teacher and student experiences of joy, hope, and resistance. The secret art of pedagogical alchemy adopts critical praxis research method that amplifies epistemological insights arising from teacher experience. This paper utilizes performative autoethnography and social fiction to interrogate the influence of socio-political context on the labour of an 8th grade school-teacher. The secret art of pedagogical alchemy locates the experiences of a pedagogical alchemist whose 8th grade history class includes a unit of work on Renaissance alchemist Isabella Cortese. The experiences are framed by globalised, neo-liberal education policy assemblage. Like the writings of Renaissance alchemist, Isabella Cortese, the voice of the 8th grade history pedagogical alchemist is performed in quatrains that are written in iambic pentameter.

Keywords

pedagogical alchemy, teacher resistance, neoliberal,

critical praxis research, reflective practice

Introduction

This paper reveals secrets. Just like the clandestine practices of alchemists throughout different times and diverse places, I contend that there is an art that can be termed pedagogical alchemy which is conducted in secret, and it is an act of hope and resistance against dominant forces. I also contend that the practice of pedagogical alchemy can be as creative as it is secretive.

Contemporary pedagogical alchemists work covertly in schools throughout the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), including Australia, Canada, New Zealand, United Kingdom, and the USA; countries where teacher practice is subjected to globalised, neoliberal assemblages of education policies (Lewis et al., 2020; Rizvi et al., 2022). The impact of neoliberal policies on the teaching profession has been reported in the field of education research (Apple, 2017; Wrigley, 2006). Such policy assemblages typically result in narrowing of curriculum that privileges hegemonic knowledge, marginalises diversity, and ignores students' uniqueness. Hegemonic knowledge is positioned by dominant forces as universal truth and it is reified through curriculum and assessed using standardised tests (Apple, 2013a; Sahlberg, 2016; Wrigley, 2006). The same neoliberal assemblages of education policy are engaged in systematic stripping away of teacher professionalism and pedagogical innovation, while privileging low-risk approaches to teaching that result in learning that is decontextualized, impersonal and irrelevant (Biesta, 2015; Evers & Kneyber, 2016; Lewis, 2015). This approach to education devalues the richness of teacher-student interaction, stifles creativity, and erodes the joy of teaching and learning (Crowther & Boyne, 2016; Olson, 2009; Wood, 2018).

The purpose of this paper is to give voice to, and build community with, pedagogical alchemists. The paper raises awareness of creative and joyful approaches to teacher praxis that resist neoliberal education reforms and that alert teachers who are working in this space that they need not work in secret isolation. Terry Wrigley observes,

Many teachers persist with more enlightened methods, despite the bureaucratic overload or the nagging worry that inspectors from the Ofsted education watchdog might catch them out. (Wrigley, 2006, p. 9).

Joe Kincheloe similarly recognises,

The plethora of small changes made by critical teacher researchers around the world in individual classrooms may bring about far more authentic educational reform than the grandiose policies formulated in state or national capitals. (Kincheloe, 1991, p. 14).

The secret art of pedagogical alchemy joins Wrigley's (2006) call to rethink education, to empower collective voices in the teaching profession, to celebrate innovative models of practice, to develop communities of resistance, and to facilitate the courage to speak back to power. Berry (2016), Mitchie (2012), and Wrigley (2006) identify the power of collective teacher voices to disrupt neoliberal education reforms and reclaim the teaching profession. Reinserting creativity and joy into pedagogy is one way that schools can become enriched sites of student hope, where multiple voices are rehearsed and refined, resulting in strengthened local and global democratic institutions (bel hooks, 1994; Freire, 1993; Giroux, 2011; McLaren, 2007).

This paper is arranged in three sections, and it is written in two voices. This first section is written in my teacher-researcher voice that considers teacher resistance to neoliberal education reforms in the field of education. The second section continues to present my teacher-researcher voice and I discuss my research methodology that applies critical praxis research and performative autoethnography. I explain my choices that underpin this paper which include critical teacher reflection and using story and social fiction. The methodology section also discusses social fiction as research and introduces Malcolm as a character who performs a representation of pedagogical alchemy. The third section cross-fades between my teacher-researcher voice and the voice of Malcolm who provides a teacher praxis-based voice and that shows pedagogical alchemy as an act of teacher resistance in the field of education. Malcolm is a public school-teacher whose praxis is represented in a case study of pedagogical alchemy in teaching praxis with 12-13 year old students in a class of year 8 History. The class are studying Renaissance, and, like the writings of Renaissance alchemist Isabella Cortese, the voice of Malcolm is performed in quatrains that are written in iambic pentameter. Malcolm's quatrains are arranged to develop an understanding of experiences of joy, resistance and hope in schools.

