Studying digital metamorphosis in university pedagogy: A systematic review

Anna Mavroudi1 and Rebekka Wagstaffe1

1 The University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

Abstract

Metamorphosis signifies a profound and progressive transformation in response to a changing environment. Transitioning to online learning enabled the continuity of education offerings during the recent pandemic, while disrupting university teaching. In that context, the aim of this paper is to understand digital metamorphosis in university pedagogy. We performed a systematic literature review which was driven by two seminal theoretical frameworks: Signature Pedagogies and Transformative learning. The selection criteria entailed peer-reviewed empirical journal articles published in educational technology journals with high impact factor articles published between 2020 and 2023 in English focusing on the intersection of emergency remote teaching and higher education.

We analysed 23 articles by asking ‘what’, ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions applied to university teaching using the Signature Pedagogies framework. Furthermore, we analysed the answers to the ‘why’s’ by using the Transformative learning framework targeting the teachers’ viewpoint. Our findings indicate that the digital metamorphosis comprises three constituent elements: (1) introspect our values, beliefs and expectations as educators in relation to the use of learning technologies, (2) re-conceptualise faculty preparedness and competence to teach online and (3) understand digital transformation as opportunity for transformative learning for university teachers. The findings have both theoretical and practical implications that go beyond the pandemic context targeting a better ‘new normal’ in the post-pandemic era.

Keywords

university pedagogy, higher education, signature pedagogies,

transformative learning, digital teaching and learning

Introduction

Despite much recent relevant research work, there still exists a need for additional research operating “more closely at the intersection of educational technology and higher education research” (Bond et al., 2021, p. 17). This can be interpreted as a need for more research that employs theoretical frameworks aimed to capture the nature of university pedagogy. In this regard, the theoretical importance of this study lies in elucidating the epistemology (i.e. how knowledge is generated and transformed) and didactics (i.e. the processes of teaching and learning with the technology) of teaching online in higher education. These two aspects (epistemology and didactics) are fundamental in understanding educational processes that rely on the digital competences of teachers (Bartolomé et al., 2018; Castañeda & Selwyn, 2018).

Over five years have passed since most university teaching transitioned from face-to-face to a virtual online structure as a measure to limit the consequences of the pandemic. Terms such as ‘Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT)’ (Hodges et al., 2020) were coined during this period to denote the immediate actions taken by universities with respect to modify their educational offerings. Several studies on ERT in higher education report that online learning brought about opportunities that promoted student learning, such as flexibility and self-pacing (Adedoyin & Soykan, 2023). However, these opportunities were accompanied by a series of challenges related to technology (technology dependency, technical problems), socio-economic factors, digital competence, and heavy workload (Adedoyin & Soykan, 2023; Watermeyer et al., 2021), among other factors. Recent studies have explored how university teachers experienced ERT, necessitated by the pandemic, focusing on various parameters such as teachers’ readiness to teach online (Scherer et al., 2021), challenges and coping strategies (Al Issa et al., 2022), technology acceptance and adoption (Xu et al., 2021), digital competences, and so on. Furthermore, several systematic literature reviews have pinpointed to the fact that ERT and online teaching are two distinctively different modalities. Key difference between the two modalities is that online teaching is designed and planned purposefully to be enacted in virtual environments while incorporating pedagogical strategies appropriate to the affordances of digital tool/environment used, whereas ERT is implemented by quickly adapting pedagogical strategies that have been associated with face-to-face higher education (e.g. lectures) to the digital/online modality without thorough planning (Rozo & Ramírez-Montoya, 2025). According to a systematic literature review (Otto et al., 2024), online teaching and learning is distinctively different than ERT with respect to careful consideration of learning design and planning which is often associated with a) flexibility of teaching in time and space, b) paying particular attention to teachers’ readiness for the transition to online teaching, and c) digital spaces compatible with students’ daily lives.

Pre-pandemic critical perspectives (Castañeda & Selwyn, 2018) argued on the necessity of making sense of the digitisation in higher education by shifting our attention from technical aspects related to the use of digital technologies to learning-, pedagogical -, and ‘human’ (e.g. affective) aspects. In line with this, research on online learning in higher education has demonstrated that student behaviour, performance, and engagement depend on the underlying learning design and the teacher’s decision-making around it (Nguyen et al., 2017).

Regarding the affective aspect, reviews on online learning during the pandemic (see for example Mishra et al., 2021) emphasise the importance of care and trauma-informed pedagogy. Therefore, they argue that resilience and empathy should be embedded in models of faculty preparedness for online teaching. This suggestion aligns well with the expressed need for a critical re-conceptualization of faculty readiness for online teaching (Cutri & Mena, 2020) that goes beyond a competency-based approach adopting a more humanistic perspective that addresses affective dimensions, identifies disruption, and the professional vulnerability of faculty’s readiness to teach online.

This article argues that the re-conceptualisation of faculty readiness and competence for online teaching can be a leading catalyst for the digital transformation in higher education. A pertinent question is: what constitutes a ‘profound change’ in pedagogical practice (Dorfsman & Horenczyk, 2022) that could potentially lead to transformation? One answer (Tarling & Ng'ambi, 2016) is that it involves pedagogical practices that shift from ‘transmission pedagogies’ (supporting lowest cognitive activities on the Bloom scale, such as understanding, memorizing, and remembering) to ‘transformation pedagogies’ (supporting higher cognitive activities, such as analysis, comparison, creativity, and evaluation).

Taking all the above into consideration, the article proposes that digital transformation in higher education may be meaningfully conceptualised and captured by employing relevant seminal frameworks. To this end, the article employs two frameworks that together provide a more holistic view: a theory that captures what’s, how’s and why’s of the teaching-learning process coupled with a theory to scrutinise the experiences of teachers and students. Specifically, it uses the Signature Pedagogies framework to unravel university didactics and the theory of Transformative Learning that has adult educators as its primary audience (herein, university teachers). The mutual focus of these two theories is on habit of minds (of university teachers herein) and the importance of the hidden curriculum.

Transformative learning

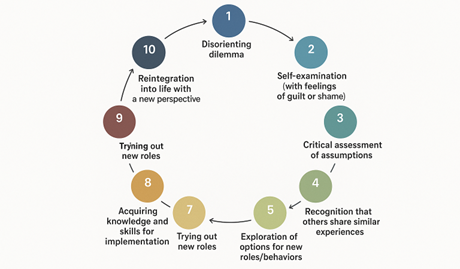

Transformative Learning (TL hereafter) occurs when adults face disorientating dilemmas and transform their frames of reference to make them more inclusive, reflective, and emotionally able to change (Mezirow & Taylor, 2009). These dilemmas might trigger critical self-assessment followed by exploration of options for new roles, relationships, or actions; culminating to trying out (one or more of) these new options, and building competence. Mezirow (1978) originally operationalised TL as a 10-phase model, starting from some disorientating dilemma(s) (phase 1) to exploration of options for new roles, relationships, and actions (phase 5); to provisional trying of new roles (phase 8) leading finally to a reintegration into one’s life (phase 10).

