So what? Can we learn anything about university teaching from jazz?

Chris Hall1

1Swansea University, Swansea, UK

Abstract

This paper examines whether teachers in universities can learn from the practices and structures of jazz music as they try to prepare students for an uncertain future. It outlines the fundamental characteristics of jazz and how these have been applied by jazz musicians. The paper focuses on four of the building blocks of jazz: improvisation, mistakes, collaboration and leadership, and examines how these translate to university teaching. It concludes that effective learning, like the best jazz, is collaborative and occurs where the freedom to improvise and make mistakes is integral. Additionally, as with the best jazz bands, there must be some structure where the teacher, although leading, is fully involved in the collaborative act of discovery with the learners. The author argues that the lessons learned from jazz should be incorporated in professional development programmes for new university teachers.

Keywords

jazz, teaching, pedagogy, improvisation, learning outcomes,

professional development

Introduction

We are living in an increasingly uncertain world. A world of shifting borders (Shachar & Fine, 2020); rapid technological change; increasing fluidity of identity; even changes in what constitutes life and what it means to be human (Bokedal et al., 2022). A future for which we don’t necessarily have neat answers. How should we prepare students for a world where the future is seemingly so uncertain?

This paper explores using jazz as a metaphor for university teaching in this context. It will focus on four key, interconnected areas of jazz – improvisation, mistakes, collaboration, and leadership – and argue that by incorporating these aspects of jazz into their teaching, university teachers can better enable students to survive and adapt in this uncertain future. While the improvisational element of jazz has previously been explored as a metaphor for teaching by Montuori (1996) and Mills (2009), this paper will attempt to show that by adopting these four key areas of jazz, a teacher can enhance both their own way of being a teacher and the organisational structures of their teaching.

So, what does jazz music have to do with the serious business of a university education? Plato maintained that music is training for the mind (Plato, 2015) and that music was the most important subject to teach as it underpinned all other learning. He is even reputed to have said, “I would teach children music, physics and philosophy; but most importantly music, for in the patterns of music and all the arts are the keys of learning.” (Farokhi & Hashemi, 2011 p. 926). By the twentieth century, philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein argued that musicians were only valued as entertainers. “People nowadays think scientists are there to instruct them, poets, musicians, etc. to entertain them. That the latter have something to teach them, that never occurs to them” (Wittgenstein, 1998, p. 38e).

A former language teacher, I now work in the central teaching support unit of a research-intensive UK university. I am the Programme Director for the University’s Post Graduate Certificate in Teaching in Higher Education (PG Cert HE) as well as the Programme Manager for routes to Fellowship accredited by Advance HE. I am also the trumpet player and bandleader with jazz electronica act ‘no false lemmas’. I see similarities and contradictions between these two worlds. The creativity, the flexibility, the restrictions, the setting off on a journey that you don’t know where it will end, the complexity, the simplicity, the codification, the measurement, the standardisation, the structure, the freedom, the freedom within structure... I will leave you to reflect on which applies to which as you read the paper. From my experience of both worlds, I feel that Higher Education has much to learn from the way that improvisation, mistakes, collaboration, and leadership are approached in jazz.

So what is jazz? Improvisation?[1]

Before exploring whether teachers in higher education can learn anything from Jazz, we first need to attempt to define what jazz is. So, what is jazz? This is a very difficult question to answer and one that with the wrong person can get you into a never-ending argument. In fact, some people are keener on defining what’s not jazz; often music they don’t like. Is it America’s classical music? Is it about syncopated rhythms? Must it have polyphonic ensemble playing? Is it always acoustic? Can it never be electric? Is it music for the old or the young? For listening or for dancing? Is it museum music or the most creative art of all? Does it mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing? All of the above are likely to be contested by somebody but there seems to be one element that most would agree is key to jazz and that is improvisation (Coker, 1987); musicians creating and performing at the same time; spontaneous, in the moment creation and performance.

Improvisation is not something that is a key element of modern classical music, where musicians interpret the score by the way they play the notes written by the composer. However, this has not always been the case. Amongst others, Bach, Mozart and Beethoven were well known for their improvisation. As the Baron de Tremont is quoted as saying,

I fancy that to these improvisations of Beethoven’s I owe my most vivid musical impressions. I maintain that unless one has heard him improvise well and quite at ease, one can but imperfectly appreciate the vast scope of his genius. (Prod'homme & Baker, 1920 p. 376)

Since the time of Bach, Mozart and Beethoven classical music has changed, as have universities. A modern university is much like a modern orchestra with the conductor/Vice-Chancellor at the top and everyone else in their place playing their part from the score/university policy and procedure/learning outcomes in order to, “manufacture high-quality, multi-skilled units of human capacity” (Collini, 2012 p. 132). This fits with the Command and Control, Scientific Management of Taylorism (Taylor, 2018), and the factory processes that have seen a resurgence in recent years (Kantor & Streitfeld, 2015).

Taylor argued that each part of the work done by an individual worker should be analysed 'scientifically'. From this analysis, the most efficient method for undertaking the job is devised; the 'one best way' of working. He also stipulated that there should be a clear 'division' of work between management and workers. Managers should be in charge of planning and supervision, while workers are there to carry the work out.