Method

I have approached this contribution to teacher resistance from my dual position as both school-teacher and teacher-researcher, which offers an epistemology of insiderness (Adams et al., 2015, p. 32) to the constructions of knowledge. My work in both roles is underpinned by a commitment to critical reflective practice that seeks to illuminate power and uncover hegemony (Brookfield, 2017; Tripp, 2012). In this paper, I have employed critical praxis research (CPR) as method that Kress (2011) posits is a scholarly pursuit for practitioners which combines theory and practice to challenge hegemony, and which engages with stories of resistance to empower practitioners' voices. My CPR method draws on reflective narratives from my twenty years of experiences as a school-teacher and it pursues the broader CPR agenda to empower teacher voice in the field of education research.

My CPR can be located in the methodological field of performative autoethnography. Autoethnographic research is at the intersection of the personal and cultural; it looks inwards and outwards, and where the researcher assumes the dual roles of both the researcher and the researched (Ellis, 2009; Poulos, 2021). Performative autoethnographic writing recognises the material body as a site of such constructions of knowledge where traumas, joys, and everything between is re-membered (Denzin, 2018; Iosefo & Iosefo, 2020; Mackinlay, 2019; Pelias, 2019; Spry, 2016; Upshaw, 2017). In this paper, I am researched when I look inwards at representations of teacher praxis that are performed in Malcolm's voice, and I am the researcher as I analyse Malcolm's practice and look outwards to locate it in the field of education research.

My CPR method began with an outward looking critical review of publicly available documents that impact on school-teachers in Australia. Documents included The Mparntwe Education Declaration (Department of Education, Skills, and Employment, 2019); School Planning, Reviewing and Reporting Framework (Queensland Government, 2015); Sustainable Development Goals (UNESCO, 2015); Australian Curriculum History (ACARA, 2022a); Quality Schools, Quality Outcomes (Australian Government, 2016) and Robert Marzano's Art and Science of Teaching (2007). I viewed these documents through a critical lens that positioned them as neoliberal attacks which adversely impact the teaching profession.

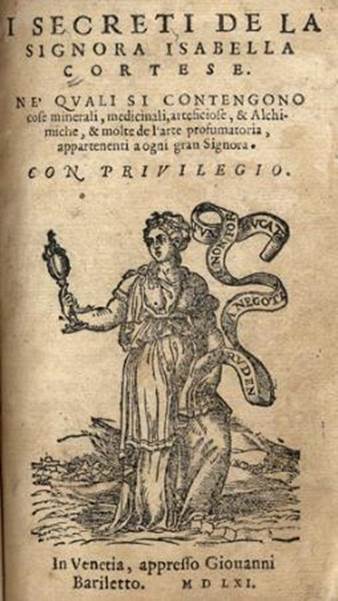

While I was critically reviewing education policy documents as a teacher-researcher, I was also planning a number of units of work in my role as a secondary school-teacher of Arts, English and Humanities. At this time, I found an image of I secreti de la signora Isabella Cortese. I spent several hours looking at this image and searching for related texts and images that could inform a unit on Renaissance Italy. I was captivated by this image, and I was committed to embedding the image in unit of work for year 8 History.

From this point in time, I engaged in a process of reflective writing, described by Bolton (2014) as through-the-mirror writing. This process includes a six-minute write, whereby I engaged in free writing for six minutes without interruption. The intention of this process was to allow ideas to emerge, free of constraints of grammar, spelling, punctuation, even story structure. Bolton (2014) suggests that such a writing process can liberate ideas and stories that might be deeply hidden in layers of subconscious, and in so doing, explore issues and find new connections, thoughts, and ideas. I reshaped and restoried the data that emerged from my through-the-mirror writing, revisiting and reframing my praxis-based stories in the neoliberal education policy context of my work as a school-teacher.

As I continued to develop my through-the-mirror reflective process, themes and patterns emerged in the data. My reflections were revealing moments of joy, resistance, and hope that I applied as themes to classify the data. I then set about creatively representing my critical review of policy documents, critical reflection on my teaching units, and data arising from my through-the-mirror writing process, as the experiences of Malcolm.

Representation

In this paper, I have drawn on social fiction as method to create Malcolm. He is a fictional character that emerged in my through-the-mirror writing process. Malcolm represents my critical reflections on the assemblage of education policy and tensions that I have experienced as I seek to disrupt hegemony and enact critical curriculum. Leavy (2013) posits that fiction and non-fiction are not binary opposites, rather that contemporary qualitative research blurs the boundaries between the two in ways that enliven nuance and enable readers to understand complexity in phenomena. Leavy (2013) further identifies benefits of writing social fiction as research that include shifting both the reader and writer to see and think differently, to build empathy and raise awareness of phenomena. Denzin (2014) posits that ethnographic writing can only ever be a storied representation of the past. The result is that researchers can extend the ethics of applying pseudonyms to research participants, to de-identifying entire research contexts, while maintaining the truth of the story. Denzin's idea can be seen in practice in The social fiction series, of which Patricia Leavy was the founding editor, and disseminate research using literary forms. An example of this work is Carl Leggo's (2012) Sailing in a concrete boat which similarly blends poetry and prose to represent his experiences as a teacher, and Leggo represents his experiences as a school-teacher and teacher-researcher through a fictional character, Christian. Ron Pelias' (2016) If truth be told also employs a range of literary devices, including poetry, to disrupt reader's assumptions about what might be truth in his writing.

