Navigating creativity, technology, and human-centred learning:

An open, collaborative education community reflection

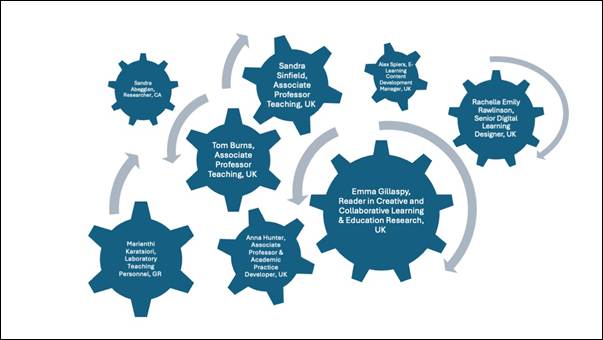

Sandra Abegglen1, Tom Burns2, Sandra Sinfield2, Emma Gillaspy3, Rachelle Emily Rawlinson4, Alex Spiers5, Marianthi Karatsiori6 and Anna Hunter7

1 University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada

2 London Metropolitan University, London, UK

3 University of Central Lancashire, Preston, UK

4 Durham University, Durham, UK

5 Kings College London, London, UK

6 University of Macedonia, Thessaloniki, Greece

7 University of Law, UK

Abstract

We live in a postdigital world - a messy and paradoxical condition of art and media after a series of digital technology revolutions (Anderson et al., 2014, cited in Jandrić et al., 2018). ‘Postdigital’ does not mean that we have moved beyond the influence of technology, but rather we exist in a digitally saturated landscape where it no longer makes sense to distinguish, say, between education and so-called Technology Enhanced Education. Technology is a fact of our educational lives. This paper examines the postdigital classroom as a dynamic space where technology is not merely adopted for its own sake but thoughtfully integrated to foster equitable, student-centred learning. Through provocative vignettes, the authors critically explore the interplay between digital tools and hands-on, embodied practices such as making, drawing, and play. They advocate for a reimagined postdigital classroom - one that is flexible, inclusive, and co-created by educators, technologists - and students. By striking a balance between technological innovation and human creativity, this vision moves beyond passive digital transformation toward a future where education is imaginative, adaptive, and deeply humane.

Keywords

postdigital classroom, equitable teaching and learning, inclusive pedagogy, creativity, pirates

Introduction

We live in a messy and paradoxical condition of art and media after a series of digital technology revolutions (Anderson et al. 2014, cited in Jandrić et al., 2018; Fawns, 2018). ‘Postdigital’ does not mean that we have moved beyond the influence of technology, rather we exist in a technology-infused eco-system. Technology is a fact of our educational lives; however, this does not mean that technology as technology must exist as an unexamined part of our practice. Together we, the #creativeHE crew, wanted to explore this contested territory, inviting fellow travellers, academics, teachers, and technologists in Higher Education (HE) particularly, to come on board so that together we can map an optimistic and positive journey.

For Pepperell and Punt (2000, p. 2),

the term Postdigital is intended to acknowledge the current state of technology while rejecting the conceptual shift implied in the ‘digital revolution’ - a shift apparently as abrupt as the ‘on/off’ ‘zero/one’ logic of the machines now pervading our daily lives.

In the evolving postdigital landscape, Sir Ken Robinson’s (2016) asserts that “creativity is important in education”. This prompts a critical question: What does this mean for the future of the postdigital classroom where there is a strong focus on technology and Technology Enhanced Teaching and Learning? As we navigate the complex waters of modern HE, where Technology Enhanced Learning and Artificial Intelligence (AI) are seen as the panacea for both academic success and professional despair, it becomes clear that the journey ahead, though uncertain, must be anchored in humane creativity where the collective fuels both the process and the outcomes of our endeavour.

This collaborative paper is based on provocative vignettes produced by members of #creativeHE (viz. https://creativehecommunity.wordpress.com/), a loose affiliation of academics in further and higher education committed to seeding creative and ludic practices as part of active, holistic and reparative pedagogy. Together we explore the concept of the postdigital classroom as a hybrid space, encompassing both physical and online learning environments - and ones that are physical and online at the same time - where the integration of technology and human-centred pedagogy is arguably something to be explored and problematised if it is to be harnessed for liberatory purpose (Freire, 2000). We collectively argue for a reimagining of the postdigital classroom, where ‘appropriate’ technologies in all their diversity and affordances are leveraged in support of inclusive, creative, student-centred learning, rather than adopting ‘technology for technology’s sake’ (Lederman & Niess, 2000). The postdigital classroom must strike a balance between technologically driven solutions and hands-on approaches like making, drawing, and playing, activities often overshadowed by the allure of expensive technological tools and software applications.

We propose that whilst technology in the postdigital classroom can be used in ways that are imaginative, collaborative, and aligned with the goal of creating more equitable and inclusive learning environments, the classroom of the future should not only focus on digital transformation but also on the humans within it. The postdigital classroom needs to be a space where collaboration between educators, students, pedagogues, and technology specialists (where they are separated from other academic colleagues) create learning experiences that are inclusive, engaging, and reflective of the complexities of our postdigital age. In short, the postdigital classroom of the future should be a space that acknowledges us as thinkers and makers, feelers, and doers; places jointly and inclusively created and owned by all stakeholders including educators and students, pedagogues, and technologists alike. It should harness all of our very human attributes, whilst being flexible, responsive and adaptable to the needs of all learners. It is only by building on all that the humans can do in practice, that we can recognise that while we cannot predict the future (Barnett, 2007), we can build our capacities and resilience to shape it ‘well.’

Disrupted pedagogy

The abrupt pivot to online learning in 2020, driven by the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighted a fundamental disconnect in education. While it compelled educators to experiment with new technologies and pedagogical approaches, the chance for a collective reflection on what worked, what did not, and what should be developed further was largely missed (Abegglen et al., 2022). Technology, in and of itself, continued to be valorised, but whilst explored in practice by those teaching and facilitating learning during the pandemic, arguably it was not seen by traditional managerial leadership as part of a new and potentially liberatory pedagogy in a de facto postdigital world (Abegglen et al., 2022). Rather, if they addressed it at all, it was in terms of how to use the technology not just to surveille staff and students, but to better micromanage their time in and out of the classroom. Arguably, this approach continues to stifle innovative uses of pedagogy, assessment, and technology, including AI; in practice cultivating a hostile environment for exploration and discovery, making creativity and innovation transgressive (viz. Noble, 2003). This raises a crucial question: What does a postdigital classroom require to truly cultivate creativity, equity, inclusivity and humanity?