He explained it thus:

Under the management of 'initiative and incentive' practically the whole problem is 'up to the workman' while under the scientific management fully one-half of the problem is 'up to the management'. Perhaps the most prominent single element in modern scientific management is the task idea. The work of every workman is fully planned out by the management at least one day in advance, and each man receives in most cases complete written instructions, describing in detail the task which he is to accomplish, as well as the means to be used in doing the work. (Taylor, 2018, p. 20)

So, we have each person in their place carrying out the role that has been allotted to them. All managed and measured by checks and balances, exams, tests, module evaluations, Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) and performance reviews.

As well as fitting the command and control format outlined above, modern orchestras generally repeat what has been before with a tried and tested repertoire fuelled by “classical music's idolatrous relationship with the past” (Ross, 2010, para. 8). Again, it can be argued that Universities are similar in the way that they teach, with exams and assignments that test what students have heard in lectures and seminars. Information transmitted in a lecture, written down and ‘performed’ by the students in an exam or assignment. (The recent ‘Moral Panic’ over AI written essays, suggests that this ‘performance’ is perhaps still the dominant form of assessment in the UK). This approach, coupled with the massification of higher education and the attempt to use ever larger teaching groups in effort to take advantage of perceived economies of scale, could well be exacerbated in the post pandemic era. Journalistic opinion pieces, such as that by Prof. Peter Dolton of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, who argued that post pandemic, “People all over the world can learn and teach to huge audiences at close to zero marginal cost” (Dolton, 2020, para. 3) provide inspiration to university management to look at the use of learning technology, when in person teaching was not possible, and see a conceivable future where they can increase student numbers and reduce costs. One area often highlighted by Vice Chancellors (Doughty, 2021) is the move to mass online exams, which the Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC) argues need to be automated, continuous and contain “authoring detection and biometric authentication adopted for identification and remote proctoring” (JISC, 2020, para. 9). In essence, large-scale, controlled and tested. One would imagine Taylor would approve.

So should we just let it all hang out?

If the modern university is like a highly managed orchestra where improvisation is absent, how could improvisation become part of teaching? Should Higher Education be a world where there are no rules and everyone is free to improvise; to learn and teach in whatever way suits them at a given moment?

Illich argued for a Deschooling Society. A world where education would be free and open. According to Illich society should,

Provide all who want to learn with access to available resources at any time in their lives; empower all who want to share what they know to find those who want to learn it from them; and, finally furnish all who want to present an issue to the public with the opportunity to make their challenge known. (Illich, 1971 p. 78)

This openness was an influence on the original Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) put forward by Downes and Siemens (Siemens, 2005). These MOOCs were based on Downes and Siemens theory of Connectivism, where “the starting point for learning occurs when knowledge is actuated through the process of a learner connecting to and feeding information into a learning community” (Kop & Hill, 2008 p. 2). This approach shouldn’t be confused with the Silicon Valley/Venture Capital MOOCs of Coursera, Ed Ex and the like. (Armstrong 2012). The original cMOOCs, as Downes and Siemens referred to them, had great freedom for the learners to explore the subject. Some learners can cope with this level of freedom and thrive on the ability to wander around a subject, learn what they want to, when they want to. As learners, they are able to improvise freely without imposed rules or structure. However, not all learners can do this, in the same way that in jazz not everyone is noted saxophonist Charlie Parker with a heightened ability to move away from the structures of previous generations (Williams, 1993).

In cMOOCs the control of learning “no longer rests with an educational institution but with the learners themselves” (Fournier, Kop & Durand, 2014 p. 2). As a result, many learners can struggle in this kind of environment without the help of knowledgeable others (Kop, 2011). Dropout rates are also extremely high, with retention rates much lower than for more traditional online courses (Alraimi, Zo and Ciganek, 2015). It can be argued that far from opening up education, this type of freedom only benefits those who already have the necessary skills and attributes of an independent learner; narrowing rather than widening participation (Caulfield, 2012).

So what should we do about improvisation?

If

the answer is not the ‘command and control’ of the classical orchestra but not

‘free jazz’ either, what should the approach to improvisation be? Although the

term is often connected with music, Nachmanovitch argues the arts that are

associated with improvisation are “doors into an experience that constitutes

the whole of everyday life” and that we are all improvisers (Nachmanovitch,

1990 p. 17). He argues that ordinary speech is the most common form of

improvisation. Although we talk and listen using the vocabulary and grammar

handed down by our culture, we can use this vocabulary and grammar to create

sentences that may never have been heard before.

If

the answer is not the ‘command and control’ of the classical orchestra but not

‘free jazz’ either, what should the approach to improvisation be? Although the

term is often connected with music, Nachmanovitch argues the arts that are

associated with improvisation are “doors into an experience that constitutes

the whole of everyday life” and that we are all improvisers (Nachmanovitch,

1990 p. 17). He argues that ordinary speech is the most common form of

improvisation. Although we talk and listen using the vocabulary and grammar

handed down by our culture, we can use this vocabulary and grammar to create

sentences that may never have been heard before.

Much of Jazz improvisation is based on the vocabulary and grammar of scales (a set of musical notes ordered by frequency or pitch) and chords (a set of 3 or more notes played at the same time). At its most basic, it is a blues scale played over a 12 bar blues. Bars being small sections of music containing a set number of beats, usually 4 in blues. The blues was one of the most important ingredients that contributed to the birth of jazz in New Orleans at the turn of the 20th Century (Gioia, 2016).

At a very basic level, as the 12 bar blues is played through, a soloist could play notes from the blues scale over the top to improvise a melody. Once you have learnt the structure of the blues scale you can apply it to a blues scale in a different key. So, if the band play a 12 bar blues in the key of E, you’ll know what the chords are and that starting on E you will know what the notes of the blues scale in E will be.