Further examples of research that is presented using literary devices include Bochner (2014), Clough (2002), and Ellis (2004). Each of these three works include an epilogue which discloses an understanding that some of the stories in their narratives might, or might not, have occurred, and that some of the characters might, or might not, be real or composites of real people. Nonetheless, the truth in their stories is that something like this happened. This reflexive acknowledgement of the writers does not detract the shared experiences of truth that the work offers the reader. The acknowledgement does not diminish the lifelike, believability, or plausibility of the work. Nor does the acknowledgement diminish the goal of the works, which is to evoke emotion in the reader and lead them to consider resistance to hegemony and injustice in their own world. Carolyn Ellis reflects,

For me, the question (is) not whether narratives convey precisely the way things actually were, but rather what narratives do, what consequences they have, and to what uses can they be put. (Ellis, 2009, p. 110).

Discussion

This section shows Malcolm's performance of pedagogical alchemy as a creative act of teacher resistance that can liberate teachers and students from dominant forces. His quatrains give a voice to teacher experiences by revealing his approach to planning and teaching a year 8 unit of work on the Renaissance that is aligned to the Australian Curriculum's History learning area at year 8 level (ACARA, 2022a). The official curriculum recognises that a unit of work about Renaissance Italy and the concentration of wealth and power in city-states, could include an investigation of "humanism, astrology, alchemy, the influence of ancient Greece and Rome" (bold for emphasis) (ACARA, 2022b).

Malcolm's decision to focus on alchemy as a case study of resistance to concentrations of wealth and power in Renaissance Italy subverts the academic rationalist intent of the curriculum, which is preferred by the neoliberal agenda. Academic rationalist curriculum preserves the "knowledge, skills and values of prior generations," (Babalola, 2015, p. 21), reifies "Western canon curriculum that has typically omitted or distorted the history, culture, and background of non-dominant culture groups" (Fickel et al., 2017, p. 102), and reduces learning in History to reciting names and achievements of the likes of Galileo and di Vinci (ACARA, 2022c; Nordtveit, 2016; Parkes, 2013). In contrast, Malcolm's approach to curriculum aims to be self-actualising and critical (Eisner & Vallance, 1974; Marsh, 2009; Pinar, 2012).

As a pedagogical alchemist, Malcom seeks to use education to enrich and liberate the learner by emphasising personal growth and social awareness. In the first quatrain, below, Malcolm begins to reveal his own joy at finding an historical text that he plans to use as a self-actualising teaching resource. The historical text appears below and is the cover of a book, I secreti de la signora Isabella Cortese, written by Renaissance alchemist Isabella Cortese.

Figure 1: I secreti de la signora Isabella Cortese

Note. Image of I secreti de la signora Isabella Cortese, from https://openlibrary.org/books/OL24444521M/I_secreti_de_la_signora_Isabella_Cortese

In this section, I cross-fade between my teacher-researcher voice and Malcolm's praxis voice that is performed in quatrains. My teacher-researcher's voice disrupts Malcolm's quatrains to locate his experiences in the field of education research, and that interpret and categorise Malcom's experiences as joy, resistance, or hope. Joy is explored in three sections: the physical and cognitive responses to a joyful experience; enactments of curriculum that attempt to inspire joy in students; and joy as experienced as a collegial celebration of practice. Resistance is initially explored in two sections which recognise conflicting views on the purpose of schooling and reveals how this conflict manifests as enacted pedagogy. Resistance III appears as an epilogue to this paper. The category of hope positions pedagogical alchemy as future focussed, developing a critical and activist citizenry, and that aims to deliver the promise of UNESCO's (2017) goals to transform the world.

Joy I

An image, nearly five hundred years' old

An alchemy book about making gold,

First printed, Venice, M-D-L-X-I

'Bout Cortese's secrets of alchemy.

You see, when I did first find this picture

What I felt was joy, as a school-teacher.

Joy of connecting with living hist'ry,

A cognitive joy and one that's sens'ry.

The teacher can see visceral learning,

Inside I'm jumping, my stomach's churning,

I'm planning critical pedagogy,

Creative learning, arts-based 'ology.

Wonder where Cortese' book is today,

Who took this photo? What secrets remain?

Wonder if all of it's the secrets are fraud,

Reflect on the sources, challenge us all.

Imagine time - when this book was written.

Imagine place – the writing is Latin.

Here's I secreti de la signora

Isabella Cortese' secrets for you!

Malcolm's joy is derived from finding a teaching resource, I secreti de la signora Isabella Cortese, that is beyond the prescribed teacher resources. He identifies joy pertaining to his identity as a "school-teacher", his "connecting with living hist'ry", and he describes the process as one that is both a "cognitive" and a "sens'ry" experience. Malcolm's first sighting of the image Cortese' work triggers "joy, as a school-teacher". He explains the physical sensation of, "inside I'm jumping, my stomach's turning" because he instinctively sees possibilities for the type of teaching and learning that he values as a pedagogical alchemist. He explains his cognitive processes that unfold, including his plans for self-actualising, critical and creative learning. He can see opportunities to critically challenge the source as well as engaging students' literacy skills as they decode the Latin and make sense of the text as English language learners. In addition to teacher joy, Malcolm experiences joy as a human being interacting with an historical artefact that is 500 years old, and he begins to wonder and imagine about the image of Cortese' book on his screen.

