Registered replication reports in the classroom

Steven Verheyen1, Lea Baumann1, Timothy Chomicz1, Alex Gordzievskaia1, Renée Gouw1, Florence Jacquorie1, Katharina Kappel1, Hanna Karasek1, Lucie Sophie Kloss1, Hannah Klug1, Jule Joy Koye1, Eva-Lotte Martini1, Clara Marie Schaake1, Ela Senbak1, Jenny X. Shu1, Deniz Sidi1, Maria Barbara Smorczewska1, Marios Srouzi1, Yoana Staykova1, Júlia Štefunková1, Laura-Sophie Teichert1, Adarshni Thakoerdin1, Fréderique Eva Tienhoven1, Claudia Torres Pérez1 and Minh Tran1

1 Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

Abstract

Background: Registered Reports are an emerging publication format, which emphasizes methodological rigor over results. The research protocol, including methodology and planned analyses, is peer-reviewed and provisionally accepted before the study is conducted and thus regardless of the results. Integrating this format into education allows one to teach research skills when data collection is infeasible.

Objective: To reflect on the implementation of Registered Reports for replication research in an undergraduate psychology methods course.

Method: A five-week course was conducted where students developed Stage 1 Registered Reports proposing to replicate published findings. Afterwards, the students collectively reflected on the merits of Registered Reports in education through a series of consensus meetings held during a Paper-in-a-Day (PiaD) workshop, which also served as a collaborative writing activity for this paper. PiaD workshops are intensive, collaborative sessions where non-academics work together to conceptualize, draft, and often complete a research paper within a single day.

Results: The students indicated that Registered Reports scaffolded their research skills, enhanced their motivation, and instilled open science values in them. They also reported gaining practical insights into reproducible research practices but worried about the necessary support to continue applying them and expressed concerns about public pre-registration, citing fears of criticism.

Conclusion: Registered Reports are valuable for teaching research methods, particularly in courses where data collection is impractical. However, institutional support and curriculum-wide integration are essential to sustain the benefits they provide.

Teaching Implications: Instructors should leverage the full feedback opportunities of Registered Reports and be mindful of the hidden costs of engaging students in open science practices. PIAD workshops can be explored as standalone educational activities.

Keywords

open science, open education materials, pre-registration, replication, paper-in-a-day (PiaD)

Introduction

Since the 2010s, the issue of non-replicability has become apparent across scientific fields (Hicks, 2023; Nelson et al., 2021). The problem first emerged in psychology where it was coined ‘the replication crisis’ and has been extensively studied and discussed ever since (Malich & Munafò, 2022; Shrout & Rodgers, 2018; Wiggins & Christopherson, 2019). The nature of this crisis is two-fold: Not only are replications very rarely undertaken (e.g., Clarke et al., 2024; Kamermans et al., 2025; Makel et al., 2012), large-scale investigations have indicated that a large proportion of replications produced weaker evidence compared to the original studies (e.g., Camerer et al., 2018; Open Science Collaboration, 2015). This suggested that publication bias and the file-drawer problem (McAleer & Paterson, 2021) were more pervasive than previously thought and overall raised questions about the reliability of the psychological literature. These questions are increasingly being asked about other disciplines as well (see, e.g., Makel & Plucker, 2014; Perry et al., 2022; and Wiliam, 2022, on educational science). As a result, in the years that followed research practices were reevaluated, and an increased focus was placed on implementing open and responsible science practices in institutions and among individual researchers, ultimately leading to a positive shift in science culture (Korbmacher et al., 2023). Registered Reports are among the changes made to build a more reliable scientific literature.

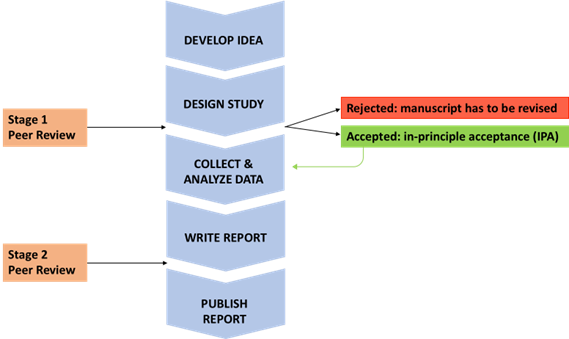

The Center for Open Science (2019) defines Registered Reports as a publishing format focusing on the importance of the research question and the quality of methodology by integrating peer review prior to data collection (https://www.cos.io/initiatives/registered-reports). While Registered Reports are increasingly used for qualitative research as well (Karhulahti et al., 2023; McAleer & Paterson, 2021), they have been used most extensively for hypothesis-testing quantitative research, which is also the focus of this paper. A Registered Report that is submitted for Stage 1 Peer Review (Figure 1), includes an Introduction, a Method section, and potentially results of pilot studies that motivate the research proposal. This Stage 1 manuscript undergoes peer review and after one or several peer review rounds either receives in-principle acceptance (IPA) or is rejected. By providing IPA, the journal that organizes the peer review commits to publish the final paper, regardless of whether the predicted results are supported, under the condition that researchers adhere to the protocol laid out in their Stage 1 manuscript (Chambers & Tzavella, 2021). By disconnecting the decision to publish a manuscript from the results it presents, Registered Reports aim to eliminate publication bias and questionable research practices such as p-hacking, selective reporting, and HARKing. However, flexibility to conduct and report exploratory, unregistered analyses and their findings is still granted. If researchers receive IPA, they can carry out the study to then submit a Stage 2 manuscript containing the Introduction and Methods from the Stage 1 manuscript along with the Results and Discussion. The Result section comprises the confirmatory pre-registered analyses that were laid out in the Stage 1 manuscript together with any additional unregistered analyses under a separate section called ‘Exploratory analyses’. The analyses can pertain to new primary data or existing secondary data, as long as the data are only collected or accessed after IPA is obtained. Researchers are encouraged or required to share their obtained data together with their data analysis scripts in a freely accessible database such as OSF or Figshare. The Stage 2 manuscript undergoes peer review as well, preferably by the same reviewers who approved the Stage 1 manuscript and who can check whether the authors complied with the initial plans and drew appropriate conclusions. Once the Stage 2 manuscript is approved, it is published. The splitting of peer review into two stages differentiates Registered Reports from pre-registration, thereby shifting the focus to the alignment and suitability of the research questions and procedures, and masking their evaluation from research outcomes (Chambers & Tzavella, 2021).

Registered Reports can be used to address novel research questions but are also ideally suited for replication research (Allen & Mehler, 2019). When a particular study design and its ensuing results are available from the replication target, it becomes easier to draft a Stage 1 manuscript detailing planned methodological decisions such as the target effect size and sample size. The authors of the target study can also be involved in the peer review of the Stage 1 manuscript, providing the replicators with undisclosed background information that might be crucial for replicating the original finding. Importantly, the involvement of the original authors at this stage ensures that they cannot later engage in gatekeeping of unfavourable outcomes (e.g., failures to replicate) because they signed off on a particular research plan beforehand.

Clinical Registration Reports have long been used by medical researchers, and an early version of Registered Reports was already implemented at the European Journal of Parapsychology in 1976 (Wiseman et al., 2019), but it took a while for Registered Reports to gain a foothold in other fields. In 2012, the term was coined by Chris Chambers and introduced in two journals, Cortex and Perspectives on Psychological Science, as a method to increase the replicability of existing research (Chambers, 2013). Following a number of adaptations and expansions, Registered Reports are becoming a more conventional practice (Chambers & Tzavella, 2021). The format is currently being offered by more than 300 journals (Lin et al., 2024) and specific platforms such as PCI RR (Eder & Frings, 2021) have been set up to support authors and journals in the publication of Registered Reports.