The blues scale is very exciting for a new improviser but its limitations can make it pale after a while. Over time, jazz has developed more advanced scales and chord structures that allow greater scope for improvisation, such as changing scales as the chords change - known as ‘playing the changes’, adding new notes to the chords and even loosening the strict relationship between scales and chords. As a jazz musician develops, this knowledge of chords and scales helps them improvise over a song that they have never heard before. Bruner talked of non-specific transfer and the transfer of principles and attitudes. He argued that, “A good theory is a vehicle not only for understanding a phenomenon now but also for remembering it tomorrow” (Bruner 1963 p. 25). In a jazz context, this starts with understanding chord structures and scales and initially applying them to one song but then being able to use this knowledge for any song the musician encounters.

Bruner applied the transfer of principles and attitudes to what he termed the Spiral Curriculum arguing that, “We begin with the hypothesis that any subject can be taught effectively in some intellectually honest form… at any stage of development.” (Bruner 1963 p. 33) In jazz, as your understanding of the relationship between chords and scales develops, you can return to songs previously played and delve deeper; much as Charlie Parker did with the advent of Bebop (Crouch, 2014).

So how does this improvisation work in teaching?

I’ve discussed the need for structure, the freedom to improvise within that structure and also the need to move beyond the structure and delve deeper. Sawyer argues that creative teaching is ‘disciplined improvisation because it occurs with board structure and frameworks’; much like the chords and scales of jazz (Sawyer, 2004 p. 13).

This creativity means the freedom for the teacher and learners to go beyond the structure when required; freedom from the structure of a linear PowerPoint or lesson plan. The freedom to go off track and go where the enquiry takes the class. Socrates records Plato as arguing that, we should let “our destination be decided by the winds of the discussion.” (Plato, 1994 p. 90). This is often referred to as ‘contingent’ or ‘responsive’ teaching, “the calibrated support the teacher provides through interaction with a student” (Broza & Kolikant 2015 p. 1094). This approach can be applied to a whole class. An example of this type of contingent teaching is the method outlined by Steve Draper in a JISC report, where the lecturer can come into a session,

[…] with a bank of diagnostic questions, and use the student answers to those questions to home in on what that audience needs to spend time on now. So that gets away from a fixed script for a lecture, and makes it contingent – that is, dependent on what that audience needs that day. (JISC 2005)

In terms of delving deeper into a subject, in the way that Charlie Parker did with Be Bop and Bruner advocates with a spiral curriculum, we can take second language learning as an example. In the early stages of learning a second language, a learner will often be taught grammatical structures and encouraged to build their own sentences with the grammatical structure outlined by the teacher. However, as their understanding of the language develops, they return to these structures and learn that they are more nuanced and perhaps not the hard and fast rules that had previously been taught or understood.

However, this improvisatory style is a challenge for many new teachers. Kugel (1993) suggests that early career teaches often talk too fast, much like early improvisors who often play too many notes when they start improvising. However, as teachers become more experienced, they begin to improvise more (Borko & Livingston ,1989). This is because as they become more used to the structures and frameworks they use, they are more able to adapt them, deviate from them or change them as the need arises or, as Borko and Livingston describe it, “‘novices’ cognitive schemata are less elaborate, interconnected, and accessible than experts” and that their “pedagogical reasoning skills are less well developed.” (Borko & Livingston, 1989 p. 491) In other words, they don’t yet know their chords and scales well enough and are less able to ‘play the changes’ and improvise effectively. As a result, there is a tendency for early career teachers to stick rigidly to a lesson plan and it's only as experience develops that they are able to be more flexible and improvise in the classroom. Therefore, new teachers should be supported in this improvisation and encouraged not to stick too closely too lesson plans. This issue should be included in Continuing Professional Development (CPD) programmes for new teachers, where they can be given the opportunity to observe experienced ‘improvisers’ in practice and explore how they can improvise themselves. How this observing of others could be approached will be explored in the discussion on leadership later in the paper.

So what about improvising Learning Outcomes?

Learning Outcomes in universities are almost universally based on Bloom’s Taxonomy to the extent that Blooms Taxonomy “has garnered almost dogmatic acceptance in the educational establishment” (Bertucio, 2017 p. 479).

Guidance on creating learning outcomes abounds, often with helpful pyramids and strings of useful verbs, all handily linked to Frameworks for Higher Education Qualifications (FHEQ) levels, with ‘creating’ listed as ‘higher order thinking’ and reserved for post graduate study. These are often accompanied by advice to ensure that ‘good’ Learning Outcomes are SMART - Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic and Time-Bound. Again, Taylor would surely have approved of such outcomes designed by ‘management’ for the ‘workers’ to carry out. This approach leads to education where ‘Contemplation, wonder, appreciation, or merely sitting with an object of study are dismissed as a waste of precious instructional time.’ (Bertucio, 2017 p. 495) and there is no place for improvisation.