The moment of joy that Malcolm experiences is a result of his continued pursuit of pedagogical alchemy. Malcolm's determination to disrupt his teaching praxis from the constraints of hegemony that are enshrined in curriculum, resulted in the opportunity to begin to plan self-actualising critical and creative learning opportunities for his year 8 History class. The development of his praxis as a pedagogical alchemist, is further revealed as resistance in the following quatrain.

Resistance I

Here's the piece that will frame my teaching –

Forget assessable data leaching.

Disrupt Their power, like Helen of Troy,

Empowered lovers are lovers of joy.

But here's the rub and the reason I say

We need pedagogical alchemy.

The purpose of schooling's more than They tell,

Their labour training myth must be dispelled.

Why would we train Their unemployment queues?

Their purpose of schooling's all just a rouse.

Yes, reading, writing, arithmetic

BUT to make futures more democratic.

We need to commit to lifelong learning,

Quality living data'll start turning.

That's a threat to hierarchies of power,

Those who occupy ivory towers.

For democratised futures we must fight

Our present students, we must enlight'n.

And that means creating moments of joy,

Secret resistance to raise hoi polloi.

Malcolm's teacher resistance arises from an alternative view on the purpose of schooling to that pursued by those who advocate neoliberal education reforms. Malcolm positions the two purposes of schooling as binary opposites whereby "They" and "Their" represents the neoliberal purpose of schooling as being one of training a future workforce that will generate profits for capital. This is underpinned by a steadfast commitment to individualism and competition that unleashes market forces throughout schools' education, which result in entrenched inequity that rewards socio-economic and political privilege of individuals while marginalising diversity (Baltodano, 2012; Connell, 2013; Hill, 2010). Terry Wrigley observes,

Capitalism has always had a problem with education. Since the Industrial Revolution and the early days of mass schooling for working class children, the ruling class needed the skills of future workers but was terrified that they might become articulate, knowledgeable, and independent-minded. (Wrigley, 2006, p.1)

In contrast, Malcolm pursues a purpose of schooling that seeks "democratised futures" that "disrupt Their power". He rejects the view that the purpose of education ought to be vocational training, or "labour training", as "all just a rouse". Models of democratic education and critical pedagogy have been posited in the field education literature and include the work of bell hooks (1994), Paulo Friere (1993), Henry Giroux (2011), Peter McLaren (2005), and Terry Wrigley (2006). McLaren (2005) posits that critical pedagogy seeks to "understand the mechanisms of oppression imposed by the established order" (p. 6). In the case of learning about Renaissance alchemist Isabella Cortese, learning could include a critical investigation of the social, cultural, economic and political features of Renaissance Italy (ACARA, 2022d), as well as relationships between rulers and ruled (ACARA, 2022e). For pedagogical alchemists, critical pedagogy also means maintaining critical awareness of the impact of neoliberal educational reforms on teacher praxis and student learning. In both cases, critical pedagogy seeks to build knowledgeable, articulate, and independent-minded citizenry, which will "raise hoi-polloi."

Hope I

What's school data explicit agendas

Measuring last year's 'gainst next year's trendings?

Then issuing pedagogical rules

Irrelevant to this year's kids in school.

Do we represent students with pie charts?

Do we think of our students as bar graphs?

How can the act of teaching be reduced

To decontextual numbers obtuse?

What do I want for my students to know?

The power of love. The power of hope.

The power of people's power of speech.

These are some powers my classes beseech.

These aren't the powers the Power'd call for.

Their power's emboldened by data walls.

Statistical celebrations of privilege

Muscling up power – like Popeye's spinach.

To critically challenge the Power'd's game

Must be a secret, lest I'll be disclaimed.

But it's my students that I'm struggling for,

Their hope; their future; their voice; and much more.

Malcolm's concluded Resistance I with a secret agenda "to raise hoi-polloi". Then, Hope I reveals some of a pedagogical alchemist's approach to teaching that has a future focus of developing students' voice and, in so doing, inspiring hope. Malcolm rejects representing his students as decontextualised data on a bar graph or pie chart, preferring instead to focus on showing students their own power of love, hope, and speech. This approach is supported by Olson (2009), that sees teachers and school leaders resisting an approach to teaching that sees them "spiralling into a frenzy of uncritical, mindless test score jitters" (p. 6), suggesting instead that learning ought to "inspire transcendent joy" (p.16).