Even though there are ongoing discussions regarding the Registered Reports format, including a need for more transparency, standardization, and efficiency, its benefits appear to outweigh any negative aspects (Chambers, 2019). In a study by Scheel et al. (2021), results of published Registered Reports were compared to a random sample of standard reports finding 96% positive results in standard reports but only 44% positive results in the Registered Reports (see Allen & Mehler, 2019, and Wiseman et al., 2019, for similar results). The lack of negative findings in the standard literature compared to Registered Reports is explained by the latter’s reduction of publication bias as well as Type I error inflation. Authors are not incentivized to present a hypothesis derived from the data as though it was conceived a priori, while the separation of exploratory and confirmatory hypothesis testing is promoted (Mehlenbacher, 2019). Additionally, Replication Reports discourage selective reporting to achieve significance and enhance reproducibility through rigorous standards for statistical power. It should then not come as a surprise that researchers perceive Registered Reports to be of higher quality than non-Registered Reports (Soderberg et al., 2021) and that Registered Reports bolster confidence in the reported findings (Alister et al., 2021).

Registered Reports also serve a crucial pedagogical role by reinforcing the importance of precise a priori predictions and valid statistical practices that improve the study design at an early stage and increase authors’ confidence in their work (Hukkelhoven, 2022). In what follows, we will focus on the pedagogical benefits of Registered Reports for quantitative (hypothesis-testing) replication research and refer to this type of Registered Reports as Registered Replication Reports. This should not be confused with multilab registered replication reports where multiple laboratories conduct the same study with a pre-established protocol clarifying the specific methods (Simons et al., 2014). Those studies aim to combine resources and collect data from large samples in order to establish the presence or absence of an effect with high certainty (Lewis et al., 2022). Here, we focus on the use of the Registered Reports format to conduct a replication of an already published study.

Figure 1. Registered Reports workflow

|

Registered Reports in the classroom

The replication crisis has questioned the validity of findings of previous studies and even entire fields (e.g., Anvari & Lakens, 2018; Wingen et al., 2020). It is now generally acknowledged that it is important to teach students about the problems that led to the replication crisis and to equip them with the necessary tools to not only avoid making the same mistakes over again, but to do better than previous generations (Chopik et al., 2018). That is why many departments are now teaching students how to conduct replications, pre-register their studies, and make their materials, analysis scripts, and data FAIR (e.g., Grahe et al., 2012; Hawkins et al., 2018; Wagge et al., 2019).

Frank and Saxe (2012), for instance, have proposed that conducting replications be implemented in the standard training of undergraduate and graduate students. Based on their experiences teaching students at MIT and Stanford, Frank and Saxe report three benefits of having students conduct replications (see also Stojmenovska et al., 2019, for similar arguments). First, since the design and methodology have already been figured out by the original authors, this task is not too overwhelming for students who are still in the process of learning. It allows students to understand the decisions that the researchers of the original paper made (Janz, 2016). Second, the advantage of replicating recent studies is that the topics are likely valuable and interesting to the community. Lastly, the students iteratively advance science, which is both helpful for the field and rewarding for the students. The idea that students are motivated to conduct replication research is also supported by the fact that students undertake these assignments very carefully (Frank & Saxe, 2012).

Jekel et al. (2019) subscribe to the observations by Frank and Saxe (2012). They too argue that conducting a completely novel study might overwhelm students. Conducting a replication based on a pre-existing design and statistical analyses, on the other hand, makes for a meaningful and authentic, yet feasible assignment. Students have the opportunity to focus their attention on learning useful skills, such as improving their methodological and statistical abilities and knowledge, in a hands-on manner. At the same time, they undertake the replications that seasoned researchers are reluctant to do, although replications are considered the staple of science (e.g., Cohen, 1994; Popper, 2005; Roediger III, 2012). Students’ replications can contribute to the confidence one has in a finding (e.g., Perrault, 2022) and/or indicate limits to its generalizability (e.g., Korkmaz et al., 2023). Furthermore, conducting a replication might also provide an additional incentive to students. While other student assignments, such as literature reviews, rarely end up being published, a replication study that is properly done and adheres to the scientific standards, may have a better chance of being published (Jekel et al., 2019; Wagge et al., 2019). This elevates the students’ work from a mere assignment to a potential contribution to the scientific literature and a meaningful addition to their academic resume.

Others have argued for the value of teaching pre-registration in the (under)graduate curriculum (Blincoe & Buchert, 2019; Pownall, 2020; Pownall et al., 2023b). Much like replications, pre-registrations are considered useful scaffolds to learn to conduct better research. Pre-registration forms can help students plan their research projects better (in that they ensure that important considerations are not overseen) and support the reporting (in that they provide both a reporting template and signal all the information that needs to be provided; Blincoe & Buchert, 2019). Indeed, students who pre-registered their research projects reported that it improved both the rigor of their work as well as the organisation of their reports (Pownall et al., 2023b). More generally, students who pre-registered their research projects were found to have a better understanding of open science concepts and indicated that it discouraged the use of questionable research practices and motivated them to pre-register future projects (Pownall et al., 2023b).

Introducing students early in their education to open and responsible research practices such as pre-registration and replication, may thus be a good way to prepare students for a field that is becoming more open (Pownall et al., 2023a) in that it allows them to experience how contemporary science is conducted (Frankowski, 2021). This in turn may benefit the field as a whole if the next generation of researchers becomes more aware of the importance of methodological soundness, transparency, and replication, and is sufficiently critical towards earlier findings (Jekel et al., 2019). Finally, it has been argued that engaging students in open science practices improves their critical thinking (Bukach et al., 2021) and bolsters a positive attitude toward research (Pownall et al., 2023a). Whereas teaching students about the replication crisis and questionable research practices may give them a negative impression of their field of study, having them learn about and practice open science may increase students’ trust in research.

In what follows, we present the outline of a course in which students are taught about the problems that led to the replication crisis in psychology, and the open and responsible science solutions that have been proposed to combat this crisis. The course sees students engage in a Registered Replication Report. That is, as a final assignment for the course, they are expected to draft a Stage 1 Registered Report detailing how they would replicate a published study. The Registered Replication Report assignment is meant to combine the pedagogical benefits of conducting replication research and engaging in pre-registration outlined above, seeing that a Stage 1 Registered Report may be viewed as a narrative or open-ended form of pre-registration. The assignment is considered to be particularly interesting for short research courses, where there is no time to actually collect data, or in case there are other practical or ethical considerations that prevent students from collecting actual data. Although it does not see students experience the process of data collection and analysis, it does require them to go through the most important steps of the research cycle in that they nevertheless need to specify how they would go about collecting, analyzing, and interpreting the data. We report the students’ experiences with the course and use them to formulate recommendations and alternatives. A notable feature of this report is that it has been jointly drafted by students in the class and the course coordinator using the Paper-in-a-Day (PiaD) method (Baron et al., 2020; Larsen et al., 2024), which in itself is a promising education method to engage students with research. We start by outlining the course, after which we turn to the documentation of the students’ experiences through the PiaD method.