Figure 1. Illustration of Mezirow’s (1978) 10-phase model

Ideally, this process leads to individuals who think globally and critically about their present conditions and decide to act for a change (Kitchenham, 2008). Thus, TL is widely espoused as a principal goal of higher education (Taylor & Cranton, 2012).

Although research focusing on TL for students abides, there is limited research on transformative learning for faculty and their professional development (Bali & Caines, 2018), while a transformation in learning environments in higher education requires that university programs foremost consider how transformation will occur for the university teachers (Bali & Caines, 2018). Therefore, this literature gap has negative impact when it comes to faculty professional development. Other things set aside, teachers’ reflective judgement is much needed in the era of Artificial Intelligence, affecting, among other things, what counts as ‘evidence’ in evidence-based approaches of the ‘what works’ agenda in higher education (Bali & Caines, 2018; Biesta, 2007). The prevalence of apolitical online learning literature (Castañeda & Selwyn, 2018; Öztok, 2019) could also justify the existence of this gap. Yet, there is an increasingly body of relevant literature arguing that online learning is inherently political. Issues mentioned in the literature that might be relevant for this research study include:

· issues of social justice and power structures permeating the hidden curriculum of online learning (Öztok, 2019),

· normalizing Learning Management System use or partnering with commercial providers whose agendas will rarely be centred towards public good (Bali & Caines, 2018),

· “exaggerated claims from commercial providers led many academics to focus on the explicit attributes of a learning technology rather than the inherent pedagogical assumptions, their intrinsic potential and their value” (Salmon, 2014, p. 221)

· measuring faculty readiness for online learning using naive competency-based checklists (Cutri & Mena, 2020).

Furthermore, Bayne (2015) wondered whether instead of asking how technology ‘transforms’ learning we should be asking: what are our values and beliefs as educators and how educational technologies fail to realise our expectations? Teachers’ values, beliefs, and expectations could serve as an appropriate starting point to unpack the digital transformation in higher education.

There are several studies in the context of higher education combining learning technologies and TL theory (Kitchenham, 2006). In their majority, they concentrate on how teachers can foster TL for the students – not on teachers’ own TL. For instance, Alsaywid et al. (2023) discuss pedagogical strategies, assessment and evaluation methods, and faculty development programs that can support students’ TL. In addition, the authors argue on the role of learning technologies in transformative student learning via: enabling access to a wide range of resources, creating immersive and interactive learning environments, and personalising the learning experience. Furthermore, they posit that digital divide/gap and digital literacy are central issues that need to be addressed for TL to occur for (marginalised) students.

Signature pedagogies

The term ‘Signature Pedagogies’ (SP hereafter) was originally used to describe a set of pedagogical strategies ‘historically’ utilised by university teachers to engage students in classroom settings (Friedman, 2023). By ‘historically’, we mean that SP embody teachers’ tacit knowledge on how they can instil the students of the discipline with its content, its skills, and its values. SP are pervasive within particular professions and implicit in the way discipline knowledge is defined, developed, and valued. For instance, teaching mathematics in higher education depends on the use of symbolic and diagrammatic forms for knowledge expression and creation. In turn, this has resulted in pedagogical approaches where handwritten elements have a key role (Maclaren, 2014), ranging from chalk-and-talk teaching to a richer multimodal approach.

SP were originally introduced in the seminal work of Shulman (2005) who described them across three dimensions corresponding to structures of learning environments: surface structure, deep structure, and implicit structure. In the context of this paper, we operationalise them as follows (Dow et al., 2021; Eaton et al., 2017; Shulman, 2005):

· Surface structure is asking ‘what’: what learning looks like and what goes on in the classroom; it involves concrete operational acts of teaching and learning that they are easily observable, such as lectures or case discussions

· Deep structure is asking ‘how’: it involves assumptions about how best to impart knowledge and expertise, teachers’ decisions about how the material will be taught or presented and the advantage of choosing certain pedagogical methods and teaching practices over others. Deep structures are less obvious than surface structures, since they are representations of how a profession fundamentally conceives itself. They can be explicitly articulated or embedded in reinforced or formalised processes such as faculty development programs.

· Implicit structure asks ‘why’: it involves the ‘hidden curriculum’ that includes teachers’ moral dimensions, beliefs about professional attitudes, values, and dispositions, as well as limitations and bounds of learning and application.

Shulman had envisioned converging on a set of SP for teacher education aiming at creating a more coherent professional field, while at the same time avoiding narrow and mechanistic views of effective teaching (Falk, 2006). The idea was that to learn to think like a teacher can mean the same thing in a variety of different teaching contexts. However, these thoughts referred to teacher education for schoolteachers. University teaching is different. For instance, there are no widely accepted professional standards for university teachers, such as those that are widely accepted in the UK, Australia, USA or other parts of the world. Still, in the UK the Professional Standards Framework for teaching and supporting learning in higher education (Advance HE, 2023) emphasises effectiveness and impact, inclusion and the critical role of context. Moreover, the academic disciplines have a more prominent role in university teaching, since “academics at research-intensive universities typically define themselves in relation to their discipline” (Quinlan et al., 2017, p. 62).

Although SP have been primarily used for teaching in higher education within the disciplines, they also have been used across them, focusing on specific sectors of education, such as doctoral education. In their study, Olson & Clark (2009) describe a signature pedagogy in doctoral education that combines theory, applied scholarship, and the wisdom of practice. They describe leader–scholar communities, whose goal was to assist and support students to conduct applied research in local educational contexts.

Another study across disciplines describes the implementation of a course relating to the UDL (Universal Design for Learning) Framework[1]. The course aimed to support teacher students in the use of UDL in their planning to cater for student diversity and the creation of inclusive learning environments. The study had a dual focus since in parallel it described how faculty in the teacher preparation program developed a signature pedagogy rooted on UDL (Reinhardt et al., 2021).

SP can help closing the loop between educational research on how to teach and ‘proper and customary ways’ of teaching in the disciplines (Kelly, 2022). Closing this loop is important since teachers complain that educational theory and research do not align well with the particularities of their classrooms (Brookfield, 1995). Revisiting the ‘chalk-and-talk’ paradigm: it has been criticised for being teacher centric, but at the same time it can be pedagogically interactive, meaningful, and engaging in the context of mathematics education (Maclaren, 2014). In other words, the ‘chalk-and-talk’ approach is a SP in mathematics education because it combines customary with teaching effectiveness. Still, the same approach might be inappropriate in other teaching contexts.

Furthermore, SP have been associated with unintended consequences, e.g. resisting to change while reproducing static curricular methodologies (Dow et al., 2021). Thus, newer teaching approaches (such as online teaching) might struggle as they adapt signatures from face-to-face teaching contexts. SP pushes us to consider the ‘what’, ‘how’, and ‘why’ in higher education. Or, on the opposite side, “we can learn a great deal by examining the SP of a variety of professions and asking how they might improve teaching and learning in professions for which they are not now signatures” (Shulman, 2005, p. 58). This discussion is especially relevant now, because the post-Covid era creates a momentum that higher education institutions should take into consideration, given that the experiences of the main stakeholders (e.g. teachers, students) from the transition to online learning could affect the future of digitisation in higher education (UNESCO, 2021).