As progressive postdigital practitioners, such as members of #creativeHE, strive to decolonise educational practices and enhance the creativity and inclusivity of postdigital classrooms, revisiting the concept of “appropriate technology” (Schumacher, 2011) - and ‘small is beautiful’ - could provide a pathway for re-theorising practice, and opening our minds to all that can take place in a classroom with and without technology as technology. Such an approach would acknowledge the much needed balance between technology and pedagogy, considering what truly enriches the learning environment and makes it ‘more humane.’ However, when decisions about educational technology are made by those removed from the classroom, and often far removed from the theory and practice of pedagogy, andragogy and heutagogy (Blasche & Hase, 2016; Gillaspy & Vasilica 2021), a disjointed approach emerges. This gap can suffocate creativity, reducing education to a mechanistic exercise rather than a dynamic and transformative process.

To bridge this divide, we argue, it is imperative to shift decision-making closer to those who teach and learn, grounding technological integration in thoughtful pedagogy and a commitment to inclusivity in thinking, feeling, and doing. Only then can the postdigital classroom reach its full potential as a space for human, humane, equitable and imaginative learning.

Method: Vignettes

As a fluid collective of academics committed to creative practices, we wanted to explore this conflicted educational terrain: What are the benefits and potential harms of technology when integrated so apparently seamlessly into the practices of our institutions and of HE per se? As befits our approach to practice overall, we wanted to embrace a creative method (Kara, 2020) that would allow us freedom and agency within the process. Vignettes provide a method that makes space for voice and personal storytelling. Woven together they potentially work to create meanings that are greater than the sum of the parts. Our approach has been very much to let each author write their piece their way: with references or without, or with sparse and very personal referencing. This is quasi-academic writing that we wanted completely owned by each author. Vignettes are concise, descriptive accounts or narratives that illustrate specific experiences, events, or perspectives, somewhat akin to collaborative autoethnography (viz. Gillaspy et al., 2022; Lapadat, 2017).

As authors we collected data using the vignettes that we ourselves produced as part of, and as triggers for, reflection, exploration, and dialogue to gain insights into the postdigital classroom. Vignette research has gained international recognition, sparking interest from a wide range of individuals and institutions in global contexts (see, for example Agostini et al., 2024). For us, they provide a way to capture the richness and diversity of our individual voices and contextual nuances, making them especially suited to this collaborative, co-authored paper where we, as globally dispersed educators, come together, to jointly reflect on the postdigital classroom and new and old technologies as we personally experience them. In practice, we are braiding together the methods of collaborative autoethnography (Gillaspy et al., 2022; Lapadat, 2017), the case study (Stake, 1995) and bricolage (Wheeler, 2018) to gain creative insights into the various ways our postdigital realities are experienced across a range of institutions and pedagogic spaces.

In the process, we the authors, became a group of researchers individually and collectively drawing on our memories, thoughts, experiences, and intellectual enquiries such that the collected vignettes became/become “an embodied sense of what happened [and is happening]” (Davies & Gannon, 2006, p. 3). This enabled a rich uncovering of experiences and approaches within ‘real’ settings (Cousin, 2009; Punch, 2014) sparking deeper reflection and discussion. Overall, this created an intrinsic case study (Stake, 1995), where the authors taking part are involved in the processes under investigation, creating a joint palimpsest of experiences and expertise. This represents an ethical procedure as all the authors are voluntary participants, as both contributors to and recipients of the research. As this is a form of ‘insider research’, we are conscious of our positionality: we are not neutral with respect to our data generation. Rather, we bring knowledge and familiarity to the inquiry that is made transparent yet kept subjective (Greene, 2014). We do not suggest that there is (one) objective truth in our vignettes, rather we wanted to capture strong visceral, emotional or intellectual reactions that are personal and open to further enquiry and analysis.

In the following, we weave together our vignettes to create a joined yet multifaceted ‘argument’ that reflects the collective insights of the group. To do so, we use the metaphor of “the (pirate) ship” (Coniff Allende, 2018) - with the vignettes charting the collective voyage like snapshots from the deck, with each crew member offering a unique outlook. The vignettes constitute the individual voice as well as the spirit of collaborative co-authorship (Abegglen et al., 2022; Burns et al., 2023; Jandrić et al., 2023), with every contribution shaping the broader narrative, much like the combined efforts of a ship’s crew navigating the open seas.

Figure 1. Our #creativeHE collective with roles. Image created by Sandra Abegglen CC BY 4.0 DEED.

Postdigital Vignettes

In the following, we present the personal vignettes that (A) outline how we, as individual educators, navigate the postdigital classroom utilising creativity and creative pedagogies, and (B) provide a critical yet hopeful vision for a more creative and inclusive HE. The vignettes are presented in the random order written in a joined online document so readers can navigate them not as a narrative building to a climax, but as anchor points on a map charting their own journey through the choppy waters of our postdigital reality.

‘Fail we may. Sail we must’: Alex Spiers, King’s College London

Andrew Weatherall (DJ & Musician) was struck by the sentiment of the phrase, “Fail we may. Sail we must”, so much so, he had it tattooed on his arms. Since his death in 2020, the phrase resonated with many, becoming associated with perseverance and pushing forward despite setbacks. This could be the motto for those working as advocates for the positive use of digital technology and social media in UK HE. Postdigital waters constitute a rough sea to navigate right now.

When I think back to the time I joined Twitter (now X) in 2009, it still felt like I had tapped into an endless sea of ideas, comments and connections. It was an evolving digital common where I, like many in my field, engaged in discourse. It was a dynamic and open space for sharing ideas, fostering collaborations, and building professional networks. As an open educational practitioner (viz. Weller, 2011), my work centred on producing and sharing open educational artefacts or resources (OERs) through Creative Commons licensing and blogging platforms, primarily microblogging on Twitter. This approach aligned with my values of lowering barriers to access learning, ensuring education remained open, transparent, and reachable beyond university walls.

I followed researchers, education developers, journalists, and technologists and this provided me with a steady stream of news, activity, and commentary from across the world. My world expanded. I found mentors and friends, discovered articles, thought pieces, books and theories, and I am sure that working in this open space, in an open way, has helped me gain and maintain employment over the years. Twitter was not just a platform; it was a connecting undercurrent bringing together all my interests and workplace focus into one space.