Theopedia (2016) frames the notion of joy from a Christian standpoint, offering that, "joy is a state of mind and an orientation of the heart", that this can be likened to the Greek word Χαρά (Chara), or "calm delight". This framing of the notion of joy, can be juxtaposed with notions of hope that are framed by bell hooks (2003), Daniels (2010), and Freire (1994). Joy is located in the present, whereas hope looks to utopian futures. Joy is a personal, internal response to our place in a moment in the world around us, whereas hope is an outward pursuit of transformation for community. From this understanding, and returning to Malcolm's quatrains, the role of the pedagogical alchemist must be to transform mercury, those heavy burdens of the neoliberal generated experiences in education, into gold, that manifest as experiences of calm delight. Pedagogical alchemists achieve this by challenging hegemony in the curriculum and by inviting multiple knowledges and perspectives. This leads to students creating personal connections with the curriculum and making learning personally meaningful. Such learning privileges the richness of the teacher-student relationship over neoliberal demands for data (Renner, 2009).

Malcolm asserts that empowered rejections of data are not "the powers the Power'd call for," however there is some alignment with the overarching Australian goals for schooling. Australia's Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration contains education goals for young Australians that were agreed to by the Australian federal government and all state and territory governments. By sequencing moments of joy, pedagogical alchemists can create hopeful futures, and such futures are embedded nationally in The Mparntwe Declaration as well as globally in UNESCO's (2015) Sustainable Development Goal 4. Malcolm returns to UNESCO's goals in Hope III, and his approach to enacting The Mparntwe Declaration is considered below, in Joy II.

Joy II

Teaching ought not be by remote control

But our nat'ional educational goals

Listed in the Mparntwe Declaration

A blueprint for the Australian nation.

Preamble in Mparntwe Declaration

Sets out the purpose of education.

Building democracy, and equity,

Social cohesion, and prosperity.

Australia's national goals for schools

Establish the holistic teaching rules.

The unit aim's verbs are where I focus

My pedagogical hocus-pocus.

Imagine learning inspired by verbs

Like 'Wonder at', 'Marvel', 'Dream' and such words.

Spectacular verbs to enliven joy

And transform learning from soulless alloys.

Revealing power in Renaissance times,

Transferable to our own paradigm,

The students will wonder, or marvel at,

Or argue, discuss, about plutocrats.

In Joy II, Malcolm proposes an interpretation of the Mparntwe Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians that is inspired by the verbs that underpin his lesson planning. In applying cognitive verbs like "wonder at" and "marvel", Malcolm continues to reveal secrets of pedagogical alchemy that create joy. He refers to his process as his "pedagogical hocus-pocus", and it contrasts with taxonomies of education objectives posited by Bloom (1956), and Kendall and Marzano (2006). The latter use verbs like "classify", and "investigate", resulting in students learning privileged, hegemonic knowledge. Such verbs accord with the academic rationalist model of curriculum, described by Freire (1970) as the banking model of education that likens students to vessels that are filled with teacher knowledge, and that Malcolm opines is "soulless". In contrast, Malcolm's "pedagogical hocus-pocus" becomes joyful because students "wonder" and "marvel", taking time to imagine their own internal response to a moment in time and place, and then to find ways to communicate their ideas and to develop their voice by arguing and discussing. This approach strengthens citizen's participation, and thereby strengthens democracy, that is one of the aims of The Mparntwe Declaration.

Resistance II

But, "Teach like this, Malcolm," – Marzano's way,

Or D.I., or Flemming, or John Hattie.

"This is the framework we use in this school"

Leaders make choices, not teachers at all.

So now, "do this Malcolm. Teach it this way.

Get it done, or the whole school you betray.

Remember our teaching staff is a team,

Use all of these resources. It's Pearson's dream."

But I don't subscribe to powers that be

Nor use the resources from overseas.

I do my own planning for my own class

I work in secret, avoiding fracas.

Translate these words, it's a lit'racy task,

What's "I secreti, signora?" I ask.

And we're away. We are having success.

Pedagogical alchemy's the best!

Successful learners create, innovate,

Think deeply as self, and groups motivate.

They are citizens who are ethical

Responsible glob'ly and as locals.

In Resistance II, Malcolm identifies some of the dominant forces that his practice resists that include instruction of how to teach, as well as what resources to use in his teaching. Specific authors of pedagogical frameworks are identified including Robert Marzano (Art and Science of Teaching), DI (Direct Instruction), John Fleming (Explicit Instruction), and John Hattie (Visible Learning), and global edu-business Pearson is identified as a provider of teacher resources. Malcolm demonstrates resistance to subscribing to these powers, instead trusting his own professional knowledge and capacity to plan learning that will engage his own class.

Hope II

Cortese: Woman of science and learning.

An alchemist; she is nonconforming.

But how is she privileged? How's she oppressed?

Who benefits from her written address?

Such critical questions must be applied

T'all learning resources that I supply.

From such discussion we learn to reflect,

We learn to interpret with dialect.

Global citizens understand their place,

They know their privilege, their debts they can trace.

When they see injustice they know they can

Reject it as truth, start transformations.

They know when they work with others they can

Be more than workers, be strong citizens.