Research questions

This article attempts to explore teaching across the three aforementioned structures not by focusing on a subject-specific knowledge base of university teaching, but on a specific sector of university teaching, namely, online teaching. It seems that, although the concept of SP is not new, it is far from being conclusive. We focus specifically on the period of the Covid emergency, in which teaching online became the norm in higher education worldwide due to the necessity of social distancing. Thus, this article aims at problematising the ‘new normal’ of the post-pandemic era. In the context of online teaching in higher education during the pandemic, our research questions are:

1. What were the surface -, deep -, and implicit structures?

2. How was digital transformation manifested (especially in the implicit structures)?

3. What are the ensuing implications for the digital transformation in higher education?

Theoretical framework for unpacking digital transformation

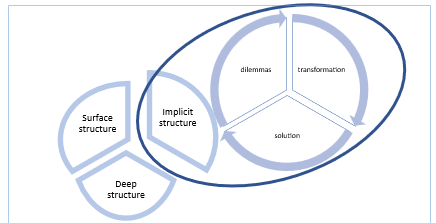

SP is being used herein as a means to unpack digital transformation by employing TL primarily for the teachers and secondarily for the students. The ensuing theoretical framework is depicted in Figure 2. It is the guiding framework for studying research question 2. It presupposes that the digital transformation can be unpacked by combining these two constituent frameworks (SP and TL) and distillate on how they intersect by identifying - mostly at the implicit structure level - disorientating dilemmas and how they were (re)solved.

Figure 2. Theoretical framework for the (digital) transformation in higher education

Relevant work: SP in the context of online learning in higher education

Before the beginning of the pandemic, Eaton et al. (2017) wrote a research report on SP for online learning in higher education. They provided examples that manifest all three types of structures in line with the definitions presented above. Examples of surface structures are: real-time interactions using student response systems (synchronous mode) or learning via a podcast (asynchronous mode) as operational acts of learning. Examples of deep structures include pedagogies like case-based learning or inquiry –based learning. They are selected because both can promote problem solving, higher order thinking, and collaboration among students. Implicit structures are embedded in the design of the online course or environment (i.e. the hidden curriculum); for example, the development of students’ professional attitudes or understanding of the value of formative assessment. Eaton et al. (2017) conclude with a recommendation to choose SP for their effectiveness to build a Community of Inquiry (CoI) that typically comprises three interconnected elements (Garrison et al., 1999): 1) teacher presence, 2) social presence, and 3) cognitive presence. In addition, the authors conclude that there is a gap in the relevant literature with respect to implicit structures in online learning environments.

Another recent example focusing on online education during the pandemic, discusses trauma- informed approaches, such as creating a safe environment and cultivating a sense of belonging (Friedman, 2023). This study ascertained student perceptions via thematic analysis of reflective posts and anecdotal observations. The following four themes emerged: (1) the need to recognise and intentionally discuss the difficulties that students experienced, (2) creating empathic connections and being a compassionate teacher, (3) appreciating faculty availability and flexibility, and (4) clarity of instruction to promote student understanding. These themes can, according to the author, cater for an actionable model for SP embedded in trauma-informed care in graduate health science education. Finally, the article of Parker et al. (2016) investigated whether there are their specific SP that can best effect change in teaching practices and support teacher professional learning. If so, teacher education should benefit from them.