Over the years, my participation in open, cross-institutional events and communities of practice deeply influenced my teaching and learning. Twitter was integral to this evolution, providing an open and supportive environment where HE professionals could congregate, exchange knowledge, and explore collaboration (Cronin, 2017). Carrigan (2016) describes social media as a ‘global academic department’, facilitating corridor-style conversations beyond institutional boundaries. Hashtags became a way to find fellow travellers: those such as #BYOD4L (Bring Your Own Devices for Learning), #ScoMedHe (Social Media in Higher Education), #creativeHE (Creative Higher Education), and #LTHEchat (Learning and Teaching in Higher Education chat) became the regular stream for engagement, influencing my practice, professional relationships, and leadership opportunities.

Then, in October 2022, Elon Musk happened. Taking control of the platform and paying 44 billion for the privilege. However, it is important to remember that Twitter already faced significant challenges before this. Its financial viability was questionable, exacerbated by a surge in spam and bot accounts, a lack of innovation, and increasing competition (Conger & Mac, 2024).

The once vibrant digital landscape I spent so much time in, had become a tempestuous sea of misinformation. You could not hear the trustworthy voices anymore because they were drowned out by ever growing waves of conspiracy theories and fake anger.

Frustrating as this was, I still hoped my use of it would help me navigate this noise and still extract benefits from being here. I tried to carefully choose who I followed and block anything I did not want to see, thinking I could create a small version of the old, good community. But it did not work. It was a bit like trying to breathe underwater. The platform’s algorithm kept pushing things that I did not want to engage with, making thoughtful conversations evaporate over time. As such, those people who made the platform interesting and smart slowly left. The noise of Twitter that was useful and positive, over time became silent.

I explored alternatives - Bluesky, Mastodon, Threads - each offering aspects of what had been lost but none fully replicating the ecosystem of ideas, support, and collaboration that Twitter had once fostered. The strength of the platform had never been its mechanics alone but the people who inhabited it, and now, those people were scattered across diverse digital spaces, with some leaving altogether.

At this point in 2025, Bluesky offers the most hope for those who have been set adrift on the social media seas, searching for kindred spirits and old friends, acquaintances, or familiar voices. This is due to the platform having many similarities with Twitter, such as being able to follow hashtags, find and follow other users and engage in posts via replies and likes. However, as Tattersall (2024) reminds us, the “decline of X is an opportunity to do social media differently - but combining ‘safe’ and ‘profitable’ will still be a challenge”.

Thinking positively about Bluesky represents more than just a replacement - it is a chance to rebuild social spaces with a less polarised, more discursive intent. Much of this is already there with its decentralised foundations, transparent moderation efforts, and a growing user base eager to cultivate meaningful conversations. In some ways, the platform appears like a rescue ship on the horizon, ready to save us from the hostile X. The spirit of sharing and connection appears to be alive there, and while no social media space is perfect, Bluesky offers a future shaped by those who seek connection over chaos.

Fail we may. Sail we must.

Here be dragons: Sandra Sinfield and Tom Burns, London Metropolitan University

During the pandemic we determined to find ways to make our online classrooms as active, creative and embodied as our face-to-face (F2F) classrooms had been. Where previously we had facilitated collage and making and drawing and writing to learn - with our ‘Dalek of Resources’ (Abegglen et al., 2020) wheeled into our bespoke classroom space to facilitate active learning in practice - now we had to break down all that we needed those resources for - and decide what we could ask participants to do instead in their own homes.

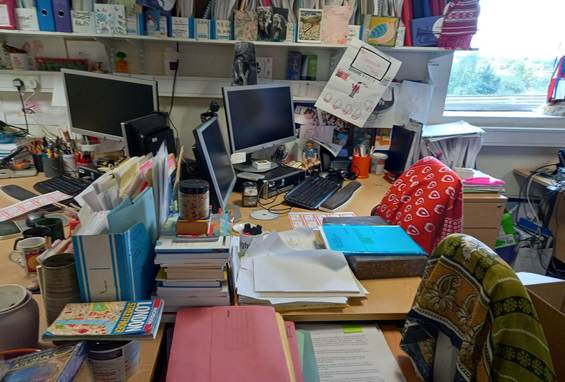

Figure 2. Our Dalek of Resources. Personal photograph by Tom Burns. Tom Burns CC BY 4.0 DEED.

Our Dalek contained magazines, scissors, glue for collage work - to realise unconscious thoughts about teaching and learning; sugar paper, chalk and felt tips - so that we could gather the tables into islands for group playful practice - and where the participants would find themselves drawing and annotating the paper - actively making their ideas visible and the learning conscious; we had textscrolls, blu tack and highlighters for collaborative reading - collectively exploring theory through the lens of this practical activity; we had the most bizarre range of stationery and clean recyclables for “making” activities… and yes of course we had Lego. Everybody must have Lego!

So, our at home lecturers were also invited to make a collage of themselves as a lecturer, a model of a typical student, and an assemblage representation of HE - and post pictures to the class Padlet: To seed discussion about how to make HE morph and flexibly expand to welcome our diverse students - and equally diverse lecturers. We challenged them to make blackout poetry to approach reading differently and more powerfully - and ‘found word’ poetry to realise that writing can be emergent: that we can write to learn rather than learn to write. We put them into breakout rooms and gave them a virtual ball of string or box of chocolates, board games or large rolls of paper - and invited them to design active and creative sessions for their own students.

And whilst we were ‘working away,’ they stole our offices - and we lost our resources. We did receive online tutorials on how to book and silently sit in anonymous, collective workspaces. But there would be no more Dalek and paint and sugar paper. No more fridge and microwave, kettle, and biscuits. No more pictures on the wall and journals, books, and articles to hand to seed brainstorming and writing with colleagues. No more bounty, no more human heart, and soul.

So, we kept our active, creative, and ludic PGCert classroom online. It was only on virtual seas that we could be as playful and embodied as we used to be F2F. It is only in cyber space that we can manifest the hope that our participants become buccaneers in turn, plotting a ludic course to richer and more active classrooms for their own students. Online, we provoke them to inhabit the postdigital classroom actively and creatively and in playfully embodied, and ‘appropriate’ low tech ways.