Be more than themselves, work with love and care

Challenge oppression to make the world fair.

The power'd view curriculum as fixed,

See students as passive, not activists.

They fear fact'ries of capable workers,

Organised peoples who are change makers.

Hope II continues to reveal the purpose of schooling that pedagogical alchemists pursue. Earlier, Malcolm observed the future focused nature of hope. In Hope II, Malcolm further reveals his aims to develop students understanding their place as activist global citizens. Pedagogical alchemy students recognise their own privilege and oppression, but then to "be more than themselves", rejecting injustice and transforming the world, as "organised peoples who are change makers." The approach to curriculum that Malcolm proposes in Hope II is a response to the challenge posed by Michael Apple (2013b) Can education change society? and it is a representation of a type of radical and critical pedagogy proposed by McLaren (2007). Apple (2013b) rejects romantic notions of education leading to change, and asserts that only through a concerted act of solidarity and struggle can there be hope for change. Peter McLaren offers,

Critical educators are in the process of creating their own dreams of a world that is arching towards social and economic justice and can see those dreams reflected in the mirror of Freire's dream, one that is inspired by a hope born out of political struggle and a belief in the ability of the oppressed to transform the world from 'what is' to 'what it could be', to reimagine, re-enchant, and recreate the world rather than adopt to it. (McLaren, 2007, pp. 302-3).

Joy III

Be it led to gold, or water to wine,

Creating joy in neo-lib'ral time.

Transformative philosophers know

A grasp of science with self is the go.

To truly acquire alchemy's secrets,

Pseudo-Democritus says the trick is,

Integrate physika kai mystika

(That's science or nat'ral, with the secret).

In education that might even be

Evidence-based data, but used lightly.

Collecting data on student progress

Thought through by teachers' collegial process.

Joy is valuing multiple voices

And trusting teachers' profession'l choices.

Alchemy adds the exoteric world

Esoteric practice with data furled.

And let's not rule out the joy of surprise

Secreti, mystika learning excites.

Discovery. Play. Fidgeting around

Allows personal meaning to be found.

In writing about Joy, Malcolm describes his own reflections of joy as a teacher, first by writing about discovering Isabella Cortese's I secreti de la signora, then, in Joy II, by the joy that his cognitive verbs attempt to inspire in his classes. In Joy III, Malcolm considers a role that data could play in pedagogical alchemy when it is used to support collegial processes, as opposed to being privileged in teacher practice. Malcolm attributes this synergy to Pseudo-Democritus' notion of "physika kai mystika", that he translates as natural and secret. Martelli (2013) notes that Pseudo-Democritus was a Greek philosopher and alchemist, whose work pre-dates Isabella Cortese by around 1500 years. As a pedagogical alchemist, Malcolm has an understanding of data related to student progress, and he uses this science to inform his teaching. However, he rejects pedagogy that shifts his practice from a joyful experience of teaching and learning towards experience that creates data for data's sake.

Hope III

You know what hope is? It's a better way,

Making tomorrow better than today.

So we have to dream, have to imagine,

From this standpoint, our practice is fashioned.

We work in a school somewhere on the globe

And we ought to look towards UNESCO,

Whose goals and targets on education

Usurp agendas of corporations.

Together we're working to change futures:

Be more than Their labour or consumers,

Understanding moral obligations,

To improve living in every nation.

Education, it's UNESCO's goal four:

Seeks learning opportunities for all.

Gender equity, it's universal

Pre-primary, then primary, through to high school.

Quality learning, that's equitable,

Youth literacy, again: universal,

Vocat'nal skills for a decent earning,

Opportunities for lifelong learning.

Malcolm's three quatrains about hope develop from curriculum experiences that are future focused, in Hope I, and that position young people as activist local and global citizens, in Hope II. In Hope III, Malcolm positions education as future focused and locates his practice in the global context of UNESCO's goals for sustainable development. UNESCO's fourth goal is to "ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all" (UNESCO, 2015). In his final writing on hope, Malcolm interprets the intent of UNESCO's goal for education as being to improve equity of access to education, and to improve living conditions, rather than reducing education to merely benefit "Their labour or consumers". He does acknowledge the goal includes references to training vocational skills, however this ought to support target 4.4 that seeks "Relevant skills for decent work" (UNESCO, 2015).

Responding to Wrigley's call to rethink education, the purpose of this paper has been to build community by giving voice to the practice of pedagogical alchemy. That said, I recognise the hazards that alchemists face as they resist dominant forces in the pursuit of joy and hope. To that end, I offer Malcolm's final quatrain as an epilogue to this chapter. As Isabella Cortese might have requested readers of her own book, I recognise the risks of our work, and end with a message to my fellow pedagogical alchemists.

Resistance III

Dear Craig, and your researcher-writer's voice,

Here's a caution from Malcolm's teacher voice.

There's a danger inherent in this piece,

Interpreting story, uncritically.

"See, it's true," powerful voices might claim,

"Look at his classes, his teaching maintains

Quality teaching, quality results.

All that's needed is quality adults."