The course

Positioning of the course in the curriculum

The course ‘Performing Replications of Psychological Research’ is offered to third-year Bachelor of Psychology students at Erasmus University Rotterdam (The Netherlands) who chose to specialize in Brain and Cognition. It is a 2 ECTS course that runs in parallel to a 5 ECTS course over 5 weeks. During the first two years of the bachelor's degree, students took mandatory courses that provide a basis for the course (statistics, psychometrics, academic writing, and research methods). Anecdotally, students who opt for the Brain and Cognition specialisation tend to have a strong interest in doing research. The course is meant to provide them with hands-on practice in this regard and to offer them insight into the professional field of scientific research. It introduces students to open and responsible science and acquaints them with metascientific tools such as pre-registration, Registered Reports, and the Open Science Framework. Its design is based on the conviction that the best way for students to learn about open and responsible research practices is to engage in them (Blincoe & Buchert, 2019; Pownall, 2020), and that by doing so, students can effectively contribute to science (e.g., Frank & Saxe, 2012; Grahe et al., 2012; Hawkins et al., 2018; Heyman & Vanpaemel, 2022; Jekel et al., 2019; Wagge et al., 2019). The latter is stimulated by offering students the option to post the research proposal they develop during the course on the Open Science Framework and/or to effectively execute it for their bachelor’s thesis later in the academic year.

Learning goals

The general objective of the course is for students to write a Stage 1 Registered Replication Report based on a published article. More specifically, students have to articulate why conducting a replication of the selected target study is interesting, design an appropriately powered replication study, and formulate a complete analysis plan. There are also learning goals for each skills group meeting: students should be able to identify the questionable research practices that led to the replication crisis in psychology and explain the open science practices that have been proposed to remedy the replication crisis; students should also understand why and how replications are conducted and be able to critically assess scientific publications for limitations. A secondary objective of the course is to enthuse students about open and responsible science and to equip them with the means to conduct better original research (e.g., by practising open science in their bachelor or master thesis).

Learning activities

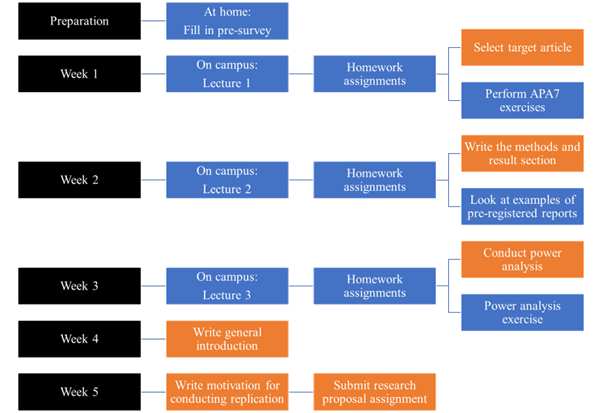

To achieve these objectives, the course utilizes various learning activities, including three 3-hour skills group meetings. Before each meeting, students are assigned readings and preparatory tasks to prepare for the topics that will be discussed. The first meeting focuses on problems relating to research and publication processes, while the second meeting concerns solutions such as practising open and responsible science. The last meeting is specifically on registered reports and conducting a priori power analyses. During each meeting, students are given exercises to apply their newfound knowledge. Additional materials, such as optional readings on the teaching philosophy, examples of Registered Replication Reports, and further readings on open science, are also provided to help students achieve the learning goals. The examples of Registered Replication Reports comprise both published studies and particularly good student assignments from previous cohorts. The latter are provided to give students a good idea of the expectations for the course and because previous students indicated many published Registered Replication reports to be challenging to process because they tend to be quite technical. For a general overview of the course, please refer to Table A1 and Figure A1 in the Appendix. All the teaching materials are publicly shared through the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/wab9u/).

Assessment

Students self-assess the skills group-specific learning goals by discussing case studies at the end of each meeting. Only the general objective of the course is formally assessed. The assignment for the course comprises a Stage 1 Registered Replication Report on one of several provided target articles. The reports are to be written individually, and the final grade is based entirely on the report’s quality, which is assessed by the course coordinator through a rubric. Students are provided with multiple example reports and a manual specifying the expected outline and the assessment criteria. The manual elaborates on the different elements of the rubric and indicates how to avoid common mistakes. To ensure the correct use of APA guidelines (10% of the grade), students are provided with a template with the necessary components: a title page, introduction section, method section, results section, reference list, and two appendices. The introduction (30%) is meant to include a description of the general phenomenon and the target study, as well as a hypothesis and motivations for conducting the replication. In the method section (40%), students are asked to explain the materials and procedure of the target study in detail and to propose a target sample size based on an a priori power analysis. A plan on how to analyze the data, including inclusion and exclusion criteria, is to be elaborated on in the results section (20%). The Appendix contains the details of the power analysis. Students must indicate their willingness to share their work through the Open Science Framework (see Appendix). The reports of students who were willing to do this, can be found at https://osf.io/wab9u/. Students are assessed independently of their willingness to publicly share their work.

Method

This section describes how the course coordinator and the students jointly reflected on the course, and reports how this paper, detailing the outcome of this reflection, came to be.

Paper-in-a-Day method

Paper-in-a-Day (PiaD) is a newly developed approach towards research engagement which is tailored to practitioners who are not active in the research field on a daily basis (Baron et al., 2020; Larsen et al., 2024). It brings people together around a shared topic to write a scientific paper within one day. It aims to improve confidence in one’s research skills, encourage collaboration, and provide an opportunity to practice and implement scientific practices related to publications. Here, we adopted it to have undergraduate psychology students discuss and evaluate a course they took part in.

The PiaD method, as its name states, is supposed to be conducted in one day (Larsen et al., 2024). If time constraints arise, it can, however, be divided into separate parts conducted on consecutive days. Nonetheless, it is important that the meetings are right after each other to keep the general attitude towards one, cohesive group assignment. Participants need to be interested in research, but there is no requirement for them to have extensive research experience. Depending on the number of participants and their preferences, participants can be assigned to different groups (Baron et al., 2020; Larsen et al., 2024). The method is fairly adaptable. It can not only be adjusted in terms of timeframe, but also in terms of the type of academic paper that is produced and the general discussion topics. However, there are certain elements which consistently recur (Larsen et al., 2024). The PiaD meeting should comprise of small group work (divided depending on the section of the paper), whole group discussions, and individual writing. Those activities can follow various orders and can appear in different ratios depending on the need in the specific PiaD meeting. The research question and any preliminary data to be used should be established before the meeting. Participants should be made aware beforehand of the amount of input they are going to have in the production of the complete article, as well as how they will be credited in the final paper.

According to the PiaD model, there are two distinct roles which need to be established to initiate PiaD (Larsen et al., 2024). The first role is that of the facilitator. The facilitator is responsible for establishing the location and date of the meeting, identifying participants, and maintaining communication with them so that everyone knows the details of the meeting and is aware of any necessary preparations. During the meeting itself, the facilitator establishes the goals for the meeting and presents them to the participants. The facilitator is usually also responsible for submitting the paper for publication after the meeting. The other role is that of data manager. This function mostly comprises handling the data, which will be used for the paper. It is important to note that such data can take on distinct shapes, such as empirically collected behavioral data, or already existing articles, meta-analyses, or systematic reviews. One person may take on both of these roles. Here, the course coordinator (SV) acted as facilitator, while three students (HK, LSK, AT) jointly took on the role of data manager. They were responsible for obtaining and synthesizing the students’ perception of the course. The course coordinator/facilitator (SV) was deliberately not involved in this process. The remainder of the students participated by contributing to specific sections of this paper (see below for details).