And that playful, colourful office - where did the treasure go? We rescued what we could - now safely stored away in a ‘cupboard of curiosities’ in our caravan by the sea:

Figure 3. Fragment of the former office space. Personal photograph by Tom Burns. Tom Burns CC BY 4.0 DEED.

Seeking solace in strange places: Rachelle Emily Rawlinson, Durham University

It is not unheard of to encounter turbulent seas and to have your voyage plagued by unpredictability. For my entire career I have existed in strange places of restructure, in academic and adjacent roles; but trusting in my compass to guide the path and help me to weather the storms.

What comes with uncertainty? Creativity, innovation, problem-solving. Or at least for me this is the case. So when plunged into a ‘new normal’ I embraced the opportunity to explore outside of the boat. Whereas previously I may have kept my ideas hidden, the unfolding of 2020 as a digital educator encouraged me to put all of my wares on display and throw caution to the wind (O’Brien & Farrow, 2020). This led not only to unexpected discoveries but new comrades.

As a fully remote worker I am in the truest definition hybrid. My physical self is in my home office with my two scallywags (dogs but I kind of wish I had a parrot; it would make this metaphor way more fun) but my mental self is digitally mediated through a computer screen. Intertwining technology into my reality allows me to exist in multiple worlds - creating a mixed reality self at the same time, which for me, is magical.

Figure 4. The scallywags themselves, Snake Breath Jan (left) and Whinin’ Deb Bones (right). Personal photo by Rachelle Emily Rawlinson. Rachelle Emily Rawlinson CC BY 4.0 DEED.

So where in these strange places did I find solace? Escape rooms! It surprises me as much as anybody else. What fun is there to find in locking people in a room you might think? Well, they are not literally trapped - do not worry! But what these prisons do offer is the thrill of a clue hunt, the spine-tingling adrenaline of a killer storyline. The camaraderie of coming together to problem-solve and do the seemingly impossible to solve puzzles and achieve a goal and - my favourite - experience surprises! Are you seeing why it appeals?

It was through the unexpected turbulence of a Microsoft Teams integration that I found my way to this island of solace. A way of mixing the seemingly unmixable - escape rooms and education.

During the pandemic I decided to invite some guests to explore my island and I realised in the process that I was creating a new normal, in a very distinct way. Instead of hiding behind policy, I was opening up creatively and encouraging others to explore beyond the bounds. Using technology in ways that they are not intended to be used. You could say that in some ways I was hacking the system. My small act of rebellion which gave control and encouraged creativity in an uncertain time.

Escape rooms have come to represent my postdigital classroom. A bit challenging, requiring problem-solving and the confidence to fail and try new approaches (Rawlinson & Whitton, 2024), but also surprising in the best possible ways. And although escape rooms felt like a new discovery, in some ways, I had been here all along.

Beyond the digital cave - Philosophical Pathways for AI in education: Marianthi Karatsiori, University of Macedonia

In Raphael's The School of Athens, philosophers gather in a vibrant intellectual exchange, each perspective adding depth to a collective pursuit of understanding. Today, we face a similar yet radically different scene: AI enters the educational landscape and postdigital classroom, promising - or threatening - to transform how we conceive of learning, knowledge, and human potential. How do we integrate AI into the fundamentally human process of education? Can machine learning algorithms truly engage with the nuanced, contextual, and deeply personal nature of knowledge acquisition? And most critically, how do we ensure that AI serves to expand human wisdom rather than replace human understanding? These are not merely technological questions, but profound philosophical challenges that strike at the core of what it means to learn, to teach, and to grow intellectually. As we stand at this technological crossroads, philosophical perspectives can become crucial navigational tools.

At the heart of this exploration lies a profound understanding of education as more than an individual pursuit - it is a deeply relational process of mutual responsibility. Each philosopher touched upon in this vignette points to a fundamental truth: learning is not merely about acquiring knowledge but about cultivating a sense of interconnectedness and care for others. In the context of AI, this responsibility becomes even more critical - challenging us to ensure that technological tools enhance rather than erode human connection. This responsibility extends beyond the classroom, challenging learners to see themselves as part of a larger human community. It asks not just what we can learn, but how our learning can contribute to the collective well-being, how it can transform not just ourselves, but the world around us.

Figure 5. Raphael School of Athens. Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ARaphael_School_of_Athens.jpg. CC BY-NC-ND.

This delicate balance between technological potential and human values demands a careful philosophical examination. The emergence of AI in education is not simply a technological upgrade, but a fundamental reimagining of the learning process. Just as the philosophers in Raphael's fresco challenged and debated existing paradigms of knowledge, we now face a similar moment of radical intellectual reconfiguration. AI presents us with an unprecedented opportunity to examine the very foundations of educational theory - pushing us to interrogate our most basic assumptions about learning, understanding, and human potential. By drawing upon the rich traditions of philosophical thought - from Plato's dialogic method to Freire's critique of oppressive educational systems - we can explore the values that should underlie postdigital future classrooms. It is not enough to simply ask what AI can do; we must critically examine what AI should do in the context of human learning and development. The stakes are profound.

AI has the potential to democratise education, personalise learning experiences, and unlock new pathways of intellectual discovery. Yet it simultaneously threatens to commodify knowledge, reduce complex human understanding to algorithmic processes, and further entrench existing social inequalities. AI invites a new kind of dialogue - one between machine intelligence and the human mind and heart. As we contemplate AI's place in learning, we find ourselves at a pivotal moment that echoes the foundational questions posed by the great thinkers: How does knowledge grow? What does it mean to understand? And how can the pursuit of wisdom be guided in a world where technology plays an increasingly prominent role?

Plato, through his Socratic dialogues, emphasised that education must guide people toward truth through dialectic reasoning. In The Republic (Reeve, 2004), he argues that true education involves guiding students towards knowledge and deep thinking through a relationship of trust between learner and teacher. Following this principle, he might view AI as a powerful tool for accessing information but would warn against mistaking this for wisdom. His allegory of the cave finds new relevance - would AI create new technological shadows that we mistake for reality? The challenge would be ensuring AI stimulates rather than replaces the critical dialogue essential to learning.

Aristotle's distinction in the Nicomachean Ethics (Crisp, 2014) between ‘techne’ (expertise) and ‘phronesis’ (enlightenment) provides a crucial framework for analysing AI. In Politics (Barker & Stalley, 1995), Aristotle argues that education is essential for implementing virtuous actions and therefore a social issue. AI might represent an unprecedented advancement in “techne”, but Aristotle would insist it must be balanced with “phronesis” - the practical wisdom to use it appropriately. His empirical approach would value AI's data-processing capabilities while maintaining that education must remain grounded in practical experience and moral judgment.