Method

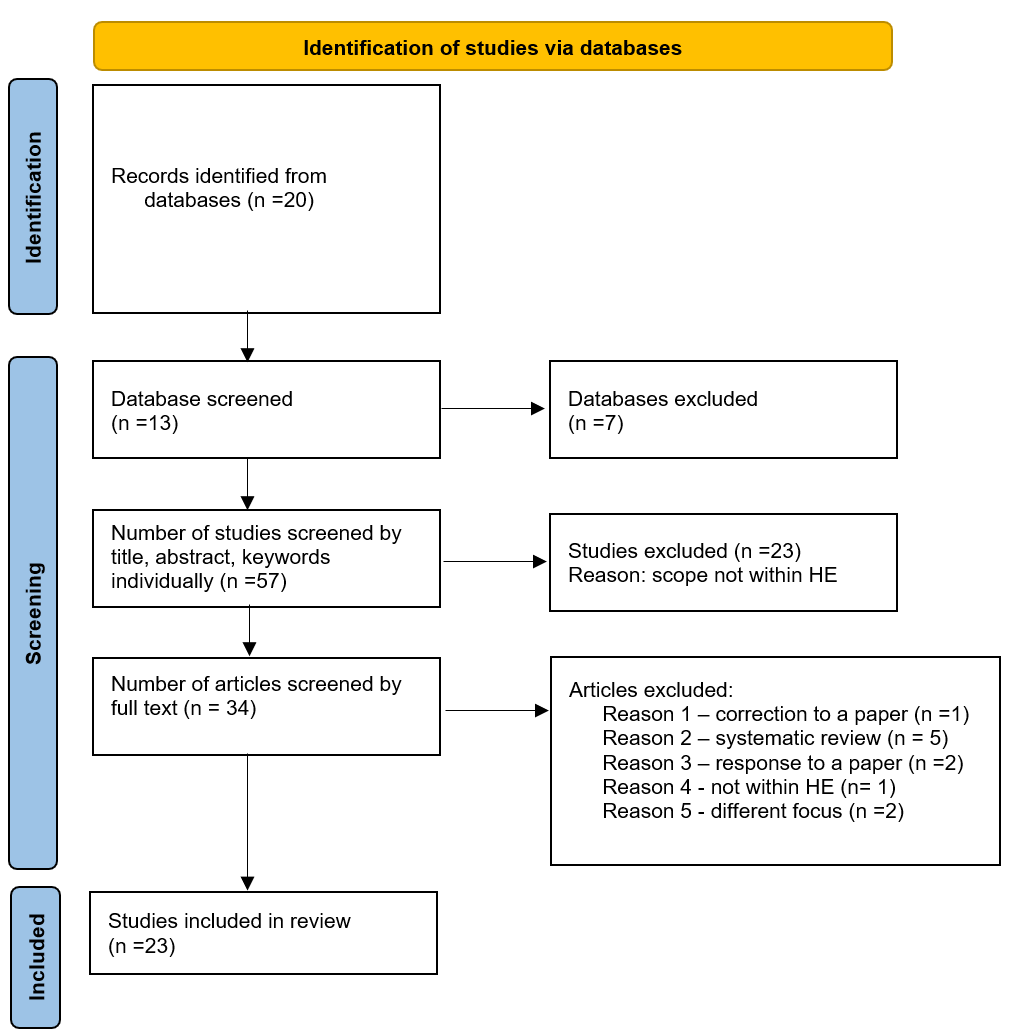

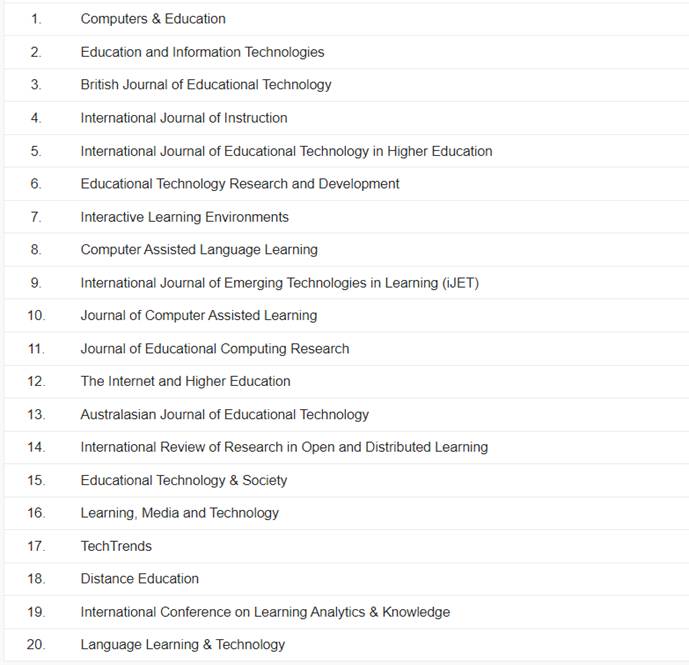

We conducted a systematic review to examine articles that addressed our research questions. We used the PRISMA principles (Liberati et al., 2009) to guide the article selection process, which appears in Figure 3. The use of PRISMA establishes trustworthiness by making our process transparent and allowing others to update or replicate our study (Page et al., 2021). We decided to focus our systematic review on peer-reviewed empirical journal articles. Dissertations and conference proceedings were not considered for this review. To ensure that we were examining high-quality peer-reviewed research, we began by identifying the top 20 educational technology journals according to Google Scholar (Figure 4). This technique of filtering by top journals has been used in other systematic reviews previously (Crompton & Burke, 2018; Moore & Blackmon, 2022). We conducted a search for articles published between 2020 and 2023 in English using the following search strings: ‘emergency remote teaching’ AND ‘higher education, originally screening title, keywords, and abstract in the articles.

We conducted a full-text screening of 34 articles to identify their generic characteristics and to determine if the article met our inclusion criteria (Table 1). The authors assigned an exclusion reason when an article did not meet the criteria. The authors met twice to discuss discrepancies and agreed on inclusion or exclusion.

The included papers were analysed based on two axes: a) general characteristics (year of publication, time period in which the data collection took place, research design, theoretical framework if any, country(ies) involved, target group of participants) and b) the three structures of the SP.

Figure 3. Article selection process

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

|

|

Inclusion |

Exclusion |

|

Literature type |

Empirical research peer reviewed articles |

Systematic reviews; correction or response to a paper |

|

Study focus |

ERT and higher education |

Either not on ERT or not on higher education |

|

Time period |

2020-2023 |

Before 2020 |

|

Language |

English |

Other language |

Figure 4. Journals used for search (source: Google scholar)

After the article selection process was completed, we had to analyse 23 articles. During the full-text review process, we began to identify, for each article, descriptions corresponding to any of the three types of structures comprising SP. The two authors read individually the first five articles of Appendix 1 and had a meeting to compare their notes with respect to how the SP were manifested in the articles. That meeting culminated in a shared understanding concerning how to identify elements of SP in an article. After that meeting, one of the authors analysed the remaining articles (that is, 18 articles) using a spreadsheet taking into account the shared understandings between the authors on how to proceed with the analysis. Therefore, the analysis was guided by the SP framework in this phase and the common understanding between the two analysts. In a second phase, the articles that were focusing on implicit structures (13 articles) were further analysed using the TL framework: disorientating dilemma, transformation, and arriving in some (re)solution(s). Not all 13 articles could be analysed using this perspective, e.g. articles with focus on students or articles that did not focus on teachers’ dilemmas were not selected. Therefore, six articles were analysed deductively using the TL analytical lenses: (a) teacher’s disorientating dilemma(s), (b) transformation, and (c) arriving in some (re)solution. An example of text indicating disorientating dilemmas from (Xie, & Rice, 2021): faculty members becoming more aware of what their challenges are in online teaching and what they need to improve on; followed by an instance indicating transformation: faculty members are looking for people to help them; culminating to some resolution: faculty members are learning that instructional designers are people that can help them with that. Annex 1 presents the analysis of the papers included for initial analysis also denoting papers that were further analysed using TL.

We found that a significant proportion of articles collected their data during the first semester of 2020 and only a few of them took a longitudinal approach data collection stretching to more than a year (Figure 5a). Under the challenging circumstances for both teachers and researchers in higher education, this is not surprising. Almost one out of four articles do not mention the time period in which the data collection take place.

We found that studies are almost equally distributed between qualitative -, quantitative-, and mixed methods research designs (Figure 5b). In geographical terms, the studies took place in their majority in non-European countries (Figure 6). This is interesting because previous systematic reviews are preoccupied with studies that come from European countries.

Figure 5. (a) Study distribution across research design (left) and (b) data collection period (right)

Countries

Figure 6. Study distribution across countries

We found that the studies included in our review are preoccupied with perspectives coming from the main stakeholders, i.e. teachers and/or students (Figure 7a). Perspectives are mostly expressed in the form of stakeholders’ perceptions or views or experiences with ERT in higher education (Figure 6b), rather than observations of teaching or other analytical means.

Figure 7. (a) Study distribution across target group (left) and (b) research focus (right)

Results

Dimensions of SP

As shown in Figure 8, we found many elements discussing the implicit structure, fewer elements on the deep structure, and some elements on the surface structure in the articles included in the review. This is an interesting finding in itself, since typically articles on SP follow the opposite pattern; that is, more elements on the surface structure and few elements on the implicit structure. The remainder of this section describes elements across different SP structures found in the articles.

Figure 8. Frequency of appearance of elements across structure levels of SP

Surface structure: on the positive side, online learning enabled virtual trips and visits (Ng, 2022), interacting remotely with experts and professionals (Ng, 2022; Oliveira et al., 2021), visualisations and simulations (Ng, 2022). On the negative side, it was mostly related to student activities that touch upon operational acts of learning like remembering, comprehending, and analysing (Coşgun Ögeyik, 2022), as well as planning and monitoring (Bailey & Almusharraf, 2022), as opposed to applying, evaluating, and creating (Coşgun Ögeyik, 2022), or reviewing (Bailey & Almusharraf, 2022). On behalf of the teacher, teaching online was mostly related to classroom management or to the administration of learning –like sending reminders, administering assignments, and managing grades (Bolliger & Halupa, 2022). It was easy to present content, give timely feedback on assignments and questions (Weidlich & Kalz, 2021) and to facilitate synchronous and asynchronous interaction and communication (Bolliger & Halupa, 2022) - although it was not easy to facilitate peer feedback or discussions (Weidlich & Kalz, 2021).