Consensus method

Developing coherence in a paper requires a shared understanding of the purpose and motives (Wodak et al. 2011). Consensus was established among the participating students through two periodical whole-group consensus meetings, where participants could produce decisions (Fink et al., 1984). These meetings were meant to establish an overall agreement on the perception of the third-year bachelor course the students had taken. The consensus meeting chairs facilitated discussions and encouraged students to voice their opinions on the benefits (consensus meeting 1) and downsides (consensus meeting 2) of using Registered Replication Reports in the classroom. There was also room to discuss the course's overall format and resources in both consensus meetings. It is important to note that the course coordinator (SV) was not part of this activity. It was fully led by the student participants.

Procedure

The course coordinator (SV) acting as facilitator offered all students in his course the opportunity to participate in a voluntary PiaD workshop to be held after the course had ended. His purpose was threefold: (i) to have students provide input on the course he had taught, (ii) to try out the PiaD method with undergraduate students, and (iii) to provide students with experience writing and submitting an academic paper and potentially boosting their resumes.

Of the 58 students taking the course, 24 signed up for the workshop (41%) indicating their preference to work on a specific section of this paper. They are all listed as co-authors. Co-authorship on the paper was thus dependent on participation in the PiaD workshop and the corresponding contribution to the paper, and not in any way on students’ performance in the course or their willingness to share their assignment online. The workshop started with a short kick-off presentation by the course coordinator/facilitator, where he introduced the goals and schedule for the day. After the kick-off, the student participants split into two smaller groups to discuss the benefits of Registered Replication Reports for education. Each consensus meeting was chaired by a student who had signed up to write the results section. This first consensus meeting was about 30 minutes long. After discussing the benefits in two groups, the chairs exchanged notes to generate a consensus statement. In the meantime, the remaining students started to plan their respective sections of the paper. They met with the other students working on the same section and discussed the process and the envisioned structure. The different groups looked for resources and some already started writing their sections. The facilitator visited the groups and checked in with the participants in case they had questions.

After lunch, two new consensus meetings of about 30 minutes were held. This time, the groups talked about the downsides of using Registered Replication Reports in the classroom and how these can be remedied by changes and/or alternatives. After the meetings, the chairs again compared notes while the other students worked in their respective groups or individually on writing the various paper sections. During this time, the course coordinator answered any questions or unclarities. When everyone was done writing their parts, the course coordinator held a closing session, where we looked back and reflected on what was done, and discussed the remaining steps. The entire PiaD workshop took 7 hours, including one hour of lunch.

After the meeting, the course coordinator added anything that was still missing and edited the paper for consistency. Then everyone reread it, gave suggestions for improvement, and finally approved the paper for submission. The course coordinator was responsible for submitting the paper for publication and keeping all contributors informed about the editorial process. After peer review, the course coordinator revised the paper together with volunteering students. During this stage, student quotes in support of the main findings were added. All co-authors approved the revised version for submission.

Results

Course evaluation

The students found the learning goals clear and indicated they clearly conveyed what was expected of them. They indicated that these goals naturally followed the more theoretical goals they needed to obtain in previous courses and were also forward-looking in that they signalled what is expected of a future researcher. The students were positive about the structure of the course and the learning activities, which they described as engaging, offering the right tools to make their individual reports achievable, as well as supporting their skills development toward their thesis later that academic year [1, 2]. They regarded the assignment as highly meaningful, allowing them to practice research skills they would need in later stages of their academic career in a structured manner. The fact that the assignment mimicked the real-world process of conducting research enthused them [2, 3].

[1] “The learning activities were clearly constructed in the course of five weeks. Even though the time span was short, the activities organized made it meaningful and practically oriented. By building from problem identification to problem solution, they offered an open space for discussion among peers who are connected by their shared goal of becoming researchers and contributing to science in a fair and honest way.”

[2] “Reflecting on your own personal motivations to conduct a replication report after three weeks of discussing with peers facing similar challenges, makes you assign a meaning to it, making it more engaging, and somehow easing the pressure typically associated with an academic assessment.”

[3] “The assessment was a very logical ending to the course. I felt that I could use all the skills I had learned while writing a Registered Research Report and during it I felt that it was already a contribution to the scientific community. Going through all the stages of a Stage 1 Registered Replication Report didn't feel as daunting as before starting the course. I would say it also increased the likelihood of considering writing more Registered Replication Reports or conducting replications later in our careers. While I felt many students were rather reserved towards writing a whole report by themselves, being led through the course and all the stages so well resolved all those thoughts.”

Benefits of Registered Replication Reports

In the consensus meetings on the perceived benefits of Registered Replication Reports for education, the topic of open science was a recurring one. Students indicated to have become more aware of the importance of scientific integrity through the course [4, 5, 7]. It instilled the values of open science in them and encouraged them to contribute to open science [5, 6, 7]. That is, they indicated that the conveyed knowledge could also be used when they would conduct research themselves in the future (e.g., in their bachelor’s thesis). The students indicated that by incorporating the values of open science at the beginning or prior to their academic career, they would be more likely to adopt these practices and thus produce more reliable studies in the future [5, 6, 7].

[4] “The course offered a well-balanced combination of theoretical and practical content, which helped me internalise and practice the principles of open science.”

[5] “I appreciated the introduction to the open science community at the bachelor level. Learning about its principles early in our academic careers sets a strong foundation for our future work and raises awareness about our responsibility in research practices. I am very grateful to have taken this course as it has provided me with tools and confidence that will serve me well in my future academic career.”

[6] “The course had a lasting impact on me. I approach research and academic literature more critically, paying closer attention to methodological transparency. Also, I now check whether the universities I am applying to explicitly mention open research and good research practices.”

[7] “The course itself is future oriented in two ways. (i) The course prepares the students for their own future research work by teaching skills and mindsets that are directly applicable. (ii) The future of research and science itself. Preregistrations and open science practices are becoming more prevalent and common.”

Besides the positive consequences of open science, the negative qualities of non-open science were discussed as well. When there is a lack of clear procedural guidelines for scientists to follow, it is tempting for researchers to conduct studies in dishonest manners. Such practices threaten the reliability of science and the scientific community. Implementing Registered Reports in the classroom can be seen as a means of discouraging questionable research practices. Presenting and evaluating studies prior to data collection directs the focus of (student) researchers to the actual methods and implications of the study, instead of on producing significant results [8, 9, 10].

[8] “The skill group meetings provided us with the necessary background knowledge about what the replication crisis is, where it emerged from and how to identify questionable practices within research papers.”

[9] “The skill group sessions provided us valuable guidance in identifying questionable research practices and understanding what the replication crisis is, how it emerged and its influence on our field. This course introduced us to research ethics in a very concrete and engaging way, which I really value looking back.”

[10] “Making one aware of the difficulties in scientific publishing and psychological research but also being part of a classroom where everyone would eventually face those difficulties made the topics of open science contribution more engaging and instilled a sense of not being alone in the future of tackling the problems of the replication crisis.”

Providing insight into open and non-open science practices also adds to students’ critical thinking abilities [11, 12, 13]. These skills are crucial to assess the quality of published scientific literature, for instance by considering the perspective of a replicator. Being able to determine whether a specific article is of high standard and positively contributes to advancing the scientific discipline creates a sense of trust in science. Moreover, these skills extend beyond the confines of the laboratory into real life, for instance when critically assessing other information sources.

[11] “The assessment also encouraged creative thinking about conducting replication reports, making you think of personal motivations to conduct such studies, and changing their perception of being unoriginal to something meaningful.”