Rousseau, in Emile (1911), argues that education must be adapted to the natural stages of growth and it must be pleasurable. His naturalistic approach would likely view AI with scepticism, seeing it as potentially disconnecting learners from their natural development. However, given his emphasis on individualised learning, he might cautiously approve of AI that supports personalised educational paths while preserving the natural rhythm of human development.

Dewey's vision of education as fundamentally tied to democracy offers crucial insights. In Democracy and Education (Dewey 1985, p. 92), he argues that “democracy and education bear a reciprocal relation, for it is not merely that democracy is itself an educational principle, but that democracy cannot endure, much less develop, without education”. He would likely appreciate AI's potential to facilitate experiential learning but would insist it serve democratic ends by enhancing human interaction and problem-solving rather than replacing them.

Freire's Pedagogy of the Oppressed (Freire, 1972) challenges us to examine power dynamics in educational technology. His rejection of the ‘banking notion of education’ raises crucial questions about AI: Who controls these systems? Whose knowledge is privileged? In Pedagogy of Freedom (Freire, 2000), he emphasises that education must help people “reflect about their ontological vocation as subjects”. Following this principle, AI systems should empower learners as critical co-creators of knowledge rather than passive consumers of pre-programmed content.

Kant (1963, p. 61), writing about the ‘Philanthropin’ institute in 1776, envisioned education as preparing “citizens of the world”. His emphasis on universal moral law and human dignity, articulated in Critique of Pure Reason (Kant, 2003), would demand that AI systems treat learners as ends in themselves, not merely means to an end. The development of AI in education must serve what he termed in Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View (Kant, 2006) as humanity's highest potential.

These philosophical perspectives converge on crucial principles for AI in education: preserve human agency and critical thinking (Plato); balance technical capability with practical wisdom (Aristotle); respect natural learning processes (Rousseau); enhance rather than replace experiential learning (Dewey); empower rather than oppress learners (Freire); and uphold human dignity and autonomy (Kant).

These perspectives remind us that education must cultivate human capacities for empathy, critical reflection, and mutual understanding. Drawing on Nussbaum's (2010) model of human development, we must ensure that technological interventions in postdigital education do not diminish our ability to think critically and independently, to recognise the equal dignity of all people, to develop genuine concern for others' experiences, to imagine complex human stories beyond data, and to engage in meaningful democratic discourse.

For me, these foundational values become even more crucial as we face the major dangers AI presents to education: the potential erosion of critical thinking and genuine dialogue, widening equity gaps in access and opportunity, diminishment of human connection and development, challenges to knowledge verification and truth, privacy and data ethics concerns, threats to student and teacher autonomy, loss of cultural diversity in learning, and the possible weakening of education's role in democratic society.

In our current technological landscape, we face the twin risks of hyperindividualisation and hyperproductivity, both of which can diminish our essential human qualities. While our laptops give us the illusion of an open window to endless learning opportunities across the seas, true learning - like love - demands effort, patience, and time. Just as we must devote time to truly know and love another person, meaningful education requires deep engagement and human connection that cannot be rushed or automated.

The answer may lie in using technology not to replace but to expand our educational island, fostering human connections, shared wisdom, and collective and individual responsibility toward others, that have always been at the heart of true education. From ancient philosophers to modern educators, one truth remains constant: education is hard: a journey that requires dedication, perseverance, and often struggle.

Setting sail for uncharted territory: Anna Hunter, University of Law

In 2021, with the world still at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and HE at large still learning to navigate the choppy waters of online and blended learning, I applied for a new job. More than that, I moved to leave my employer of the past 15 years and set sail to uncharted territory. As the new role I envisaged for myself would involve teaching online permanently, and not as an anti-viral stop-gap, I included the following in my interview presentation:

In The New Learning is Ancient, Kathi Inman Berens (2012) writes, “It doesn’t matter to me if my classroom is a little rectangle in a building or a little rectangle above my keyboard. Doors are rectangles; rectangles are portals. We walk through.”.

When we learn online, our feet are usually still quite literally ‘on ground.’ When we interact with a group of students via streaming video, the interaction is nevertheless face-to-face. The web is asking us to reimagine how we think about space, how and where we engage, and upon which platforms the bulk of our learning happens.

In the UK, where I have conducted all of my teaching career, we are socially conditioned to experience classrooms as hierarchical spaces, no matter what strategies we might employ to address this. Online learning seems to offer a more democratic space, with fewer invisible boundaries governing participation. At the time I confidently claimed that I could not envisage ever going back to teaching the way that I had pre-pandemic. Now, four years later, it seems pertinent to reflect on this position in light of the postdigital classroom. Has my own move to permanently online practice broken down barriers in the way that I perceived it would?

The answer is ambiguous - yes, and also no. I find myself poised at a point of tension between what online learning is, and what it could be. Often, this dynamic is centred on the possibilities and limitations of the technology available; more than once the pedagogy has come second to the practicalities of what our systems can do.

I love being able to reach students and colleagues across the UK and even in different countries; we are connected in ways that were unheard of before 2020. And yet my heart beats faster when I find myself with a rare opportunity to be in the same physical space with people that I have only known through the ‘little rectangle above my keyboard’.

I am still searching for ways to emulate at a distance the creativity I imbued into my face-to-face teaching practices in my previous role, which is not to say that opportunities for creativity are fewer, rather they are different, and I am still learning where to find them. My students, who are also colleagues, are also still learning how to navigate the postdigital classroom. Some charge ahead willing to experiment, some still seek the comfort of the familiar. But would I go back to teaching the way I did beforehand? No – I would not. And though the maps may warn ‘here be monsters,’ the fear of the yet-to-be-known can also become the impetus to innovate.

I mean why on earth would anyone want to read what I write! I am a pirate: Emma Gillaspy, University of Central Lancashire

I sit here on my couch at home surrounded by technology - laptop on my knee, mobile phone there as a constant distraction feeding the inner imposter, smart speakers giving me some Lo-Fi concentration beats, smart lightbulbs providing a warm white feel to the room, paper-like tablet next to me (yet for some reason I still choose to type this via the keyboard on my laptop), and my smart watch buzzing to congratulate me on my movement - that must have been a particularly energetic keystroke! Such technology helps and hinders us every day, we control it and yet it controls us back (Lee, 2022; Nowotny, 2024). Are we symbiotic or is there a threatening undercurrent and if so, which way will it take us?