Improvising should therefore also mean freedom from these standard learning outcomes, which state that ‘at the end of this module you will be able to X”, which will then be tested to provide a number. How does anyone know that at the end of a module a learner will be able to do X? There are a whole series of reasons why this might not be the case - the learners might not be very interested in the subject and are only there because they have to take it as a compulsory module; the teacher might teach in a way that doesn’t engage the learners particularly well; the course may have been taught in a very cold or hot building that made learning extremely difficult; and so on and so on. These traditional learning outcomes are perhaps at best teaching aspirations, or maybe the score, with little scope for improvisation or for the learner to define what they hope to gain from the experience; what the learner’s intended learning outcomes are. Instead, referring back to Plato’s idea of letting the “destination be decided by the winds of the discussion”, one could say, ‘This module will explore…’ where the explanation gives a broad outline of the areas that the module will cover but does not restrict it within boundaries. The chords and scales to be used but not the prescribed melody to be played. This would enable the class as a whole the freedom to explore the subject and to take them where their inquisitiveness leads, within the ‘chords and scales’ outlined by the teacher; to collectively create a ‘melody’ that is appropriate for that class. Seymour Papert refers to this as creating the conditions for discovery (Papert 1980), which he sees as the teacher’s main role.

One could argue that while this may all seem very straightforward, how could qualifications be awarded if the module or lecture could go off in a variety of directions and not stick to teaching to traditional learning outcomes? In order to provide the grade that is required in Higher Education, the assessment could become part of the learning outcomes. Or they should perhaps be redefined as Assessment Outcomes. Therefore, one would need to add to module learning outcomes, ‘in order to pass this module you will need to demonstrate Y’, with Y being the basis of the assignment. In this way, there is freedom to explore the subject but learners also know what they need to do in order to demonstrate their knowledge and understanding to achieve the required credits. However, some further refinement would be needed for the learner to identify what they hope to achieve. By adding ‘in order to pass you need to demonstrate Y and in order to pass with merit you need to demonstrate Z’ and so on, the learner could then define their own learning outcomes within these parameters. An individual learner’s learning outcome may be to explore the subject in a particular way and achieve the minimum grade they need for the compulsory module. Or they may wish to explore the material in another way given the context of the cohort and ‘the winds of the discussion’ and achieve the Distinction or First Class pass they wish to aim for. Whichever is the case, the learner has a freedom to define the learning outcomes appropriate to their own circumstances. To some this may seem like a semantic argument but I would suggest that it is a much more honest approach. It is not a free for all with a blank slate for learners to decide whatever they want to do but there is some structure that can be improvised around. Within that structure a learner can define what their own learning outcomes are. They therefore have more ownership of the outcomes and more responsibility for them.

So what about mistakes?

One of the key things in jazz and particularly about learning jazz, is the freedom to make what some might term mistakes. As part of the learning of jazz, Ornette Coleman said, “It was when I found out I could make mistakes that I knew I was on to something.” (Brown 2018, p286).[2] With a Jazz ensemble, an environment is created where musicians stretch themselves, there is no score to keep to and if in reaching for something, a musician doesn’t quite make it, that’s accepted as all part of the process. Listen to the classic Miles Davis album ‘Kind of Blue’ and hear the ‘mistakes’ (Davis, et al. 1959).

So how do mistakes work in teaching?

In teaching terms, this acceptance of mistakes has also been referred to in learning as mistakability (Maodzwa-Taruvinga 2016). For example, language learners need to feel comfortable enough to speak and sometimes get things wrong. If there was no room for mistakes, most language learners may never say anything. This can apply to a wide range of areas, including assignments. If a learner strives for something in an assignment and does not make it, following the jazz analogy, there should be no penalty. What is important is what they have learnt in the endeavour and there should be space in the assignment for this to be captured. As in jazz, it should be part of the process.

This could work in practice by using a dialogic approach to feedback. Nicol (2010) argues that “feedback should be conceptualised as a dialogical and contingent two-way process that involves co-ordinated teacher-student and peer-to-peer interaction as well as active learner engagement.” (Nicol, 2010 p. 503). Nicol bases his work on Laurillard’s 2002 framework, where teacher’s and student’s conceptions are accessible to each other, to enable them to agree a learning or assignment goal and to enable the generation and receipt of feedback in relation to an assignment goal. This is another area where the students can improvise and define their own learning and outcomes.

From the student perspective, traditional written feedback is often ambiguous, too general or vague, too abstract and even cryptic. (Nicol, 2010). Dialogic feedback, on the other hand, is designed to engage the student in the feedback process. This could be by asking students to express a preference for the type of feedback they would like when they hand in the assignment and to identify any areas they would like help with, as McKeachie (2002) cited in Nicol (2010) suggests. The students initiate the dialogue as they hand in their assignments and, in requesting feedback, students engage in reflection before comments are received. The dialogue is continued by the teachers as they give feedback, where the teacher can also ask further questions.

This dialogic approach could continue where the assignments build throughout the programme. Each piece of work submitted by a learner being built on reflections on those that they have previously produced. The dialogic approach allows learners to make mistakes and learn from them. Ideally, learners should, as Miles Davis said, “not fear mistakes, there are none” (Nachmanovitch, 1990, p. 88).

So what about collaboration?

As well as improvisation, the other thing that many can agree on is that you can’t play jazz on your own. You need other people to bounce ideas off, to spark your creativity and to learn from. There is only so long you can practice by playing along to play-along backing tracks. As Oscar Peterson is frequently quoted as saying, for example by Furu (2012) in his conclusion to ‘The art of collaborative leadership in jazz bands’, “It's the group sound that's important, even when you're playing a solo. You not only have to know your own instrument, you must know the others and how to back them up at all times. That's jazz” Or as Stan Getz said, “A good quartet… is like a good conversation among friends interacting to each other's ideas” (Martin, 1986, as edited by Joffe, 2020). It’s in this conversation that jazz musicians share a mutually created space where, through improvisation, both when backing the soloist and when soloing themselves, they push and challenge each other to negotiate their way through the song and create more than they could on their own.