[12] “Critical thinking was continually encouraged during all activities of the course. This contrast to other courses where studies would be solely discussed and summarised was a great way to start looking at research from another perspective. I will continue to use the skills I learned on how to critically analyse a study during the course.”

[13] “Analysing existing research with the goal of replication in mind was a great test for our critical thinking abilities, as well as a more practical application of our research skills. It was a new approach to practicing and improving research skills, as opposed to more traditional exercises such as verbally assessing a study or simply writing a paper for a school assignment. In my experience, it offered a new perspective on how to assess research papers and stimulated us to not only point out what was done wrong, but actively think about how could I tackle this specific problem and improve this study. This empowered me as a student and made me more confident in my research skills.”

According to students, another advantage of teaching about open science and Registered Reports is that it demystifies the scientific field, and makes science more approachable [14, 15, 16]. Drafting a Stage 1 Registered Replication Report serves as a gentle introduction to scientific methods, eliminating the pressure of designing an entire experiment or worrying about obtaining significant results while still contributing to science. Moreover, providing students with a clear, step-by-step guide on writing a Registered Replication Report instils a structured approach to scientific practices within students, making the entire process less daunting [17, 18]. As a result, after finalizing the course, many students felt more confident about their ability to conduct independent research.

[14] “Above all, the feeling that the exercise had real life importance added to the amount of joy experienced during the research process. Suddenly, I was not only a student anymore, now I got a glimpse of what it was like to be a real researcher making real change.”

[15] “Talking about such problems and being part of this small community made an actual difference for the assessment at the end of the course. With it I felt I was already contributing to scientific integrity and the future of better psychological science. The struggle of becoming part of the scientific community is something every future researcher feels when choosing this path. However, the course assessment made this goal feel more attainable. The sense of identity that it builds is strong, as conducting a Stage 1 Registered Replication Report not only makes you feel like you already belong to this open science community but also teaches you each step of the process. It creates an exciting sense of contributing to something meaningful. Open science has been previously presented as somewhat of an idealistic concept, but this hands on-experience made it real.”

[16] “The course made me feel like we, as students, were viewed as serious and valid contributors to the field.”

[17] “The course teaches not only the importance of replicating research and revising findings we have always considered a given, but it also offers a very subtle introduction into conducting research. When replicating a study which has been planned through already, it is much easier to handle when still a student, trying to step into the scientific field of psychology.”

[18] “Moreover, the process of registering a replication report makes you realize how structured and feasible research can be when carefully planned and openly registered from the start, making the seemingly unreachable goal of becoming a researcher into something attainable.”

Downsides of Registered Replication Reports

The second consensus meeting discussed the perceived downsides of introducing Registered Replication Reports in the classroom. One limitation pertains to the time it would take if students were to see the entire process through (i.e., if they not only were to provide a Stage 1 Registered Report, but were also expected to move on to the second stage). Students feared that the entire process would take too long and that they might not be able to finish their projects in time, for instance if they considered conducting a Registered Report for their master thesis. While they acknowledged that it could be a meaningful learning experience, they mentioned that it is also important to be mindful of the limited time available for learning and to use that in an efficient way. More generally, students indicated that they would have liked to have more time to draft and perfect the methods and analysis plans for their replication study. When time is limited, students might not be able to grasp all necessary information about the nature of the issue and create high-quality reports.

Related to the issue of timing, they also brought up the fact that they may be too inexperienced to draft a perfect design, method, or report on the first try. After pre-registering their projects, students might find better methodological options or encounter difficulties while conducting the planned research. Having to admit to mistakes and/or justify changes might refrain students from pre-registering their work because of the perceived loss of face and the additional time and effort required. Furthermore, if students themselves do not find mistakes or improvements, reviewers might. Addressing this might take even more time, which is not always possible within the scope of student projects.

From the course, the students also took home that Questionable Research Practices (QRPs) are a pervasive problem. For instance, they learned that in a recently published survey (Gopalakrishna et al., 2022), 51.3% of respondents admitted having engaged in QRPs (see Fanelli, 2009, for an overview of such surveys). It is noteworthy that not all of these malpractices are committed intentionally. Some researchers consider certain questionable methods standard and have even been taught to use them. Therefore, the students considered the risk of being supervised by someone who (unknowingly) contributes to the problem and might influence the students to follow their steps as quite high. To see their open science education through, they expect that all staff in their programme are well-versed in the domain of open science.

Lastly, a more practical consideration raised by the students pertained to the selection of articles provided for replication. A notable benefit of teaching students scientific methods through replication is the ability to make the material more engaging by tailoring the provided articles to students' interests. Consequently, a potential pitfall of the effectiveness of using Registered Replication Reports in the classroom could be that students lack interest in the selection of articles provided, defeating the purpose. To avert this risk, providing students with a sufficiently large catalog of articles to replicate is essential. Furthermore, during the consensus meetings, students raised concerns about the variable quality of prospective replication target articles resulting in differential workloads for students. Thus, when making article selections, it is important to set strict selection criteria to ensure that articles are sufficiently similar and that no students will be disadvantaged.

Discussion

In this paper we introduced the idea of using Registered Replication Reports in the undergraduate methods classroom. We outlined a course in which this idea was put to practice by having undergraduate psychology students compose Stage 1 Registered Reports in which they proposed to replicate a published finding. The coordinator of the course, together with volunteering students who had taken the course, reflected on the potential of using Registered Replication Reports in the classroom through a series of consensus meetings held during a Paper-in-a-Day (PiaD) workshop that led to this article. When evaluating the outcome, it is important to acknowledge that the volunteering students may not represent a fully representative sample, which should be considered when interpreting the findings.

Benefits of using Registered Replication Reports

The anticipated benefits of incorporating Registered Replication Reports in the classroom were largely realized. The structured approach provided a scaffolded learning experience, making the exercise accessible to students while reducing the risk of them becoming overwhelmed by the variety of tasks involved. By engaging in a meaningful and authentic research activity, students reported finding the task motivating and rewarding. The broader educational goals of fostering critical thinking and instilling values associated with open science, such as prioritizing methodological rigor over obtaining significant results, were also met. More specifically, students felt better prepared for a research landscape that increasingly emphasizes transparency and reproducibility.

It should be noted that these benefits are not specific to Registered Replication Reports. Pre-registering and conducting a replication are two means of providing a scaffolded learning experience, either through the specific pre-registration format that is used or by being able to rely on the methodological and analytical choices provided in the target article. In Registered Replication Reports, these two come together, making for a very accessible introduction to conducting research. Any course that introduces students to open and responsible science early in the curriculum is expected to foster critical thinking skills and to install open science values (Pownell et al., 2023a).

Challenges and barriers

One of the initial reasons for having students compose Stage 1 Registered Replication Reports was to provide them with a meaningful and comprehensive introduction to research methodology during a short course of only five weeks. The idea was that this exercise would be particularly useful when time or other logistic constraints prevented students from collecting the necessary data. Yet, students still expressed that the five-week course duration felt insufficient for producing high-quality reports, highlighting the tension between limited time and the depth of engagement required for the task. When further discussing the downsides of Registered Replication Reports in the classroom, the students took a broad perspective, investigating the possibility of making use of Registered Reports beyond the confines of the course, and considered the possibility of building entire research projects around it (e.g., bachelor or master theses). Their main concerns were that they would lack the necessary time and experience to see the entire process through. They also noted that potential supervisors must be on board regarding students’ intentions to practice open science.