As I daydream through the process of writing this vignette, the real world around me fades away (cue wavy transitions) leaving an image of a merchant navy galleon named HE… Sneaking on board this neoliberalist HE trading ship I can see Commodore Metrics firmly at the helm: barking out the sector orders. Metrics runs a tight ship: How many students can we recruit? How many are we retaining? How satisfied are they with our service? How many leave our shores with enough skills to be successful in their careers? How do our numbers compare with our neighbouring trading outposts?

HE undercurrents such as this create winners and losers of the metrics game resulting in a competition over collaboration environment (Sarpong & Adelekan 2024). The numbers we need to keep abreast of, continue to grow, feeding the Kraken that is email - will we ever learn how to vanquish this beast that sucks hours from our days? Spotted by Metrics, I have a choice to either assimilate or reject the system (Mula-Falcón & Caballero, 2022). Resisting the pressure to join the formal ranks, I spot some fellow swashbuckler-types lurking around the edges.

Responding to the call for human connection, which feels even stronger since the pandemic, our ragtag crew jump ship, sailing the digital seas together to the promising new shores of Bluesky. In our creative crew we are able to be our congruent selves, celebrating diverse strengths and challenging each other to bring our very best to the world of facilitating learning in HE. This permission to unmask is visceral and powerful (Gillaspy et al., 2022) and without digital technologies we would not have been able to create this incredible tribe where we truly welcome learning from, with and about each other. We advocate moving beyond using technology for technology's sake, instead using it to create and foster human connection with our colleagues and learners. With the current worrying global push towards division and hostility, we have the opportunity to use our collective power to break down HE silos and role model collegiality.

Seeing academics and universities flee unethical social media platforms has been a heartening experience. There is good in our digital spaces and it’s critical we use these to be our true selves rather than trying to assimilate to any current or future system norms. Our tale is one of positive disruption, working at the edges to nudge the direction of the fleet of HE merchant ships. The ability to find commonality, to celebrate uniqueness, are the skills needed for HE to survive in our postdigital future. All are welcome on board this creative ship Unmasked (Figure 6). The only orders are that you drink up that learning me hearties! Now bring me that horizon, yo ho ho!

Figure 6. An AI-generated image of this vignette by Emma Gillaspy. Emma Gillaspy CC BY 4.0 DEED.

Sailing into the future: Sandra Abegglen, University of Calgary

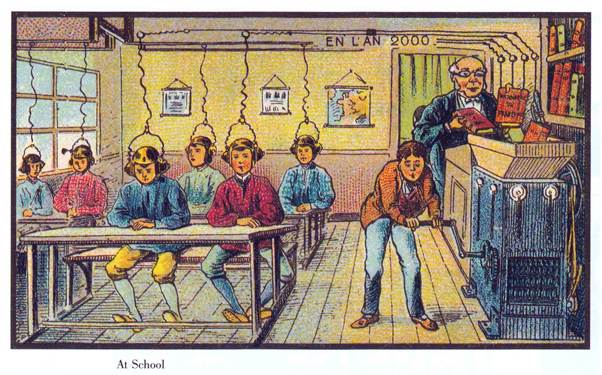

In 1900, a French toy manufacturer named Armand Gervais commissioned a series of illustrations to envision the world a century into the future. Created for the 1900 World Exhibition in Paris, these paper cards were initially designed to be tucked into cigarette boxes and later repurposed as postcards. The first fifty were crafted by Jean-Marc Côté, with subsequent contributions by other artists, resulting in at least seventy-eight cards - though the exact number remains uncertain, with some potentially still undiscovered. Each card captures an imaginative glimpse of life in the then-distant year 2000.

One particularly striking postcard depicts the ‘school of the future’, where students are plugged into a machine transmitting knowledge directly into their brains (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Côté, Jean-Marc, ca. 1900, At School. Source: https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/a-19th-century-vision-of-the-year-2000. CC BY-NC-ND.

This image invites reflection in our postdigital age: How much of this vision has materialised? And where did these early futurist buccaneers go astray? Moreover, as we stand in the 21st century, how do we imagine the future? Will classrooms in the year 3000 still rely on high-tech gadgetry, or will they evolve in ways that transcend mere technology? Can we still sail the old ship?

Despite technological advancements - from iPads to VR goggles, SMART boards to immersive reality screens - the underlying narrative of a ‘push-button’ education appears to persist. This paradigm prioritises knowledge transfer, correct answers, and behavioral conformity, echoing the vision presented in Arthur Radebaugh’s 1958 comic Closer Than We Think that appeared in the Chicago Sun Times from 1958-1963 (Novak, 2011):

Tomorrow’s schools will be more crowded; teachers will be correspondingly fewer. Plans for a push-button school have already been proposed by Dr. Simon Ramo, science faculty member at California Institute of Technology. Teaching would be by means of sound movies and mechanical tabulating machines. Pupils would record attendance and answer questions by pushing buttons. Special machines would be ‘geared’ for each individual student so he could advance as rapidly as his abilities warranted. Progress records, also kept by machine, would be periodically reviewed by skilled teachers, and personal help would be available when necessary.

This mechanised vision of education prompts another critical question: Where is the human, the humane, in this imagined future? Where is the making, doing, creating, and being - together? True learning involves more than knowledge transfer; it is about fostering curiosity, collaboration, and the joy of discovery. The pirates are needed more than ever!

I posit that in the postdigital classroom, where reductive notions of technology are pervasive, the challenge is to foreground the human dimensions of education, the humans on board. The revolution in learning will not come from gadgets alone but from reimagining education as a space for positive connection, creativity, and collective growth.