Deep structure: The emphasis was on the importance of sustaining the social aspects of education while teaching online: on behalf of the teachers this meant increased interest and difficulty in providing socio-emotional support to the students (Usher et al., 2021) and on behalf of the students, this was translated to lack of social interaction (Yüksel, 2022) leading to feelings of isolation and lack of motivation (Ng, 2022). Also, there is a red thread concerning the positive effect of sustaining a sense of community online (Al Shlowiy et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2022; Ezra et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2022; Milic & Simeunovic, 2022) such as Community of Practice (Oliveira et al., 2021) or Community of Inquiry (Bamoallem & Altarteer, 2022). Methods of student support included widening the teacher-student communication and providing quick student feedback (Bamoallem & Altarteer, 2022; Dorfsman & Horenczyk, 2022; VanLeeuwen et al., 2021). Therefore, there seems to be an assumption that the pedagogical and the social roles should be more interweaved to sustain student engagement, interaction, and motivation. Flexibility was frequently mentioned as an advantage of online or blended education (Baruth et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2022; Dorfsman & Horenczyk, 2022; Kumar et al., 2022).

Implicit structure: There is an emphasis on teachers’ professional role in the remote learning environment covering a range of several distinctively various aspects that can be grouped into three main themes

· managing teachers’ own professional role, accompanied by a sense of pressure (VanLeeuwen et al., 2021) or anxiety (Meishar-Tal & Levenberg, 2021), their perceived inability to manipulate equipment (Ezra et al., 2021; Oliveira et al., 2021), and perceived readiness or capacity for teaching online (Baruth et al., 2021; VanLeeuwen et al., 2021)

· technical problems that contributed to unsuitable online learning environments or pedagogical processes (Baruth et al., 2021; Cahyadi et al., 2022) or diminished learning outcomes (Ezra et al., 2021)

· teacher competence development: teachers’ digital competences (Aranyi et al., 2022) and professional development (Oliveira et al., 2021; Xie & Rice, 2021) for teaching online

· factors positively associated with teachers’ competences: their willingness to conduct online course in the future (Meishar-Tal & Levenberg, 2021), perceived support (Kumar et al., 2022), and their digital pedagogical literacy (Cahyadi, et al., 2022; Dorfsman & Horenczyk, 2022; Kumar et al., 2022), such as their ability to enable interactivity and dialogue online (Kumar et al., 2022).

The first point above is partially associated with the belief that effective online education entails replicating conventional face-to-face education as much as possible. As written in Oliveira et al. (2021):

Since most of the time students had their cameras turned off, teachers could not understand if they fully understood the content being taught. Small details such as facial expressions that express doubts, that were easily perceived in F2F classes, were not observable in this technology-mediated setting. (p. 1367).

On the opposite, measures of ‘pedagogical readiness’ that were suggested in Cahyadi, et al. (2022) argue for a simplified, reduced ‘emergency curriculum’ that caters only for essential student competences.

Furthermore, the ‘hidden curriculum’ of ERT is focusing on the socioemotional aspects while introducing forms of ‘pedagogy of care’. This pinpoints to the importance of trauma-informed and associated practices for university pedagogy and faculty development (VanLeeuwen et al., 2021), care for students and support (Cahyadi, et al., 2022) as well as dealing with power structures (Pischetola et al., 2021) , social inequality (Cahyadi et al., 2022; Ezra et al., 2021; Milic & Simeunovic, 2022), and quality student participation (Pischetola et al., 2021). Inequality was frequently connected to the digital gap (Aranyi et al., 2022). On behalf of the students, it also touches upon the socioemotional dimensions of learning (Dorfsman & Horenczyk, 2022; Milic & Simeunovic, 2022; VanLeeuwen et al., 2021). One study included in our review reveals that the most important concerns for both university students and teachers were related to the emotional dimension of learning (Al Shlowiy et al., 2021).

The student experience was affected by faculty availability/feedback positively (Dorfsman & Horenczyk, 2022; Oliveira et al., 2021) or negatively (Aranyi et al., 2022). Socioemotional aspects of learning were mostly negatively affected (Al Shlowiy et al., 2021; Ezra et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2022; Pischetola et al., 2021): lack of emotional interaction, lack of sense of connectedness/community, feelings of distress (Pischetola et al., 2021; Yüksel, 2022). Finally, with respect to moral dimensions of online learning, committing fraud/cheating in online student assessments was something that concerned teachers (Al Shlowiy et al., 2021; Cahyadi et al., 2022; Oliveira et al., 2021).

Transformative learning process

The articles that gave information about implicit structures mentioned above were further analysed by looking for signs of TL on behalf of the teachers. This section is focusing on the second research question: How was digital transformation touching upon teachers’ professional practices manifested especially in the implicit structures?

The main results of the analysis are:

· Diverse disorienting dilemmas: teachers were faced with diverse dilemmas caused by the abrupt transition to online teaching, which created a sense of unpreparedness, stress, and the need for quick adaptation

· Transformation as a response: in response to these challenges, teachers underwent transformations in their perspectives and practices including recognizing the limitations of their existing competences, confronting the emotional burden of their new responsibilities, and re-evaluating priorities

· Emotional and professional impact: transformative learning processes on behalf of teachers included socioemotional aspects of teaching related to stress, professional competence, personal and professional well-being

· Importance of support and collaboration: underscores the importance of trauma-informed practices, faculty development, and collaboration with support structures/resources such as ICT solutions and instructional designers

· Recognition of student challenges: awareness of the challenges faced by students (such as unstable internet access and other unfavourable situations) and efforts to support students through provision of information and resources whenever possible and practices promoting flexibility and empathy

· Reflection on (emerging) online pedagogies: manifested as making difficult decisions, adopting affective coping strategies, revising student assessment methods; the absence of this critical reflection meant replicating traditional classroom techniques which in turn lead to compromises.

Discussion

University teaching was disrupted during the pandemic. Has this disruption led to new and pedagogically meaningful ways of higher education with respect to the integration of digital technologies in the teaching-learning process? To answer that, we performed a systematic literature review utilising SP as a means to unpack this complex and multifaceted concept. Furthermore, to study digital transformation specifically we employed the theory of TL with a focus on university teachers. We use the term ‘digital metamorphosis’ as a metaphor for the transformation of a caterpillar into a butterfly to denote a multi-stage process that culminates into something new. The caterpillar stage represents the initial state - in this context, traditional teaching practices being effective in a physical classroom setting. The cocoon stage signifies the transitional phase in which the caterpillar must form a cocoon to initiate its metamorphosis - a period of trial, error, and learning. The final transformation into a butterfly symbolises how the butterfly finds itself equipped with new capabilities, behaviours, and habits that enable it to interact with its ecosystem in new ways.

Concerning the first research question (“What were the surface -, deep -, and implicit structures?”), the most interesting finding stems from the implicit structures delving into the ‘why’ and assumed norms that emerged: teachers managing their professional role, technical challenges making their work difficult, the need for competence development, and factors positively associated with it. Notwithstanding are the social and affective aspects of teaching and learning: encapsulating a pedagogy of care related to trauma-informed practices and care for students; dealing with power structures, social inequality, and student participation; emotional well-being of students and teachers; and moral/ethical dimensions, such as cheating in the exams. These findings are not only significant for the first research question, but they are also addressing a broader gap in the relevant literature regarding implicit structures in online learning environments. Therefore, these findings are valuable not only for the specific context of this study, but also for the online learning research field, in general. This shift towards a focus on the hidden curriculum and TL on behalf of the university teachers can be interpreted in the light of the words of Bayne (2015) about the increased (and maybe underrated before the pandemic) value that lies in exploring our values and beliefs as teachers and if or how learning technologies fail to realise our expectations. This shift is the first constituent element of the digital metamorphosis.