Regarding the first concern: In practice, when students indicate that they want to work out their proposals for their bachelor thesis, we do not submit them as Registered Reports for peer review, but rather pre-register them on the Open Science Framework. This allows the students to practice open science, while adhering to the schedule of the curriculum. The second concern points to the broader issue of integrating open science practices within a curriculum—a single course is unlikely to achieve long-term change unless supported by a program-wide commitment to these values, for instance in a learning line that runs across several courses.

Another notable concern for students was the fear of openly pre-registering their work, which they worried might expose them to criticism or scrutiny. For students in the early stages of their academic careers, this fear of making visible mistakes can be intimidating. While pre-registering their work on platforms like the Open Science Framework can showcase their skills and commitment to open science when applying to graduate programs, there is also a risk if the quality of their early work is not sufficiently high. To mitigate this, the course coordinator retains discretion over posting reports publicly, ensuring that only work of sufficient quality is shared.

The perceived barriers in terms of time and support have previously been indicated for related open science education projects, for instance involving pre-registration (Pownall, 2020; Pownall et al., 2023b) and the use of multiverse analyses in the classroom (Heyman & Vanpaemel, 2022). Teachers considering these activities should be mindful of these challenges and take the necessary actions to mitigate any potential downsides of enthusing students about open science (see below for alternatives). Indeed, the barriers that were mentioned also indicate hidden costs of doing open science (Hostler, 2023) and the dilemma that engaging students in costly and time-consuming open science practices may cost them in the short term, for instance because they are less productive than students who do not take the time to pre-register or make their work FAIR (Heyman, 2019).

Improvements

There are several ways to address the challenges and barriers indicated above and to enhance the implementation of Registered Replication Reports in undergraduate education. For instance, the way the course was set up so far, does not allow students to benefit from the feedback opportunities Registered Reports provide. It would be straightforward to include this in the course design (if time permits) by organizing simulated peer review of a first draft of the Stage 1 manuscript. The course coordinator or fellow students could act as mock peer reviewers, providing suggestions on how to improve the Stage 1 proposal. Group assignments could further enrich the learning experience by fostering diverse perspectives and promoting collaboration, in line with principles of open and responsible research. This approach was successfully implemented during the first iteration of the course (see https://osf.io/wab9u/ for dedicated materials and rubrics).

Another straightforward change would be to allow students to select topics themselves, rather than having them choose from a list. This would probably lead to greater engagement and motivation by enabling them to develop expertise in areas of personal interest. This would impose a significant burden on the course coordinators though, who would have to acquaint themselves with different target papers to ensure eligibility, feasibility, and fairness in terms of difficulty and workload. Although the current course is tailored to quantitative research, Registered (Replication) Reports could also be adapted for qualitative research (Karhulahti et al., 2023; McAleer & Paterson, 2021).

The scope of the course could also be extended to include actual data collection. While this offers students a more complete research experience, it also introduces additional challenges such as increased time demands. Several students have successfully developed their Registered Reports into bachelor’s theses, and two student projects have gone on to be accepted as Stage 1 Registered Reports at A1 journals (Louter & Verheyen, 2024; Tuttle et al., 2023). Gilad Feldman (Feldman, 2021) has successfully implemented Registered Replication Reports in master theses at Hong Kong University, producing a staggering 120 replications and extensions of classic findings in social psychology and judgement and decision making. Information about this related project, including a host of useful resources and best-practices can be found on the dedicated website (CORE Team, 2023). It highlights the potential of educational projects to advance the field through robust replication studies—an area often overlooked by seasoned researchers.

Finally, one could also consider adopting the PiaD method in the undergraduate curriculum, for instance to conduct actual replication studies. The PiaD workshop that was dedicated to writing this paper was well received by the participating students. The workshop took place in a peaceful setting and involved formal as well as informal activities (e.g., a shared lunch). The structured yet relaxed environment fostered collaboration and creativity, which were essential to complete the challenging task of arriving at a joint paper [19, 20, 21].

[19] “This experience taught me a lot about the importance of teamwork, of discussions with others with the aim to find a middle ground.”

[20] “I learned so much about teamwork and academic writing outside a typical classroom setting. I found myself thinking about how our writing would be received by real researchers and reviewers. It led me to consider the impact of my contributions in a new way. Seeing how everyone’s different perspectives came together also taught me a lot about collaboration.”

[21] “Writing a paper in a collaborative manner added to the open science values, by offering real-time feedback from your peers and thinking about solutions to problems together. Having others evaluate your contributions made me more aware of my own practices and emphasized a focus on honesty and transparency.”

All participating students were very motivated to work towards the shared goal of finishing the paper. This was probably due to the fact that they volunteered for the project, but the fact that they got to work on a paper that would be sent out to peer review and might be published also enthused them [22, 23].

[22] “The possibility for peer review and consequently publishing was very exciting to me. It made the work feel more important and motivated me to be more critical (in a constructive manner) of myself and others.”

[23] “The working process made me feel validated in contributing something meaningful and not just writing a paper for a university assignment.”

Clear instructions and an efficient division of tasks ensured that all participants contributed meaningfully, resulting in the successful completion of the paper within a day. While students indicated that they found the prospect of potentially publishing their work daunting [24, 25], they could nevertheless contribute without fear of negative consequences, by taking up tasks they felt comfortable doing and knowing that their work would be checked by their peers.

[24] “The coordinator also encouraged us to put our work out there, which, for a lot of us is a bit daunting, but it was a good first step toward realistic scientific reporting.”

[25] “The idea of publishing something as a student was a bit intimidating at first, but it also made the work feel more important. It wasn’t just another assignment but a chance to contribute to something bigger, and that made me care more.”

Students found the experience rewarding, both for their self-esteem and for developing practical skills such as time management and task prioritization. This approach could be integrated into the undergraduate curriculum as a complementary activity to promote collaborative learning and authentic research practice. The students also clearly indicated that to facilitate the latter, promoting student authorship is recommended, seeing that it is considered both a valuable learning experience as well as a great motivator [26, 27, 28, 29, 30].

[26] “Writing a paper along with like-minded peers who share similar goals in life is a rewarding experience. The process of seeing the whole journey go through peer review and initial rejection until it gets published makes it even more rewarding, as setbacks make the sense of achievement even stronger. The process made me feel closer to the goal of becoming a researcher and feeling part of the broader scientific community.”

[27] “As someone genuinely interested in research, going through each step gave me valuable insight into what everyday work in science actually looks like, and also what to expect.”

[28] “Up until this project, the process of publishing a paper was on more of a theoretical basis. However, this brought the whole concept closer to heart, made it more tangible, and showed us a realistic side of the process. I believe this enriching practical experience will benefit many of us in our future careers.”

[29] “Now I am aware of how to expect comments to be made on my paper, teaching me how I might receive them in the future and how I could do it for other people. I’m very excited for this project to go forward. I feel very privileged that I might get to publish a paper in my bachelor. It is not usually the case that this happens to students.”

[30] “I got to experience the complexities of the publication process, from selecting appropriate journals to facing rejections, addressing reviewer feedback, and implementing revisions. It was an insightful introduction to a side of research I had only heard about before. I am genuinely grateful to have been part of this process as it gave me a clearer understanding of what it takes to bring a paper to publication and has made the prospect of future academic writing feel more approachable.”

Teachers who consider engaging students in open science practices are therefore encouraged to reflect on how they might acknowledge student contributions if their work has a chance of getting published (Merz et al., 2025). Recognizing students’ contributions is not only the open and responsible thing to do, but might end up being incredibly valuable to them, be it in terms of feeling acknowledged and competent, learning about scientific practices, instilling the values of open science, or opening doors for them.