Conclusion

The article The Future Postdigital Classroom (Forsler et al., 2024) prompted us to start this journey, a treasure hunt exploring digital possibilities beyond the data-driven - and for curious adventurers and fellow travellers: academics, teachers, and technologists within HE. We understand that technologies are an integrated part of learning environments and practices: we are all postdigital now; and we wanted to collectively imagine what the future classroom might look like. What is this postdigital ‘now’ - and what could the future look and be like - in the best of all possible worlds? As pirates of the #creativeHE collective, we came together to sail forth, to discuss, theorise, imagine, reflect. At the same time, we felt the anchor of the past. For surely that is one of the problems with education - and HE: it describes itself as evidence-informed and research-led - but it is an amnesiac ‘industry’, constantly re-making itself by forgetting its past. So, now, as the tides of change become ever more turbulent, both in HE and the wider world, we seized the moment to reflect on the future postdigital classroom - not as a space dictated only by futurologists and technocrats, nor driven by denatured data and top-down managerialists, but as a dynamic environment where “appropriate technology” (Schumacher, 2011, p. 155) is reclaimed and reinvigorated by reinserting and reinstating the humane and where tech (both high and low - as appropriate) and human creativity intersect. Embracing this vision, we raised the telescope and set sail to explore, and make the invisible visible from personal standpoints and through vignettes, the contested terrain of HE.

We looked deep into the future by looking at the past, we heard the many voices over millennia calling for authentic, dialogic, and humane education. We washed up on recent shores, discovering pandemic viruses that changed us all together and yet kept us deeply rooted in realia. Together we have been online and offline and altogether hybrid - boarding a vessel, hoisting the sails… What has emerged is a map of experiences that let us travel from the ancient wisdom of Aristotle to the uncharted waters of Bluesky. We have discovered escape rooms and fellow travellers also juggling many digital gadgets and online tasks. We have wrestled with blu tack and collage materials in real life and swapped them for blu tack and collage materials in our online learners’ real homes. We have experienced the multiple tensions of the many technologies in our classrooms - and the many directives from sector drivers barking about the importance of metrics over lived experience - drown us in policy documents and emails - and drive us towards technological oblivion. We tell tall tales of our hopes and fears, grounded in our real teaching, learning, and assessment practices.

Whilst valorising (and we do have to shout loudly about this in our technocratic age) the power of drawing-, writing- and making- to learn, whilst celebrating paint and glue, sugar paper and scissors, we have all in diverse ways experienced the - paradoxical perhaps, given our piratical natures - liberation of technology in our own practices. However, that treasure has been unearthed in ways contrary and antithetical to Commodore Metrics and all the other commanders who want to surveille and control not just our unruly bodies - but our emerging academic minds and the very journeys we take. Collaborating sceptically and provocatively and in humane ways our vignettes celebrate and chart the potential of the postdigital classroom. We argue that both high and low tech can be harnessed for adventure in truly transformative ways, empowering learners and educators alike to navigate the complexities of our digital age with creativity, purpose, and a shared commitment to the common good.

Through these vignettes we traced a map of our and our students’ classroom lives (that through tech itself are now so deeply entangled with everything else we do). We attempted to wrestle back the compass that directs the good ship HE - away from the bureaucratic technocrats and those who have not set foot in a classroom - real or virtual - for many a long year. There be dragons!

Call to action

We are a motley crew of academics, teachers, researchers, and technologists, but fundamentally our practices are student-centred - seeking creative and liberatory practices that help all our students set sail on a more active adventure, a more interesting journey and a more authentic destination.

We encourage you to join us on our piratical voyage - so we can steer the postdigital ship together. Through small but mighty steps, we can make humane, technology-enabled teaching and learning the norm rather than just the realm of the creative pirates. Let’s assemble the crew - and set sail toward a more just and creative postdigital future. There are various digital spaces where we gather - #creativeHE, #LDHEN, #LoveLD, #LTHEchat - and imagine. Join us.

Whilst we in this piece address academics, we also invite you to team up with your students - inviting them to be part of the endeavour - as only collectively we can shape the postdigital classroom. We need everybody! We can’t find the treasure without you - and your students.

References

Abegglen, S., Burns, T., & Sinfield, S. (2020). Montage, DaDa and the Dalek: The game of meaning in higher education. International Journal of Management and Applied Research, 7(3), 224-239. https://doi.org/10.18646/2056.73.20-016

Abegglen, S., Burns, T., & Sinfield, S. (2022). Review of Michael A. Peters, Tina Besley, Marek Tesar, Liz Jackson, Petar Jandrić, Sonja Arndt, & Sean Sturm (2021). The methodology and philosophy of collective writing: An educational philosophy and theory reader Volume X. Postdigital Science and Education, 5, 248-257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-022-00310-7

Abegglen, S., Neuhaus, F., & Wilson, K. (Eds.) (2022). Voices from the digital classroom: 25 interviews about teaching and learning in the face of a global pandemic. University of Calgary Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781773852805

Agostini, E., Schratz, M., & Eloff, I. (2024). Vignette research. Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350299412

Andersen, C. U., Cox, G., & Papadopoulos, G. (2014). Postdigital research—editorial. A Peer-Reviewed Journal About, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.7146/aprja.v3i1.116067

Barker, E., & Stalley, R. F. (Eds.) (1995). Aristotle: Politics. Oxford World’s Classics. Oxford University Press.

Barnett, R. (2007). A will to learn: Being a student in an age of uncertainty. McGraw-Hill Education.

Berens, K. I. (2012, December 3). The new learning is ancient. New Media Curious. https://kathiiberens.com/2012/12/03/ancient/

Blaschke, L. M., & Hase, S. (2016). Heutagogy: A holistic framework for creating twenty-first-century self-determined learners. In B. Gros & M. Maina (Eds.), The future of ubiquitous learning: Learning designs for emerging pedagogies (pp. 25–40). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-47724-3_2

Burns, T., Sinfield, S., & Abegglen, S. (2023). Postdigital academic writing. In P. Jandrić (Ed.). Encyclopedia of postdigital science and education. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-35469-4_27-1

Carrigan, M. (2016). Social media for academics. Sage.

Coniff Allende, S. (2018). Be more pirate: Or how to take on the world and win. Penguin

Conger, K., & Mac, R. (2024). Character limit: How Elon Musk destroyed Twitter. Cornerstone Press.

Crisp, R. (2014). Aristotle: Nicomachean Ethics (2nd ed.). Cambridge Texts in the History of Philosophy. Cambridge University Press.

Cronin, C. (2017). Openness and praxis: Exploring the use of open educational practices in higher education. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(5), 15–34. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v18i5.3096

Cousin, G. (2009). Researching learning in higher education. An introduction to contemporary methods and approaches. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203884584

Davies, B., & Gannon, S. (2006). The practices of collective biography. In B. Davies & S. Gannon (Eds.), Doing collective biography: Investigating the production of subjectivity (pp. 1–15). Open University Press.