The importance of social learning also emerges at the level of deep structures, along with the flexibility aspect linked to teaching and learning online. Sustaining social learning presented challenges for teachers, while flexibility was easily enabled for both teachers and students in the online setting. This aligns with studies reporting that the pandemic led to opportunities promoting student learning through enhanced flexibility (Adedoyin & Soykan, 2023).

At the surface level of SP the pedagogical added value of using technology appears to be a central issue. Where can this value come from? The interpretation of our findings suggest that it can come from teaching-learning activities which are difficult to be implemented without the use of these learning technologies. This pinpoints to specific paradigms, such as to the use technology to enable something new (e.g. new content representations enabled by virtual trips and visits) or supporting teachers in facilitating social learning. Social learning and teachers’ competence emerge as two important themes crossing the three SP structures one way or another. In conclusion, effectively teaching online entails embedding resilience and empathy in models of faculty preparedness coupled with a focus on digital pedagogical competence and professional judgement in relation to the use of learning technologies. This re-conceptualisation of faculty competence is the second constituent element of a digital metamorphosis that enables new paradigms of education.

Regarding the second research question (“How was digital transformation manifested?”), digital transformation herein refers to teachers’ viewpoint. It was manifested through interrelated facets: diverse disorienting dilemmas, transformation as a response, emotional and professional impact, importance of support and collaboration, recognition of student challenges and reflection on (emerging) online pedagogies. This re-conceptualisation of digital transformation is the third constituent element of a digital metamorphosis.

Regarding the third research question (“What are the ensuing implications for the digital transformation in higher education?”), the article proposes a theoretical and methodological approach to studying digital transformation in higher education. The theoretical framework proposed herein operates in the intersection of higher education and adult learning, while the proposed methodology outlines steps for employing this framework to study digital transformation:

· Identify SP across the three types of structures: what, how, and why

· Identify signs of TL on behalf of the teachers, especially in the implicit structures

· Analyse each of the implicit structures of point 2 in terms of

o teachers’ disorientating dilemmas

o transformation as a response to those dilemmas

o resolution(s)[2]

· Conclude on how digital transformation was manifested as well as on its effects

This theoretical contribution goes beyond the context of the pandemic addressing the under-theorisation surrounding university teachers and TL facilitated by digital technologies. It provides a clear and specific framework for conceptualising digital metamorphosis shedding light on the epistemology and the didactics of teaching online in higher education which is fundamental in understanding educational processes that depend on the digital competences of teachers (Bartolomé et al., 2018; Castañeda & Selwyn, 2018). Its practical contribution lies in its applicability for faculty developers or instructional designers to support prospective teachers’ critical reflection for (digital) transformation in higher education i.e. what we coin as digital metamorphosis in university pedagogy herein. This, in turn, introduces a new professional development model for technology integration. Higher Education Institutions can leverage this framework to provide professional development opportunities. In a broader perspective, this research work aligns with the social mandate to build more resilient higher education institutions for the future with competent teachers. The authors of this article invite researchers and practitioners to further employ and test this framework in their own contexts to draw conclusions about its suitability and usefulness.

In this context, it is also important to acknowledge student agency since teachers cannot undergo change without corresponding shifts among students. Therefore, research on the identification of the competencies that both teachers and students must acquire during the continuing shift into a ‘new normal’ for post pandemic educational practices could inform the digital transformation of higher education (Otto et al, 2024).

Limitations for this work involve the relatively small number of articles that were included in the review, as well as the selection criteria suggesting only articles from 20 journals with the highest h-index in the field of educational technology. Therefore, recommendations for future research involve a literature review with broader selection criteria that would secure a larger pool of articles to be included in the analysis.

Declarations

Availability of data and material

The articles included in review are listed in Annex 1. The analysis if the articles that were analysed using the TL framework can also be provided upon request to the authors.

Funding

This work is partially funded by the Internal research support at the Department of Education (IPED) of the University of Oslo (UiO).

References

Adedoyin, O. B., & Soykan, E. (2023). Covid-19 pandemic and online learning: The challenges and opportunities. Interactive learning environments, 31(2), 863-875. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1813180

Advance HE (2023). Professional Standards Framework for teaching and supporting learning in higher education 2023. Advance HE. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/professional-standards-framework-teaching-and-supporting-learning-higher-education-0

Al Issa, H. A., Kairouz, H., & Yuksel, D. (2022). EFL Teachers' challenges and coping strategies in emergency remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. In El-Henawy, W. M., & del Mar Suárez, M. (Eds.), English as a foreign language in a new-found post-pandemic world (pp. 93-116). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-6684-4205-0.ch005

Alsaywid, B. S., Alajlan, S. A., & Lytras, M. D. (2023). Transformative learning as a bold strategy for the Vision 2030 in Saudi Arabia: Moving higher healthcare education forward. In Vaz de Almeida, C., & Lytras, M. D. (Eds.), Technology-enhanced healthcare education: Transformative learning for patient-centric health (pp. 187-207). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-83753-598-920231014

Al Shlowiy, A., Al‐Hoorie, A. H., & Alharbi, M. (2021). Discrepancy between language learners and teachers concerns about emergency remote teaching. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 37(6), 1528-1538. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12543

Aranyi, G., Tóth, Á. N., & Veisz, H. (2022). Transitioning to emergency online university education: An analysis of key factors. International Journal of Instruction, 15(2), 917-936. https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2022.15250a

Bali, M., & Caines, A. (2018). A call for promoting ownership, equity, and agency in faculty development via connected learning. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 15(46). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-018-0128-8

Bailey, D. R., & Almusharraf, N. (2022). A structural equation model of second language writing strategies and their influence on anxiety, proficiency, and perceived benefits with online writing. Education and information technologies, 27(8), 10497-10516. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11045-0

Bamoallem, B., & Altarteer, S. (2022). Remote emergency learning during COVID-19 and its impact on university students' perception of blended learning in KSA. Education and Information Technologies, 27(1), 157-179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10660-7

Bartolomé, A., Castañeda, L., & Adell, J. (2018). Personalisation in educational technology: The absence of underlying pedagogies. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 15, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-018-0095-0

Baruth, O., Gabbay, H., Cohen, A., Bronshtein, A., & Ezra, O. (2021). Distance learning perceptions during the coronavirus outbreak: Freshmen versus more advanced students. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 37(6), 1666-1681. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12612

Bayne, S. (2015). What's the matter with ‘technology-enhanced learning’?. Learning, media and technology, 40(1), 5-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2014.915851

Biesta, G. (2007). Why “what works” won’t work: Evidence‐based practice and the democratic deficit in educational research. Educational Theory, 57(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-5446.2006.00241.x

Bolliger, D. U., & Halupa, C. (2022). An investigation of instructors’ online teaching readiness. TechTrends, 66(2), 185-195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-021-00654-0

Bond, M., Bedenlier, S., Marín, V. I., & Händel, M. (2021). Emergency remote teaching in higher education: Mapping the first global online semester. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 18(50). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-021-00282-x

Brookfield, S. (1995). Adult learning: An overview. International Encyclopedia of Education, 10(3), 375-380.