So how does collaboration work in teaching?

This is akin to Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development, where a more experienced other can help a learner achieve more than they would on their own (Vygotsky, 1978). However, referring back to Stan Getz’s conversation analogy, it is perhaps closer to Neil Mercer’s Intermental Development Zone (IDZ) (Mercer, 2006). Mercer argues that “the meaning of words are generated in context, through dialogue, and when we speak we almost always do so in partial response to what others have said” (Mercer, 2006 p. 137). His IDZ is a shared communicative space, which is constantly reconstructed as the conversation continues and which the learners must use to negotiate their way through the learning activity. According to Mercer, the conversation must be a genuine conversation and not a series of monologues, for, “if the dialogue fails to keep minds mutually attuned, the IDZ collapses and the scaffolded learning grinds to a halt” (Mercer, 2006 p. 147). Kugel (1993) suggests that early career teachers focus on themselves and what they are doing rather than what the students are doing or the conversation between them, much in the same way that early improvisors listen to themselves and not to the band. If the musicians stop listening to each other, the performance falls apart.

Further support to the power of group collaboration is Moshman and Geil’s work on collaborative reasoning. Here when faced with a logical hypothesis-testing problem only 9% of individuals arrived at the correct answer, whereas 75% of groups did (Moshman & Geil, 1988). They suggest that levels of understanding that are difficult to elicit in individual performance may emerge in the context of collaborative reasoning. Much of their analysis of this collaborative reasoning follows the conversations that took place within the groups. Thus the dialogue is key and as Alfonso Montuori contends, “Improvisation involves a constant dialogic between order and disorder, tradition and innovation, security and risk, the individual and the group and the composition” (Montuori, 2003 p. 246). This importance of dialogue is key to the classroom but, as has already been mentioned, can also play a key role in assessment, with the conversations that occur, for example, in reflection and dialogic feedback allowing learning to come from ‘mistakes’.

Taking the role of dialogic feedback further, Nicol advocated the use of peer dialogic feedback, arguing that when students regularly give feedback on assignments of peers, they develop the ability to recognise what characterises a quality assignment and about different ways it can be produced: they learn that quality does not come in a pre-defined form, rather there are a spectrum of possibilities. (Nicol, 2010).

Er et al (2020) take this further and have outlined a framework to support the scalable use of peer feedback in which “students are placed as learning agents who negotiate meaning from feedback through a dialogue with peers” (Er et al, 2020 p. 595) They advocate the use of rubrics to support students in the reaching of a consensus on the quality of the students work. In effect providing the students with the ‘chords and scales’ of feedback. With these ‘chords and scales’ students can create an agreed conversation space for meaningful feedback to take place in.

So what about leadership?

Although jazz bands are about improvisation and musical conversations, they generally have one person who acts as a leader. Traditionally this was often the person whose name formed the name of the group, such as the Miles Davis Quintet or the Duke Ellington Orchestra. Leading a band adds to the complexity of the musician’s role, as Miles Davis, quoted by Ian Carr, would agree, “You add to playing your instrument the running of a band and you got plenty of problems” (Carr, 2007 p95). Interestingly Miles Davis argued that he didn’t lead in a traditional way. “I don’t lead musicians, man. They lead me. I listen to them and learn what they can do best.” (Santoro, 2018 p. 142).

Gene Santoro argues that Miles Davis leadership style “forces players to be participants in the democratic model we call a jazz combo.” His approach “frees up the horizon and lets – in fact makes – all that work itself out in its own time, along its own dynamic, for each of the individuals involved” (Santoro, 2018 p. 140).

Many of the members of Miles Davis’s various bands went on to lead bands of their own. When Herbie Hancock was asked if he had learned some of his lessons about leading groups from Miles Davis he said, “Absolutely. About teamwork, listening and not being afraid to lean on the band for ideas and direction – allowing space for the band to be part of the direction. Miles never told us what to play, never told us what notes to play” (Santoro, 2018 p. 140).

So how does leadership work in teaching?

For Mercer (2006), the teacher’s role is key in guiding the learners. Here they are acting in a similar role to a jazz bandleader, whether in a Big Band or a small trio. Sawyer argues that one of the key but less widely known attributes of a good teacher is that as well as being an improviser themselves, they need to be able to skilfully manage the group improvisation of the class (Sawyer 2004). Sawyer goes on to describe this as “managing the participatory aspects of social interaction within the class such as turn taking, the timing and sequence of turns, participant roles and relationships, the degree of simultaneity of participation and the rights of participants to speak” (Sawyer, 2004 p. 15). Although Miles Davis says ‘you got plenty of problems’ running a band, this is something that comes with experience, as with knowing your ‘chords and scales’ and moving away from the lesson plan. Similar to improvisation, this should be included in CPD for new teachers, with them being encouraged to observe experienced ‘bandleaders’ in action and supported in developing these skills in their own teaching, in the way that Herbie Hancock did while watching Miles Davis in action. There is significant literature on the value of Peer Observation of teaching, particularly when using the approach outlined by Gosling (2002), where peer observation is reciprocal, based on an equal and dialogic approach. There is also an increasing focus on the value of Peer Observation for the observer. Hendry and Oliver (2012) found that observers benefit from learning about new teaching and learning strategies and are prompted to use these in their own practice. Through observing others, observers can also learn about and reflect on their own practice (Sullivan 2012).