Appendix

Table A1. List of covered topics per skills-group meeting

|

Meetings |

Topics |

|

Meeting 1: Would I lie to you? |

Introduction to the course Position in programme Assignment & suggested schedule Case studies on fraud The role of peer review The role of replication Fabrication, falsification, and questionable research practices Poor availability of research data Reliability P-hacking Retractions Reproducibility Psychological insights into the replication crisis Experimenter effects Prejudice Dishonesty Exercises |

|

Meeting 2: Going in Circles |

Research cycle Publication bias Lack of data sharing Lack of replication Statistical power P-hacking HARKing Trust in science Open Science solutions Pre-registration Registered reports Assignment & suggested schedule Exercises |

|

Meeting 3: (Effect) Size Matters |

Replication motives A priori power analysis Effect sizes Between-subjects designs Within-subjects design G*power Exercises |

Figure A1. Schematic overview of the course

Note. This figure provides a schematic overview of the course. Black describes the time frame, blue portrays general activities, and orange is related to the suggested schedule for the assignment. Before every on-campus meeting, students were asked to read preparatory literature.

References

Alister, M., Vickers-Jones, R., Sewell, D. K., & Ballard, T. (2021). How do we choose our giants? Perceptions of replicability in psychological science. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/25152459211018199

Allen, C., & Mehler, D. M. A. (2019) Open science challenges, benefits and tips in early career and beyond. PLoS Biology, 17(5): e3000246. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3000246

Anvari, F., & Lakens, D. (2018). The replicability crisis and public trust in psychological science. Comprehensive Results in Social Psychology, 3(3), 266–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/23743603.2019.1684822

Baron, I. Z., Havercroft, J., Kamola, I., Koomen, J., & Prichard, A. (2020). Flipping the academic conference, or how we wrote a peer-reviewed journal article in a day. Alternatives: Global, Local, Political, 45(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0304375419898577

Blincoe, S., & Buchert, S. (2019). Research preregistration as a teaching and learning tool in undergraduate psychology courses. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 19(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475725719875844

Bukach, C. M., Bukach, N., Reed, C. L., & Couperus, J. W. (2021). Open science as a path to education of new psychophysiologists. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 165, 76–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2021.04.001

Camerer, C. F., Dreber, A., Holzmeister, F., Ho, T. H., Huber, J., Johannesson, M., Kirchler, M., Nave, G., Nosek, B. A., Pfeiffer, T., Altmejd, A., Buttrick, N., Chan, T., Chen, Y., Forsell, E., Gampa, A., Heikensten, E., Hummer, L., Imai, T., Isaksson, S., Manfredi, D., Rose, J., Wagenmakers, E.-J., & Wu, H. (2018). Evaluating the replicability of social science experiments in Nature and Science between 2010 and 2015. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(9), 637-644. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0399-z

Center for Open Science (2019). Registered Reports: Peer review before results are known to align scientific values and practices. https://cos.io/rr/

Chambers, C. D. (2013). Registered reports: a new publishing initiative at Cortex. Cortex, 49(3), 609-610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2012.12.016

Chambers, C. D. (2019, September 10). What´s next for Registered Reports? Nature. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-02674-6

Chambers, C. D., & Tzavella, L. (2021). The past, present and future of registered reports. Nature Human Behaviour, 6(1), 29–42. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01193-7

Chopik, W. J., Bremner, R. H., Defever, A. M., & Keller, V. N. (2018). How (and whether) to teach undergraduates about the replication crisis in psychological science. Teaching of Psychology, 45(2), 158–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628318762900

Clarke, B., Lee, P. Y., Schiavone, S. R., Rhemtulla, M., & Vazire, S. (2024). The prevalence of direct replication articles in top-ranking psychology journals. American Psychologist. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0001385

Cohen, J. (1994). The earth is round (p<. 05). American Psychologist, 49(12), 997–1003. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.49.12.997

CORE Team (2023). Collaborative Open-science and meta Research (CORE) Team. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/5Z4A8

Eder, A. B., & Frings, C. (2021). Registered Report 2.0: The PCI RR Initiative. Experimental Psychology, 68(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1027/1618-3169/a000512

Fanelli, D. (2009). How many scientists fabricate and falsify research? A systematic review and meta-analysis of survey data. PLoS ONE, 4(5), e5738. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0005738

Feldman, G. (2021, November 10). Open science and science reform. Gilad Feldman. https://mgto.org/open-science/

Fink, A., Kosecoff, J., Chassin, M. R., & Brook, R. H. (1984). Consensus methods: Characteristics and guidelines for use. American Journal of Public Health, 74(9), 979–983. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.74.9.979

Frank, M. C., & Saxe, R. (2012). Teaching replication. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(6), 600-604. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612460686

Frankowski, S. (2021). Increasing participation in psychological science by using course-based research projects: Testing theory, using open-science practices, and professionally presenting research. Teaching of Psychology, 50(3), 291–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/00986283211024200

Gopalakrishna, G., ter Riet, G., Vink, G., Stoop, I., Wicherts, J. M., & Bouter, L. M. (2022). Prevalence of questionable research practices, research misconduct and their potential explanatory factors: A survey among academic researchers in The Netherlands. PLOS ONE, 17(2), e0263023. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263023

Grahe, J. E., Reifman, A., Hermann, A. D., Walker, M., Oleson, K. C., Nario-Redmond, M., & Wiebe, R. P. (2012). Harnessing the undiscovered resource of student research projects. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(6), 605–607. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612459057

Hawkins, R. X. D., Smith, E. N., Au, C., Arias, J. M., Catapano, R., Hermann, E., Keil, M., Lampinen, A., Raposo, S., Reynolds, J., Salehi, S., Salloum, J., Tan, J., & Frank, M. C. (2018). Improving the replicability of psychological science through pedagogy. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 1(1), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245917740427

Heyman, T. (2019, October 10). Perishing due to responsible research practices? Research Communities: Social Sciences. https://communities.springernature.com/posts/perishing-due-to-responsible-research-practices

Heyman, T., & Vanpaemel, W. (2022). Multiverse analyses in the classroom. Meta-Psychology, 6. https://doi.org/10.15626/mp.2020.2718

Hicks, D. J. (2023). Open science, the replication crisis, and environmental public health. Accountability in Research, 30(1), 34–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2021.1962713

Hostler, T. J. (2023). The invisible workload of open research. Journal of Trial & Error, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.36850/mr5

Hukkelhoven, C. (2022). A closer look at preregistration. OpenScience Blog, https://weblog.wur.eu/openscience/a-closer-look-at-preregistration/

Janz, N. (2016). Bringing the gold standard into the classroom: Replication in university teaching. International Studies Perspectives, 17(4), 392-407. https://doi.org/10.1111/insp.12104

Jekel, M., Fiedler, S., Torras, R. A., Mischkowski, D., Dorrough, A. R., & Glöckner, A. (2019). How to teach open science principles in the undergraduate curriculum—The Hagen cumulative science project. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 19(1), 91–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475725719868149

Kamermans, K. L., Dudda, L., Daikoku, T., & Verheyen, S. (2025). The is-ought problem in deciding what to replicate: Which motives guide current replication practices? Meta-Psychology. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/6xdy2_v2

Karhulahti, V.-M., Branney, P., Siutila, M., & Syed, M. (2023). A primer for choosing, designing and evaluating registered reports for qualitative methods. Open Research Europe, 3, 22. https://doi.org/10.12688/openreseurope.15532.2