Cahyadi, A., Hendryadi, Widyastuti, S., & Suryani. (2022). COVID-19, emergency remote teaching evaluation: The case of Indonesia. Education and Information Technologies, 27(2), 2165-2179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10680-3

Castañeda, L., & Selwyn, N. (2018). More than tools? Making sense of the ongoing digitizations of higher education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 15(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-018-0109-y

Chen, V., Sandford, A., LaGrone, M., Charbonneau, K., Kong, J., & Ragavaloo, S. (2022). An exploration of instructors' and students' perspectives on remote delivery of courses during the COVID‐19 pandemic. British Journal of Educational Technology, 53(3), 512-533. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13205

Coşgun Ögeyik, M. (2022). Using Bloom’s digital taxonomy as a framework to evaluate webcast learning experience in the context of Covid-19 pandemic. Education and Information Technologies, 27(8), 11219-11235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11064-x

Crompton, H., & Burke, D. (2018). The use of mobile learning in higher education: A systematic review. Computers & Education, 123, 53-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.04.007

Cutri, R. M., & Mena, J. (2020). A critical reconceptualization of faculty readiness for online teaching. Distance Education, 41(3), 361-380. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2020.1763167

Dorfsman, M., & Horenczyk, G. (2022). The coping of academic staff with an extreme situation: The transition from conventional teaching to online teaching. Education and Information Technologies, 27, 267-289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10675-0

Dow, A., Pfeifle, A., Blue, A., Jensen, G. M., & Lamb, G. (2021). Do we need a signature pedagogy for interprofessional education?. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 35(5), 649-653. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2021.1918071

Eaton, S. E., Brown, B., Schroeder, M., Lock, J., & Jacobsen, M. (2017). Signature pedagogies for e-learning in higher education and beyond. University of Calgary. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/51848

Ezra, O., Cohen, A., Bronshtein, A., Gabbay, H., & Baruth, O. (2021). Equity factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: Difficulties in emergency remote teaching (ERT) through online learning. Education and Information Technologies, 26(6), 7657-7681. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10632-x

Falk, B. (2006). A conversation with Lee Shulman—signature pedagogies for teacher education: Defining our practices and rethinking our preparation. The New Educator, 2(1), 73-82. https://doi.org/10.1080/15476880500486145

Friedman, Z. (2023). Signature pedagogies versus trauma informed approaches: Thematic analysis of graduate students’ reflections. Pedagogy in Health Promotion, 9(1), 17-26. https://doi.org/10.1177/23733799221118575

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (1999). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(00)00016-6

Guppy, N., Verpoorten, D., Boud, D., Lin, L., Tai, J., & Bartolic, S. (2022). The post‐COVID‐19 future of digital learning in higher education: Views from educators, students, and other professionals in six countries. British Journal of Educational Technology, 53(6), 1750-1765. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13212

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., & Bond, A. (2020). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. EDUCAUSE Review, 27(1), 1-9.

Kelly, T. (2022). Signature pedagogies--A cautionary tale. Imagining SoTL, 2(1), 10-18. https://doi.org/10.29173/isotl599

Kitchenham, A. (2006). Teachers and technology: A transformative journey. Journal of Transformative Education, 4(3), 202-225. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344606290947

Kitchenham, A. (2008). The evolution of John Mezirow's transformative learning theory. Journal of Transformative Education, 6(2), 104-123. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344608322678

Kumar, J. A., Richard, R. J., Osman, S., & Lowrence, K. (2022). Micro-credentials in leveraging emergency remote teaching: the relationship between novice users’ insights and identity in Malaysia. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 19, 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-022-00323-z

Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P., Clarke, M., Devereax, P. J., Kleijnen, J., & Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151(4), W-65. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136

Maclaren, P. (2014). The new chalkboard: the role of digital pen technologies in tertiary mathematics teaching. Teaching Mathematics and Its Applications: International Journal of the IMA, 33(1), 16-26. https://doi.org/10.1093/teamat/hru001

Meishar-Tal, H., & Levenberg, A. (2021). In times of trouble: Higher education lecturers' emotional reaction to online instruction during COVID-19 outbreak. Education and Information Technologies, 26(6), 7145-7161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10569-1

Mezirow, J. (1978). Perspective transformation. Adult Education, 28(2), 100-110. https://doi.org/10.1177/074171367802800202

Mezirow, J., & Taylor, E. W. (2009). Transformative learning theory. Transformative learning in practice: Insights from community, workplace, and higher education (pp. 18-31). Jossey-Bass.

Milic, S., & Simeunovic, V. (2022). Teachers’ roles in online learning communities: A case study from the digitally underdeveloped country. Interactive Learning Environments, 32(1), 144-155. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2022.2081210

Mishra, S., Sahoo, S., & Pandey, S. (2021). Research trends in online distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Distance Education, 42(4), 494-519. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2021.1986373

Moore, R. L., & Blackmon, S. J. (2022). From the learner's perspective: A systematic review of MOOC learner experiences (2008–2021). Computers & Education, 104596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2022.104596

Ng, D. T. K. (2022). Online aviation learning experience during the COVID‐19 pandemic in Hong Kong and Mainland China. British Journal of Educational Technology, 53(3), 443-474. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13185

Nguyen, Q., Rienties, B., Toetenel, L., Ferguson, R., & Whitelock, D. (2017). Examining the designs of computer-based assessment and its impact on student engagement, satisfaction, and pass rates. Computers in Human Behavior, 76, 703-714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.028

Oliveira, G., Grenha Teixeira, J., Torres, A., & Morais, C. (2021). An exploratory study on the emergency remote education experience of higher education students and teachers during the COVID‐19 pandemic. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(4), 1357-1376. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13112

Olson, K., & Clark, C. M. (2009). A signature pedagogy in doctoral education: The leader–scholar community. Educational Researcher, 38(3), 216-221. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X09334207

Otto, S., Bertel, L. B., Lyngdorf, N. E. R., Markman, A. O., Andersen, T., & Ryberg, T. (2024). Emerging digital practices supporting student-centered learning environments in higher education: A review of literature and lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. Education and Information Technologies, 29(2), 1673-1696. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-11789-3

Öztok, M. (2019). The hidden curriculum of online learning: Understanding social justice through critical pedagogy. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429284052

Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L. A., Stewart, L. A., Thomas, J., Tricco, A. C., Welch, V. A., Whiting, P., & McKenzie, J. E. (2021). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. British Medical Journal, 372:n160. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n160

Parker, M., Patton, K., & O'Sullivan, M. (2016). Signature pedagogies in support of teachers’ professional learning. Irish Educational Studies, 35(2), 137-153. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2016.1141700