Tenenberg (2016) found that the observer engages in a ‘double-seeing’ of their classroom in comparison to the classroom they are observing. This enables them to notice challenges they face in the class they are observing that are difficult to identify when they themselves are teaching.

Torres et al (2017) argue that a peer observation and collaborative model can be a worthy model to support longitudinal professional conversations and reflection on practice. It’s not just a one-off exercise. It’s something that can be a continuing part of a teacher’s development throughout their career.

Many of the bandleader’s tasks are potentially similar to the classroom management skills of a teacher in compulsory school education. However, the bandleader is not a conductor directing the band from the side. In small combos the leader is clearly a member of the band but in larger ensembles, leaders such as, Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie and Benny Goodman, to name but a few, all played in their Big Bands. They were an active participant in the creation of the music. Similarly, it can be argued that university teaching is at its best when the teacher is fully involved in the collaborative act of discovery with the learners. O’Keeffe et al (2021) found that peer observers learnt things that lead to better student teacher interactions and fostered students’ motivation, engagement and independent learning. This further adds to the collaborative element of the classroom.

So how does this all work in practice?

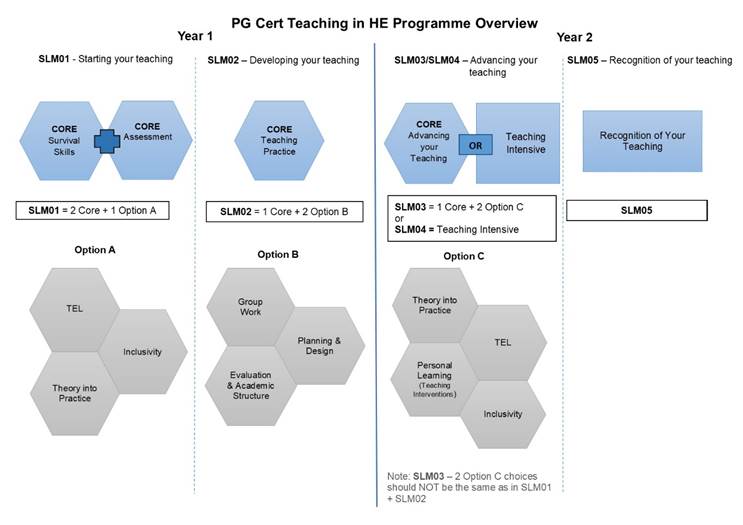

As an example of how this approach might work in practice, I will use the ‘Theory into Practice’ patch, that I run, from a Post Graduate Certificate in Teaching in Higher Education programme for teaching staff at university. It forms part of the first module of the programme and can also be taken as an option in the second year. The programme has a patchwork structure, with a variety of routes for participants to take. Each element of the programme is referred to as a patch with the final module being where participants ‘stich’ all of the patches together and tell the story of the teacher they have become. See Figure 1.

Figure 1. The Patchwork structure of the PGCertHE Programme

Extensive use of peer observation is made throughout the programme using the approach outlined by Gosling (2002), where peer observation is reciprocal, based on an equal and dialogic approach. During observations, the observee is never judged on their teaching. If mistakes are made, they are all part of their learning experience. It’s the observee’s reflections on the experience that form the assessment component.

The Theory into Practice patch explores knowledge from a philosophical perspective and also theories of learning. The patch begins with the following statement on the Virtual Learning Environment (VLE):

For this patch we'll be adopting the following metaphorical approach after the American Philosopher William James. We’ll be visiting a corridor with a number of rooms. Inside the rooms technicians will be working on a number of interesting and complex problems. We are not going to explore all of the rooms but we can peer into some and see what the technicians are up to. You may of course revisit the corridor at your leisure, spend more time in some of the rooms we have visited and visit some of the other rooms we have not visited.

Additionally, as we travel along the corridor, we'll be taking the following roles:

先生 Sensei (born before) one who has gone before – my role

雲水 Unsui (cloud and water) – truth seeker – your role

I hope you enjoy the journey and return to the corridor often during your teaching career.

The use of the roles is designed to move away from the traditional teacher/student hierarchy. I may be the bandleader but I have a playing role in the band. We are all on a journey of discovery together.

The VLE site is divided into ‘Rooms’ as shown in this extract below in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The ‘Rooms’ structure from the PG Cert tHE Programme

There is a structure suggested in the patch VLE by the rooms but participants are welcome, and indeed encouraged, to choose any route they wish through the material.

In each room there are numerous questions to prompt reflection. These questions form the basis of the discussion at the live sessions, which are led by what has interested the participants. At the start of the patch, I explain that I won’t be giving any answers to the questions. There may in fact be no answers, just further questions.

The Learning Outcomes are made up of an overview of the general direction of the patch, with the assignment rubric used to indicate what participants will need to demonstrate in order to successfully complete the patch.

During the patch you will explore the meaning of knowledge and how that underpins the role of teaching in a university.

In this patch you will have the opportunity to explore a number of theories of learning and examine how they might relate to university teaching and learning.

You will also have the opportunity to reflect on the philosophy and theories explored in order to demonstrate your understanding of them and how you might apply them to your teaching.

In order to successfully complete this patch, you will need to demonstrate a good understanding of the patch material and how it relates to your teaching as outlined in the patch rubric. (Hall, 2023)

As part of the assignment, the participants are asked to complete a cover sheet which asks the three questions below, in order to initiate a dialogic approach to the feedback.