Korbmacher, M., Azevedo, F., Pennington, C.R., Hartmann, H., Pownall, M., Schmidt, K., Elsherif, M., Breznau, N., Robertson O., Kalandadze, T., Ye, S., Baker, B. J., O`Mahony, A., Olsnes, J. O., Shaw, J. J., Gjoneska, B. Yamada, Y., Röer, J. P., Murphy, J., Alzawei, S., Grinschgl, S., Oliveira, C. M., Wingen, T., Yeung, S. K. (2023). The replication crisis has led to positive structural, procedural, and community changes. Communications Psychology, 1, 3. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44271-023-00003-2

Korkmaz, G., Buchner, M., & Verheyen, S. (2023). Student replications of the survival memory effect demonstrate the dance of the p-values. Brain and Cognition, 170, 106044. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2023.106044

Larsen, S. E., Hessinger, J. D., Larson, E. R., Melka, S. E., & Smith, H. (2024). “Paper in a day”: A model to encourage psychology collaboration and participation in research/program evaluation. Psychological Services, 21(2), 287–293. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000777

Lewis, M., Marthur, M. B., VanderWeele, T. J., & Frank, M. C. (2022). The puzzling relationship between multi-laboratory replications and meta-analyses of the published literature. Royal Society Open Science, 9211499211499. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.211499

Lin, T. Y., Cheng, H.-C., Cheng, L.-F., & Hung, T.-M. (2024). Registered report adoption in academic journals: Assessing rates in different research domains. Scientometrics, 129, 2123-2130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-023-04896-y

Louter, W. J., & Verheyen, S. (2024). A registered report of the animacy effect on source memory. Stage 1 Registered Report accepted by Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. https://osf.io/tq8ga

Makel, M. C., & Plucker, J. A. (2014). Facts are more important than novelty. Educational Researcher, 43(6), 304–316. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x14545513

Makel, M. C., Plucker, J. A., & Hegarty, B. (2012). Replications in psychology research: How often do they really occur? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(6), 537-542. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612460688

Malich, L., & Munafò, M. R. (2022). Introduction: Replication of crises - Interdisciplinary reflections on the phenomenon of the replication crisis in psychology. Review of General Psychology, 26(2), 127–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/10892680221077997

McAleer, P., & Paterson, H. M. (2021). Improving pedagogy through Registered Reports. Open Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 1(1), 12-21. https://doi.org/10.56230/osotl.13

Mehlenbacher, A. R. (2019). Registered Reports: Genre evolution and the research article. Written Communication, 36(1), 38-67. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088318804534

Merz, R., Strahmann, B., & Frank, M. (2025). Promoting student authorships: Advocating for fair acknowledgment of academic contributions. Presentation at the 7th Perspectives on Scientific Error Workshop, Bern (Switzerland), February 2025. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/W38SG

Nelson, N. C., Chung, J., Ichikawa, K., & Malik, M. M. (2021). Psychology exceptionalism and the multiple discovery of the replication crisis. Review of General Psychology, 26(2), 184–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/10892680211046508

Open Science Collaboration. (2015). Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science, 349(6251), aac4716. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac4716

Perrault, E. K. (2022). Teaching replication through replication to solve the replication “crisis.” Communication Teacher, 37(3), 220–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/17404622.2022.2123110

Perry, T., Morris, R., & Lea, R. (2022). A decade of replication study in education? A mapping review (2011–2020). Educational Research and Evaluation, 27(1–2), 12–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803611.2021.2022315

Popper, K. (2005). The logic of scientific discovery. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203994627

Pownall, M. (2020). Pre-registration in the undergraduate dissertation: A critical discussion. Psychology Teaching Review, 26(1), 71–76. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsptr.2020.26.1.71

Pownall, M., Azevedo, F., König, L. M., Slack, H. R., Evans, T. R., Flack, Z., Grinschgl, S., Elsherif, M. M., Gilligan-Lee, K. A., de Oliveira, C. M. F., Gjoneska, B., Kalandadze, T., Button, K., Ashcroft-Jones, S., Terry, J., Albayrak-Aydemir, N., Děchtěrenko, F., Alzahawi, S., Baker, B. J., … FORRT (2023a). Teaching open and reproducible scholarship: a critical review of the evidence base for current pedagogical methods and their outcomes. Royal Society Open Science, 10(5), 221255. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.221255

Pownall, M., Pennington, C. R., Norris, E., Juanchich, M., Smailes, D., Russell, S., Gooch, D., Evans, T. R., Persson, S., Mak, M. H. C., Tzavella, L., Monk, R., Gough, T., Benwell, C. S. Y., Elsherif, M., Farran, E., Gallagher-Mitchell, T., Kendrick, L. T., Bahnmueller, J., … Clark, K. (2023b). Evaluating the pedagogical effectiveness of study preregistration in the undergraduate dissertation. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 6(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/25152459231202724

Roediger III, H. L. (2012, January 31). Psychology’s woes and a partial cure: The value of replication. APS Observer, 25. https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/psychologys-woes-and-a-partial-cure-the-value-of-replication

Scheel, A. M., Schijen, M., & Lakens, D. (2021). An excess of positive results: Comparing the standard psychology literature with registered reports. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 4(2), 251524592110074. https://doi.org/10.1177/25152459211007467

Shrout, P. E., & Rodgers, J. L. (2018). Psychology, science, and knowledge construction: Broadening perspectives from the replication crisis. Annual Review of Psychology, 69(1), 487–510. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011845

Simons, D. J., Holcombe, A. O., & Spellman, B. A. (2014). An introduction to Registered Replication Reports at Perspectives on Psychological Science. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9(5), 552–555. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614543974

Soderberg, C. K., Errington, T. M., Schiavone, S. R., Bottesini, J., Thorn, F. S., Vazire, S., Esterling, K. M., & Nosek, B. A. (2021). Initial evidence of research quality of registered reports compared with the standard publishing model. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(8), 990–997. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01142-4

Stojmenovska, D., Bol, T., & Leopold, T. (2019). Teaching replication to graduate students. Teaching Sociology, 47(4), 303-313. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092055X19867996

Tuttle, T., Louter, W. J., & Verheyen, S. (2023). Does the animacy effect extend to images? A Registered Replication Report. Stage 1 Registered Report accepted by Memory. https://osf.io/st354

Wagge, J. R., Brandt, M. J., Lazarevic, L. B., Legate, N., Christopherson, C., Wiggins, B., & Grahe, J. E. (2019). Publishing research with undergraduate students via replication work: The Collaborative Replications and Education Project. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 247. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00247

Wiggins, B. J., & Christopherson, C. D. (2019). The replication crisis in psychology: An overview for theoretical and philosophical psychology. Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology, 39(4), 202–217. https://doi.org/10.1037/teo0000137

Wiliam, D. (2022). How should educational research respond to the replication “crisis” in the social sciences? Reflections on the papers in the special issue. Educational Research and Evaluation, 27(1–2), 208–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803611.2021.2022309

Wingen, T., Berkessel, J. B., & Englich, B. (2020). No replication, no trust? How low replicability influences trust in psychology. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 11(4), 454-463. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550619877412

Wiseman, R., Watt, C., & Kornbrot, D. (2019). Registered reports: An early example and analysis. PeerJ, 7, e6232. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.6232

Wodak, R., Kwon, W., & Clarke, I. (2011). Getting people on board: Discursive leadership for consensus building in team meetings. Discourse & Society, 22(5), 592–644. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926511405410