This sets up Their view, that teaching's to blame

For declining standards in PISA's game.

That's not why I speak up, nor why you write,

Don't let my quatrains embolden their fight.

Which teachers replicate privilege in youth?

Teachers measured 'gainst Their singular truths

They want curriculum hegemony

Dominant, fundament'list zealotry.

My caution's this, in my final quatrain,

Power wants dominant voices maintained.

So, friends, I ask, like Cortese' request

Burn these quatrains when you've learned their secrets.

References

Adams, T.E., Holman-Jones, S., & Ellis, C. (2015). Autoethnography: Understanding qualitative research. Oxford University.

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). (2022a). Australian Curriculum: History https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/humanities-and-social-sciences/history/

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). (2022b). Australian Curriculum. https://www.scootle.edu.au/ec/search?accContentId=ACDSEH056

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). (2022c). Australian Curriculum. https://www.scootle.edu.au/ec/search?accContentId=ACDSEH058

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). (2022d). Australian Curriculum. https://www.scootle.edu.au/ec/search?accContentId=ACDSEH010

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). (2022e). Australian Curriculum. https://www.scootle.edu.au/ec/search?accContentId=ACDSEH057

Apple, M. (2013a). Educating the "right" way: Markets, standards, God and inequality (2nd Ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203112847

Apple, M.W. (2013b). Can education change society? Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203083550

Apple, M.W. (2017). What is present and absent in critical analyses of neoliberalism in education. Peabody Journal of Education, 92(1), 148-153. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2016.1265344

Australian Government. (2016). Quality schools, quality outcomes. https://docs.education.gov.au/documents/quality-schools-quality-outcomes

Babalola, N. S. (2015). Curriculum orientations of K-12 virtual teachers in Kansas. GSTF Journal on Education 3(1) pp 17-28. https://doi.org/10.5176/2345-7163_3.1.65

Baltodano, M. (2012). Neoliberalism and the demise of public education: The corporatization of schools of education. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 25(4), 487-507. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2012.673025

Berry, J. (2016). Teachers undefeated: How global education reform has failed to crush the spirit of educators. Trentham Books.

Biesta, G. J. (2015). Beautiful risk of education. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315635866

Bloom, B.S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives. Longman.

Bochner, A. (2014). Coming to narrative: A personal history of paradigm change in the human sciences. Left Coast Press.

Bolton, G. (2014). Reflective practice: Writing and professional development (4th ed.). Sage Publishing.

Boylorn, R.M., Orbe, M.P. (2014). Critical autoethnography as method of choice. In R.M. Boylorn, M.P. Orbe (Eds.). Critical autoethnography: Intersecting cultural identities in everyday life (pp. 13-26). Left Coast Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315431253

Brookfield, S.D. (2017). Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Clough, P. (2002). Narratives and fictions in educational research. Open University Press.

Connell, R. (2013). The neoliberal cascade and education: an essay on the market agenda and its consequences. Critical Studies in Education 54(2) pp 99-112. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2013.776990

Cortese, I. (1565). I Secreti de la Signora Isabella Cortese. https://openlibrary.org/books/OL24444521M/I_secreti_de_la_signora_Isabella_Cortese

Crowther, F., & Boyne, K. (2016). Energising teaching: The power of your unique pedagogical gift. ACER.

Daniels, E. (2010). Fighting, loving, teaching: An exploration of hope, armed love and critical pedagogies in urban teachers' praxis (Doctoral thesis, University of Rochester, Rochester, USA). http://search.proquest.com.libraryproxy.griffith.edu.au/docview/521953157?accountlist=14543

Denzin, N.K. (2014). Interpretive autoethnography (2nd ed.). Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781506374697

Denzin, N.K. (2018). Performance autoethnography: Critical pedagogy and the politics of culture. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315159270

Department of Education, Skills, and Employment. (2019). The Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration. https://www.dese.gov.au/alice-springs-mparntwe-education-declaration/resources/alice-springs-mparntwe-education-declaration

Eisner, E.W., & Vallance, E. (1974). Conflicting conceptions of curriculum. McCutchan.

Ellis, C. (2004). Ethnographic I: A methodological novel about autoethnography. Alta Mira.

Ellis, C. (2009). Revision: Autoethnographic reflections on life and work. Left Coast Press.

Evers, J., & Kneyber, R. (2016). Introduction. In J. Evers, R. Kneyber (Eds.). Flip the System: Changing education from the ground up (pp 1-7). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315678573-1

Fickel, L. H., Macfarlane, S., & Macfarlane, A. H. (2017). Culturally responsive practice for indigenous contexts: Provenance to potential. In Global Teaching (pp. 101-127). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-52526-0_6

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Herder and Herder.

Freire, P. (1993). Pedagogy of the city. Continuum.

Freire, P. (1994). Pedagogy of hope: Reliving pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum Publishing Company.

Giroux, H.A. (2011). On critical pedagogy. Bloomsbury.