· Which parts of this assignment are you most pleased with?

· Were there any areas you found challenging? If so, please specify.

· Are there elements you’d like feedback on? If so, please specify.

Every iteration of the patch is unique, with various elements interesting and challenging participants in different ways. The conversations are never the same and the assignments cover a wide range, often going well beyond the material included in the patch. Despite their wide range, successful assignments always cover the requirements of the assignment rubric.

However, it should be noted that a small number of students can find aspects of the patch challenging and require a little more support than others in understanding how to navigate the freedoms they have within the structure provided.

So what?

So, to conclude, what can higher education teaching learn from jazz? Referring back to the definition of what jazz is, we have established that although it can take many forms, jazz is first and foremost about improvisation – spontaneous, in the moment creation. However, jazz is about freedom, not anarchy. The best improvisation takes place within a structure and the ability to improvise develops over time, with what some would term mistakes being seen as all part of the process of jazz. You can’t do it on your own but it’s not just about a soloist and a backing band. There needs to be a conversation that is truly collaborative, where people play different roles at different times in order to serve the whole. Nevertheless, someone needs to play the role of bandleader, which requires an additional set of responsibilities and skills, while still remaining an active part of the band. In this environment, jazz can take place that is of benefit to all of the musicians involved as well as any audience.

So, if we are to model teaching on jazz, the key to good teaching is therefore improvisation but not about being completely free form, as this can be especially challenging for some learners. It is about creating a collaborative environment, providing some structure but being able to go in the direction required by the class, within a particular teaching session as well as across a module or course as a whole. Mistakes are part of the process and should not be penalised, even in assessment. It needs to be an environment where learners and teachers play different roles at different times in order to support the learning of the group as a whole. This all needs to be guided but not directed by the teacher to enable collective creation of a ‘melody’ that is appropriate for that class. In this environment, real learning can take place that is of benefit to all of the learners involved.

References

Aebersold, J. (1967). How to play jazz and improvise (Volume 1).

Alraimi, K. M., Zo, H., & Ciganek. A.P. (2015). Understanding the MOOCs continuance: The role of openness and reputation. Computers & Education, 80, 28-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.08.006

Armstrong, L. (2012, August 6). Coursera and MITx - sustaining or disruptive? Changing Higher Education. https://www.changinghighereducation.com/2012/08/coursera-.html

Bertucio, B. (2017) The Cartesian heritage of Bloom’s taxonomy. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 36, 477–497. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-017-9575-2

Bokedal, T., Reindal, S. M., Rise, S., & Wivestad, S. M. (2022). ‘Someone’ versus ‘something’: A reflection on transhumanist values in light of education. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 56(2), 227-237. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9752.12628

Borko, H., & Livingston, C. (1989). Cognition and improvisation: Differences in mathematics instruction by expert and novice teachers. American Educational Research Journal, 26(4), 473-498. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312026004473

Broza, O., & Kolikant,Y. B-D. (2015). Contingent teaching to low-achieving students in mathematics: challenges and potential for scaffolding meaningful learning. ZDM Mathematics Education, 47, 1093-1105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-015-0724-1

Brown, L. B., Goldblatt D., & Gracyk, T. (2018). Jazz and the philosophy of art. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315280615

Bruner, J. (1963). The process of education. Vintage Books. https://doi.org/10.1119/1.1969598

Carr, I. (2007). Miles Davis: The definitive biography. Da Capo Press.

Caulfield, M. (2012, September 1). Why we shouldn't talk MOOCs as meritocracies. Hapgood. https://hapgood.us/2012/09/01/why-we-shouldnt-talk-moocs-as-meritocracies/

Coker, J. (1987). Improvising jazz. Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Collini, S. (2012). What are universities for? Penguin.

Crouch, S. (2014). Kansas City Lightning: The rise and times of Charlie Parker. Harper Collins.

Davis, M., Adderley, J, Kelly, W., Chambers, P., Cobb,J., & Evans, B. (1959). (Kind of Blue) [Album] Columbia Records.

Dolton, P. (2020, June 19). How universities can embrace the post-Covid future. The New Statesman. https://www.newstatesman.com/spotlight/coronavirus/2020/06/how-universities-can-embrace-post-covid-future-1

Doughty, R. (2021, February 16). The future of online learning: the long-term trends accelerated by Covid-19. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2021/feb/16/the-future-of-online-learning-the-long-term-trends-accelerated-by-covid-19

Er, E., Dimitriadis, Y., & Gašević, D. (2020). A collaborative learning approach to dialogic feedback: A theoretical framework. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 46(4), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1786497

Farokhi. M., & Hashemi, M. (2011) The impact/s of using art in English language learning classes. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 31, 923-926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.12.170

Fournier, H., Kop, R., & Durand, G. (2014). Challenges to research in MOOCs. MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 10(1), 1-15. https://jolt.merlot.org/vol10no1/fournier_0314.pdf

Furu, P. (2012). The art of collaborative leadership in jazz bands. In J. Caust. (Ed.), Arts leadership: International case studies. Tilde University Press.

Gioia, T. (2016). How to listen to jazz. Basic Books.

Gosling, D. (2002). Models of peer observation of teaching. Learning and Teaching Support Network Generic Centre. https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/id/eprint/13069/1/gosling.pdf

Hendry, G. D., & Oliver, G. R. (2012). Seeing is believing: The benefits of peer observation. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.53761/1.9.1.7

Hall, C. (2023). SL-M01 Theory into Practice [Course notes].