Dewey, J. (1916/1985). Democracy and education. In J.A. Boydston (Ed.), J. Dewey (Vol. 1), The middle works, 1899-1924. Southern Illinois University Press.

Dewey, J. (1900/1985). The school and society. In J.A. Boydston (Ed.), J. Dewey (Vol. 1), The middle works, 1899-1924. Southern Illinois University Press.

Fawns, T. (2018). Postdigital education in design and practice. Postdigital Science and Education, 1, 132-145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-018-0021-8

Forsler, I., Bardone, E., & Forsman, M. (2024). The future postdigital classroom. Postdigital Science and Education, 7, 682-689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-024-00488-y

Freire, P. (1972). Pedagogy of the oppressed. (Myra Bergman Ramos, Trans.). Herder.

Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of freedom: Ethics, democracy, and civic courage. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. https://doi.org/10.5771/9781461640653

Freire, P. (2004). Pedagogy of indignation. Paradigm.

Gillaspy, E., & Vasilica, C. (2021). Developing the digital self-determined learner through heutagogical design. Higher Education Pedagogies, 6(1), 135–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/23752696.2021.1916981

Gillaspy, E., Routh, F., Edwards-Smith, A., Pywell, S., Luckett, A., Cottam, S., & Gerrard, S. (2022). Hard graft: Collaborative exploration of working class stories in shaping female educator identities, PRISM: Casting new light on learning. Theory & Practice, 5(1), 82–96. https://doi.org/10.24377/prism.ljmu.0401219

Greene, M. J. (2014). On the inside looking in: Methodological insights and challenges in conducting qualitative insider research. The Qualitative Report, 19(29), 1–13. http://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol19/iss29/3

Jandrić, P., Luke, T. W., Sturm, S., McLaren, P., Jackson, L., MacKenzie, A., Tesar, M., Stewart, G. T., Roberts, P., Abegglen, S., Burns, T., Sinfield, S., Hayes, S., Jaldemark, J., Peters, M. A., Sinclair, C., & Gibbons, A. (2023). Collective writing: The continuous struggle for meaning-making. In Postdigital Research: Genealogies, Challenges, and Future Perspectives (pp. 249-293). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-31299-1_14

Jandrić, P., Knox, J., Besley, T., Ryberg, T., Suoranta, J., & Hayes, S. (2018). Postdigital science and education. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 50(10), 893–899. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2018.1454000

Kant, I. (1963). Essays on the philanthropists. In H. H. Groothoff & E. Reimers (Eds.), Ausgewählte Schriften zur Pädagogik und ihrer Begrundung [Selected writings about education and its foundations]. Paderborn, Schöningh.

Kant, I. (2003). Critique of pure reason (Revised ed.). Palgrave MacMillan.

Kant, I. (2006). Kant: Anthropology from a pragmatic point of view. Cambridge University Press.

Kara, H. (2020). Creative research methods: A practical guide (2nd ed). Policy Press. https://doi.org/10.56687/9781447356769

Lapadat, J. C. (2017). Ethics in autoethnography and collaborative autoethnography. Qualitative Inquiry, 23(8), 589–603. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800417704462

Lederman, N. G., & Niess, M. L. (2000). Technology for technology's sake or for the improvement of teaching and learning?. School Science and Mathematics, 100(7), 345-348. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1949-8594.2000.tb18175.x

Lee, E. A. (2022). Are we losing control?. In H. Werthner, E. Prem, E. A. Lee, & C. Ghezzi (Eds.), Perspectives on digital humanism. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86144-5_1

Mula-Falcón, J., & Caballero, K. (2022). Neoliberalism and its impact on academics: A qualitative review. Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 27(3), 373–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/13596748.2022.2076053

Murray, E. (2021, February 17). Andrew Weatherall’s 'Fail we may, sail we must' origin story uncovered by Irish radio DJ. DJ Mag. https://djmag.com/news/andrew-weatherall-s-fail-we-may-sail-we-must-origin-story-uncovered-irish-radio-dj

Noble, D. (2003). Digital diploma mills. In Steal this university (pp. 39-54). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203465493-4

Novak, M. (2011, August 24). The push-button school of tomorrow (1958). Paleofuture The history of the Future. https://paleofuture.com/blog/2011/8/24/the-push-button-school-of-tomorrow-1958.html

Nowotny, H. (2024). The illusion of control: Living with digital others. Global Perspectives, 5(1), 117336. https://doi.org/10.1525/gp.2024.117336

Nussbaum, M. C. (2010). Not for profit: Why democracy needs the humanities. Princeton University Press.

O’Brien, R, E., & Farrow, S. (2020). Escaping the inactive classroom: Escape rooms for teaching technology. The Journal of Social Media for Learning, 1(1), 78-93. https://doi.org/10.24377/LJMU.jsml.vol1article395

Pepperell, R., & Punt, M. (2000). The postdigital membrane: Imagination, technology and desire. Intellect.

Punch, K. (2014). Introduction to social research: Quantitative and qualitative approaches. Sage.

Rawlinson, R, E., & Whitton, N. (2024). Escape rooms as tools for learning through failure. Special Issue: Educational Escape Rooms (EERs). Electronic Journal of e-Learning, 22(4), 19-29. https://doi.org/10.34190/ejel.21.7.3182

Reeve, C. D. (2004). Plato: Republic. Hackett.

Robinson, K. (2016). Do schools kill creativity. TED. https://speakola.com/ideas/sir-ken-robinson-do-schools-kill-creativity-ted-2006

Rousseau, J.-J. (1911). Emile. (B. Foxley, Trans.). Dent.

Sarpong, J., & Adelekan, T. (2024). Globalisation and education equity: The impact of neoliberalism on universities’ mission. Policy Futures in Education, 22(6), 1114-1129. https://doi.org/10.1177/14782103231184657

Schumacher, E. F. (2011). Small is beautiful: A study of economics as if people mattered. Random House.

Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research. Sage.

Tattersall, A. (2024, September 5). If academic X is sinking, where are research organisations going? LSE Impact Blog. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2024/09/05/if-academic-x-is-sinking-where-are-research-organisations-going/

Weller, M. (2011). The digital scholar: How technology is transforming scholarly practice. Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781849666275

Wheeler, V. (2018). Foundations of a bricolage method: Using learning stories for the co-production of curriculum design, impacting experiences of learning difference within higher education. Journal of the Foundation Year Network, 1, 37-49.