Hill, D. (2010). Class, capital and education in this neoliberal and neoconservative period. In S Macrine, P. McLaren, D. Hill (Eds.). Revolutionizing pedagogy: Education for social justice within and beyond global neoliberalism (pp 119-144). Palgrave MacMillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230104709_6

hook, b. (1994). Teaching to Transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. Routledge.

hook, b. (2003). Teaching community: A pedagogy of hope. Routledge.

Iosefo, F., & Iosefo, J. (2020). Hear, here you're naked truth. Departures in Critical Qualitative Research, 9(2), 62-71. https://doi.org/10.1525/dcqr.2020.9.2.62

Kendall, J.S., & Marzano, R.J. (2006). The New Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Hawker Brownlow Education.

Kincheloe, J. (1991). Teachers as Researchers: Qualitative inquiry as a path to empowerment. Falmer Press.

Kress, T.M. (2011). Critical praxis research: Breathing new life into research methods for teachers. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-1790-9

Leavy, P. (2013). Fiction as research practice: Short stories, novellas and novels. Left Coast Press.

Leggo, C. (2012) Sailing in a concrete boat: A teacher's journey. Sense Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6091-955-8

Lewis, T.E. (2015), Suspending the ontology of effectiveness in education: Reclaiming the theatrical gestures of the ineffective teacher. In T. Lewis, M. Laverty (Eds.). Art's teachings, teaching's art: Contemporary philosophies and theories in education (pp. 165-178). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-7191-7_12

Lewis, S., Savage, G.C., & Holloway, J. (2020) Standards without standardisation? Assembling standards-based reforms in Australian and US schooling, Journal of Education Policy, 35(6), 737-764. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2019.1636140

Mackinlay, E. (2019). Critical writing for embodied approaches: Auteothnography, feminism and decoloniality. Palgrave McMillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-04669-9

Marzano, R.J. (2007). The art and science of teaching: A comprehensive framework for effective instruction. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Marsh, C.J. (2009). Key concepts for understanding curriculum (4th ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203870457

Martelli, M. (2013). The four books of pseudo-democritus. Maney Publishing.

McLaren, P. (2005). Critical pedagogy and class struggle in the age of neoliberal globalization: Notes from history's underside. The International Journal of Inclusive Democracy 2(1).

McLaren, P. (2007). The future of the past: Reflections on the present state of empire and pedagogy. In P. McLaren, J.L. Kincheloe (Eds). Critical Pedagogy: Where are we now? (pp. 289-314). Peter Lang Publishing.

Mitchie, G. (2012). We don't need another hero: Struggle, hope, and possibility in the age of high-stakes schooling. Teachers College Press.

Nordtveit, B. H. (2016). Teaching in adversity. Schools as Protection? Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-25651-1

Olson, K. (2009). Wounded by school: Recapturing the joy in learning and standing up to old school culture. Teachers College Press.

Parkes, R.J. (2013). Challenges for curriculum leadership in contemporary teacher education. Australian Journal of Teacher Education 38(7), 112-128. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2013v38n7.8

Pelias, R.J. (2016). If the truth be told: Accounts in literary forms. Sense Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6300-456-5

Pelias, R.J. (2019). The creative qualitative researcher: Writing that makes readers want to read. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429057380

Pinar, W.F. (2012). What is curriculum theory? (2nd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203836033

Poulos, C.N. (2021). Essentials of autoethnography. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000222-001

Queensland Government. (2015). School planning, reviewing and reporting cycle. http://education.qld.gov.au/stratgeic/accountability/performance/sprrf.html

Renner, A. (2009). Teaching community, praxis, and courage: A foundations pedagogy of hope and humanism. Educational Studies 45(1), 59-79. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131940802527209

Rizvi, F., Lingard, B., & Rinne, R. (2022) Reimagining globalisation and education: An introduction. In F. Rizvi, B. Lingard, R. Rinne (Eds.). Reimagining globalisation and education (pp. 1-10). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003207528

Sahlberg, P. (2016). The global education reform movement and its impact on schooling. In K. Mundy, A. Green, B. Lingard, & A. Verger (Eds.). The handbook of global education policy (pp. 128-144). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118468005.ch7

Spry, T. (2016). Autoethnography and the other: Unsettling power through utopian performatives. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315545356

Theopedia. (2016). Joy. www.theopedia.com/joy

Tripp, D. (2012). Critical incidents in teaching: Developing professional judgement. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203802014

UNESCO. (2015). Sustainable development goal 4 and its targets. https://en.unesco.org/node/265600

Upshaw, A. (2017). My body knows things: Black women's stories, theories, and performative autoethnography. In D.M. Bolen, S.L. Pensoneau-Conway, & T.E. Adams (Eds.), Doing autoethnography (pp. 55-65). Sense Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6351-158-2_7

Wood, C. (2018). The last days of education: An attempt to reclaim the teaching profession through Socratic dialogue. In S. Holman-Jones, M Pruyc (Eds.). Creative selves / creative cultures: Critical autoethnography, performance and pedagogy. Palgrave McMillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47527-1_9

Wrigley, T. (2006). Another school is possible. Trentham Books.