Hooker, J.L. (1955). Boom Boom [Song] on John Lee Hooker Pointblank.

Illich, I. (1971). Deschooling Society. Marion Boyars.

JISC. (2005). Active collaborative learning - University of Strathclyde. Retrieved April 11, 2019. http://www.elearning.ac.uk/innoprac/practitioner/strathclyde.html

JISC. (2020). The future of assessment: Five principles, five targets for 2025. https://www.jisc.ac.uk/reports/the-future-of-assessment

Kantor, J., & Streitfeld, D. (2015. August 16). Inside Amazon: Wrestling big ideas in a bruising workplace. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/08/16/technology/inside-amazon-wrestling-big-ideas-in-a-bruising-workplace.html

Kop, R., & Hill, A. (2008). Connectivism: Learning theory of the future or vestige of the past? The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 9(3). https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v9i3.523

Kop, R. (2011). The challenges to connectivist learning on open online networks: Learning experiences during a massive open online course. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 12(3): 19-38. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v12i3.882

Kugel, P. (1993). How professors develop as teachers. Studies in Higher Education, 18(3), 315-328. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079312331382241

Maodzwa-Taruvinga, M. (2016). Critical Thinking pedagogy and the citizen scholar in university-based initial teacher education: The promise of twin educational ideals. In D. Hornsby and J. Arvanitakis (Eds.), Universities, the citizen scholar and the future of higher education. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137538697_17

Joffe (2020). Stan Getz Musings (Original work published by Mel Martin in the Saxophone Journal, Winter 1986.) Joffe Woodwinds. https://www.joffewoodwinds.com/articles/stan-getz-musings/

Mercer, N. (2006). Words & minds: How we use language to think together. Routledge.

Mills, M. K. (2009). Using the jazz metaphor to teach the strategic capstone course. In N. Beaumont, (Ed.), ANZAM 2009: Sustainable management and marketing. Melbourne, Australia, 01-04 Dec 2009.

Montuori, A. (1996). The art of transformation: Jazz as a metaphor for education. Holistic Education Review, 9(4), 57-62.

Montuori, A. (2003). The complexity of improvisation and the improvisation of complexity: Social science, art and creativity. Human Relations, 56(2): 237-255. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726703056002893

Moshman, D., & Geil, M. (1988). Collaborative reasoning: Evidence for collective rationality. Thinking and Reasoning, 4(3), 231-248. https://doi.org/10.1080/135467898394148

O’Keeffe, M. Crehan, M., Munro, M., Logan, A., Farrell, A. M., Clarke, E., Flood, M., Ward, M., Andreeva, T., Chris, V. E., Heaney, F., Curran, D., & Clinton, E. (2021). Exploring the role of peer observation of teaching in facilitating cross-institutional professional conversations about teaching and learning. The International Journal for Academic Development, 26(3), 266-278. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2021.1954524

Nachmanovitch, S. (1990). Free play: Improvisation in life and art. Penguin Putnam Inc.

Nicol, D. (2010). From monologue to dialogue: improving written feedback processes in mass higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(5), 501-517. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602931003786559

Papert, S. (1980). Mindstorms: Children, computers, and powerful ideas. Basic Books.

Plato. (2015). Plato: Laws 1 and 2 (1st ed.). Translated by Susan Mayer. Oxford University Press.

Plato. (1994). Republic. Translated by Robin Waterfield. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.5840/ancientphil199414155

Prod'homme, J., & Baker, T. (1920). The Baron de Trémont: Souvenirs of Beethoven and other contemporaries. The Musical Quarterly, 366-391. https://doi.org/10.1093/mq/VI.3.366

Ross, A. (2010, November 28). Why do we hate modern classical music? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/music/2010/nov/28/alex-ross-modern-classical-music

Santoro, G. (2018). Miles Davis: The Enabler, Part 1. In F. Alkyer (Ed.), The Miles Davis Reader (pp. 139-142). Backbeat Books.

Sawyer, R. K. (2004). Creative teaching: Collaborative discussion as disciplined improvisation. Educational Researcher, 33(2), 12-20. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X033002012

Shachar, A., & Fine, S. (2020). The shifting border: Legal cartographies of migration and mobility: Ayelet Shachar in dialogue. Manchester University Press.

Seimens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. International Journal of Instructional Design and Distance Learning, 2(1). http://www.itdl.org/Journal/Jan_05/article01.htm

Staley, O., & Shendruk, A. (2018, October 16). Here’s what the stark gender disparity among top orchestra musicians looks like. Quartz. https://qz.com/work/1393078/orchestras/

Sullivan, P.B., Buckle, A., Nicky, G., & Atkinson, S.H. (2012) Peer observation of teaching as a faculty development tool. BMC Medical Education 12, 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-12-26

Taylor, F. W., (2018). The principles of scientific management. CNPeReading

Tenenberg, J. (2016). Learning through observing peers in practice. Studies in Higher Education, 41(4), 756-773. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.950954

Torres, A. C., Lopes, A., Valente, J. M., & Mouraz, A. (2017). What catches the eye in class observation? Observers’ perspectives in a multidisciplinary peer observation of teaching program. Teaching in Higher Education, 22(7), 822-838. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2017.1301907

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

Williams, M. T. (1993). The jazz tradition. Oxford University Press.

Wittgenstein, Ludwig. (1998). Culture and value. Edited by G.H. von Wright. Translated by Peter Winch.