Pischetola, M., de Miranda, L. V. T., & Albuquerque, P. (2021). The invisible made visible through technologies’ agency: A sociomaterial inquiry on emergency remote teaching in higher education. Learning, Media and Technology, 46(4), 390-403. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2021.1936547

Quinlan, K. M., Buelens, H., Clement, M., Horn, J., & Rump, C. Ø. (2017). Educational enhancement in the disciplines: Models, lessons and challenges from three research-intensive universities. In Stensaker, B., Bilbow, G. T., Breslow, L., & Van der Vaart, R. (Eds.), Strengthening teaching and learning in research universities: Strategies and initiatives for institutional change (pp. 43-71). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56499-9_3

Reinhardt, K. S., Robertson, P. M., & Johnson, R. D. (2021). Connecting inquiry and Universal Design for Learning (UDL) to teacher candidates’ emerging practice: Development of a signature pedagogy. Educational Action Research, 31(3), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2021.1978303

Rozo, H., & Ramírez-Montoya, M. S. (2025). Teaching and learning strategies in remote education: A systematic review of the literature. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 41(2), 71–88. https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.10070

Salmon, G. (2014). Learning innovation: A framework for transformation. European Journal of Open, Distance and E-Learning (EURODL), 17(2), 220-236. https://doi.org/10.2478/eurodl-2014-0031

Scherer, R., Howard, S. K., Tondeur, J., & Siddiq, F. (2021). Profiling teachers’ readiness for online teaching and learning in higher education: Who’s ready? Computers in Human Behavior, 118, 106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106675

Shulman, L. S. (2005). Signature pedagogies in the professions. Daedalus, 134(3), 52-59.

Tarling, I., & Ng’ambi, D. (2016). Teachers pedagogical change framework: A diagnostic tool for changing teachers’ uses of emerging technologies. British Journal of Educational Technology, 47(3), 554–572. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12454

Taylor, E. W., & Cranton, P. (2012). The handbook of transformative learning: Theory, research, and practice. John Wiley & Sons.

UNESCO (2021). COVID-19: Reopening and reimagining universities, survey on higher education through the UNESCO National Commissions. United Nations COVID-19 Education Response. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000378174.locale=en

Usher, M., Hershkovitz, A., & Forkosh‐Baruch, A. (2021). From data to actions: Instructors' decision making based on learners' data in online emergency remote teaching. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(4), 1338-1356. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13108

VanLeeuwen, C. A., Veletsianos, G., Johnson, N., & Belikov, O. (2021). Never‐ending repetitiveness, sadness, loss, and “juggling with a blindfold on:” Lived experiences of Canadian college and university faculty members during the COVID‐19 pandemic. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(4), 1306-1322. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13065

Watermeyer, R., Crick, T., Knight, C., & Goodall, J. (2021). COVID-19 and digital disruption in UK universities: Afflictions and affordances of emergency online migration. Higher Education, 81, 623-641. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00561-y

Weidlich, J., & Kalz, M. (2021). Exploring predictors of instructional resilience during emergency remote teaching in higher education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 18, 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-021-00278-7

Xie, J., & Rice, M. F. (2021). Instructional designers’ roles in emergency remote teaching during COVID-19. Distance Education, 42(1), 70-87. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2020.1869526

Xu, Y., Jin, L., Deifell, E., & Angus, K. (2021). Chinese character instruction online: A technology acceptance perspective in emergency remote teaching. System, 100, 102542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2021.102542

Yüksel, H. G. (2022). Remote learning during COVID-19: cognitive appraisals and perceptions of English medium of instruction (EMI) students. Education and Information Technologies, 27(1), 347-363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10678-x

Appendix 1: Basic information about the studies included in the review

|

Authors and year |

Research design |

Country |

Time period |

Theoretical framework |

|

|

|

Usher et al. (2021) |

Quantitative |

Middle East, North America, Europe, Asia, Africa and South America |

March–June 2020 |

Not mentioned |

|

|

Chen et al. (2022) |

Mixed |

Canada |

Summer 2020 - Winter 2021 |

Not mentioned |

|

|

Ng (2022) |

Mixed |

China |

Not mentioned |

Four motivational constructs |

|

Yes |

VanLeeuwen et al. (2021) |

Qualitative |

Canada |

June- July 2020 |

Not mentioned |

|

Yes |

Oliveira et al. (2021) |

Qualitative |

Portugal |

April-June 2020 |

Technology Mediated Learning |

|

|

Guppy et al. (2022) |

Mixed |

Philippines, Australia, Netherlands, Canada, Belgium, USA |

May and August 2020 |

Not mentioned |

|

|

Coşgun Ögeyik (2022) |

Mixed |

Turkey |

Spring 2020 |

Bloom's digital taxonomy |

|

|

Bailey & Almusharraf (2022) |

Quantitative |

South Korea |

Not mentioned |

Not mentioned |

|

|

Yüksel (2022) |

Quantitative |

Turkey |

Not mentioned |

Cognitive appraisal |

|

|

Dorfsman & Horenczyk (2022), |

Mixed |

Israel |

Not mentioned |

Not mentioned |

|

|

Bamoallem & Altarteer (2022) |

Quantitative |

Saudi Arabia |

May-June 2020 |

Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology

(UTAUT), |

|

Yes |

Meishar-Tal & Levenberg (2021) |

Quantitative |

Israel |

1st semester of 2020 |

Not mentioned |

|

Yes |

Cahyadi et al. (2022) |

Mixed |

Indonesia |

July 2020-January 2021 |

Context, Input, Process, and Product (CIPP) model |

|

|

Ezra et al. (2021) |

Qualitative |

Israel |

Mar-20 |

Three constructs on equity |

|

|

Kumar et al. (2022) |

Qualitative |

Malaysia |

Not mentioned |

Digital learning identity (DLI) & |

|

|

Weidlich & Kalz (2021) |

Quantitative |

27 countries |

November 2020- January 2021 |

Instructional resilience |

|

|

Aranyi et al. (2022) |

Quantitative |

Hungary |

December 2020-January 2021 |

Person-Artefact-Task model (PAT) |

|

|

Milic & Simeunovic (2022) |

Qualitative |

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

Not mentioned |

Not mentioned |

|

|

Baruth et al. (2021) |

Mixed |

Israel |

2nd semester of 2020 |

Own framework: Distance Learning Success Dimensions (DLSD) |

|

|

Al Shlowiy et al. (2021) |

Mixed |

Saudi Arabia |

1st semester of 2020 |

Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) |

|

Yes |

Pischetola et al. (2021) |

Qualitative |

Brazil |

1st semester of 2020 |

Own sociomaterial theoretical framework |

|

|

Bolliger & Halupa (2022) |

Quantitative |

USA |

May-June 2020 |

Faculty Readiness to Teach Online (FRTO) instrument |

|

Yes |

Xie & Rice (2021) |

Qualitative |

USA |

June-July 2020 |

Not mentioned |

Abbreviations

ERT Emergency Remote Teaching

SP Signature Pedagogies

TL Transformative Learning